Gastric Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma: An Important Differential Diagnosis for a Rapidly Growing Gastric Subepithelial Tumor - A Case Report and Literature Review

Article information

Abstract

Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is a low-grade lymphoma with a long median survival time because of its low proliferation rate. A 75-year-old man was referred to the hospital for hematemesis. Upper endoscopy revealed a 30-mm subepithelial tumor (SET). Abdominal CT and EUS revealed a homogeneously hypoechoic lesion arising from the second layer of the stomach, without distant metastasis. Laparoscopic wedge resection was performed. On microscopic examination, the tumor showed diffuse aggregation of small lymphoid cells with abnormal architecture. Neoplastic cells showed positive reactivity for CD20 and prominent lymphoepithelial lesions were observed. The urease breath test was also conducted, with a negative result. Our final diagnosis was Helicobacter pylori-negative MALT lymphoma (Ann Arbor classification IE2), which is a rapidly growing SET pattern. This case highlights the importance of including gastric MALT lymphoma as a differential diagnosis for rapidly growing gastric SETs.

INTRODUCTION

Low-grade lymphomas are predominantly malignancies of small lymphocytes that are typically associated with long median survival periods because of their low proliferation rates [1]. Previously, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas were also known as pseudolymphomas or lymphoreticular hyperplasia because of the presence of reactive follicles, mixed inflammatory cell infiltration, slow growth, and favorable clinical prognosis [2]. Clinically, MALT may present with a wide variety of symptoms, ranging from nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, and epigastric pain to massive hemorrhage, chronic gastric bleeding with iron-deficiency anemia, and weight loss [3,4]. However, it is difficult to diagnose gastric MALT lymphoma during its early stages because many patients are asymptomatic, and symptoms may be nonspecific and overlap with those of peptic ulcer disease or gastritis. The endoscopic appearance of gastric MALT lymphomas can vary. There are three main endoscopic patterns: 1) a tumor-like appearance with a polypoid mass (exophytic type); 2) an ulceration or multiple small erosions (ulcerative type); and 3) large, nodular, and sometimes giant folds (hypertrophic type). However, these descriptions are not specific to all gastric MALT lymphomas [2,5].

Here, we report a rare case of a newly detected subepithelial tumor (SET)-like gastric MALT lymphoma that grew rapidly within 2 years. It mimics other potential malignant SETs, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) or leiomyosarcoma.

CASE REPORT

A 75-year-old man was referred to an emergency room for hematemesis experienced 1 hour before presentation. The amount of hematemesis was approximately 200 mL. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed 2 years prior as part of a medical examination. No specific lesion was observed upon examination (Fig. 1). The patient had had a cerebral infarction 3 years ago and was currently taking aspirin. The initial systolic blood pressure was 90 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure was 50 mmHg. The pulse rate was 77/min. Laboratory testing upon admission revealed a low hemoglobin level (11.2 g/dL; normal, 13~17 g/dL), normal platelet count (174/mm3; normal, 130~450/mm3), normal activated partial thromboplastin time (22.8 seconds; normal, 22.5~34.5 seconds), and normal prothrombin time (12.2 seconds; normal, 10~13.6 seconds).

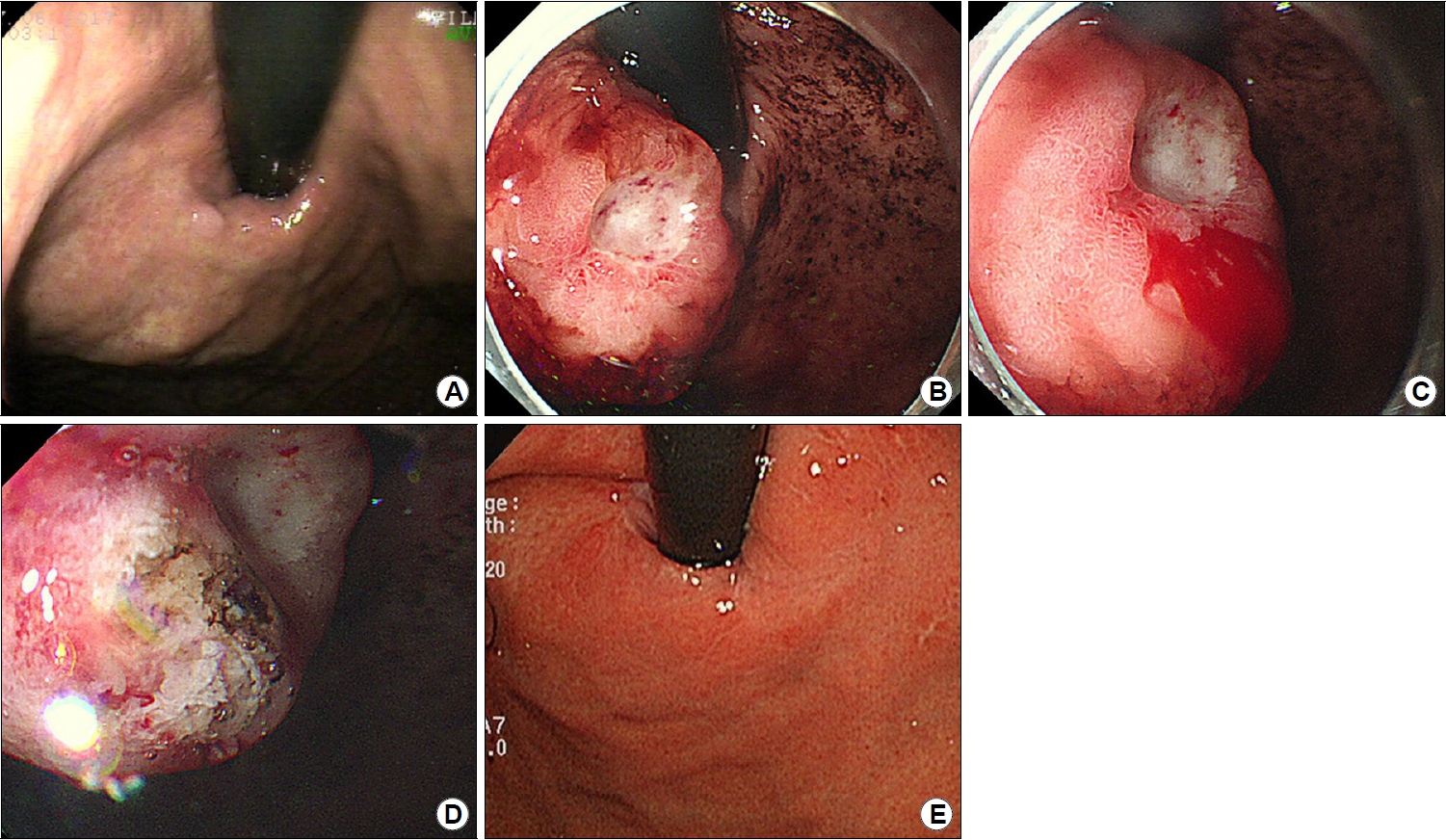

Endoscopic findings. (A) Endoscopy image taken 2 years previously showing no suspected subepithelial tumors. (B) Endoscopic findings of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (approximately 30 mm in size with central ulceration) in the gastric cardia. (C) Spontaneous bleeding from the gastric MALT lymphoma. (D) Epinephrine injection and argon plasma coagulation for endoscopic hemostasis. (E) Follow-up endoscopy image taken 6 months after the surgery showing no signs of recurrence or residual lesion.

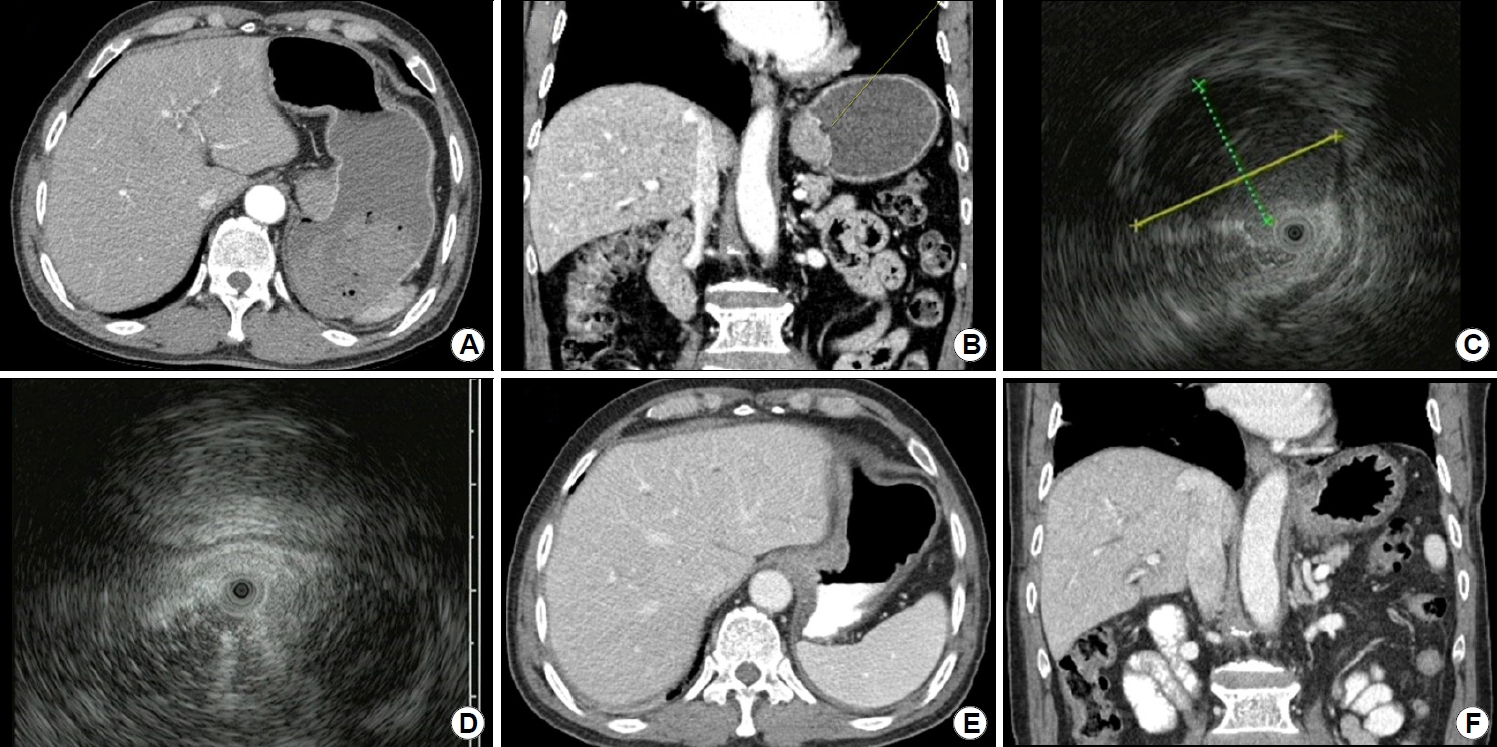

Emergency endoscopy was performed 4 hours after the arrival of the patient at the emergency room. Upon observation, a 30-mm SET was observed in the cardia of the stomach. The SET was accompanied by a protruding central ulcer. Active bleeding was observed immediately next to the ulcer site. We controlled the bleeding by injecting epinephrine and performing argon plasma coagulation (Fig. 1). After the endoscopy, abdominal and chest CT scans were performed for further evaluation. In the gastric cardia, a 27-mm enhancing mass with focal mucosal ulceration was observed. The next day, an EUS was performed, revealing a 22.8×15.9 mm sized homogenously hypoechoic SET arising from the second and third layers of the stomach wall. No surrounding lymphadenopathy was observed (Fig. 2). A biopsy was performed on the ulcer of the SET. Although a biopsy was performed in the deep part, only necrotic inflammatory tissues were obtained. After the biopsy, active oozing was observed and hemostasis was performed using epinephrine spray. Therefore, biopsy using the bite-on-bite technique was not performed.

Imaging findings. (A) A homogeneously hypodense lesion is observed in the cardia in abdominal CT transverse view. No metastasis or lymphadenopathy is evident. (B) In abdominal CT coronal view, a homogeneously hypodense lesion is seen in the cardia and a central ulcer is identified. (C, D) EUS image showing a homogeneously hypoechoic lesion measuring approximately 22.8×15.9 mm and arising from the second and third layers of the stomach wall. (E, F) Follow-up abdominal CT scan taken 6 months after the surgery showing no signs of recurrence or residual lesion.

On evaluating the results of endoscopy, EUS, and CT, our provisional diagnosis was of a stromal or mesenchymal neoplasm such as GIST or leiomyosarcoma. Therefore, the surgeon performed laparoscopic wedge resection 1 month later. Intraoperative findings were of an endophytic mass in the gastric cardia, and no other metastasis was observed. Laparoscopic resection of the mass in the posterior wall of the gastric cardia with a gross safety margin was followed by repair using a laparoscopic two-layered suture. On gross examination, the resected specimen showed a well-circumscribed solid mass measuring 25×18 mm. The cut surface was homogenously pale yellow-white and firm without necrosis. Complete tumoral resection was performed without any remnant lesions. Histologically, the tumor exhibited complete effacement of normal stomach architecture by a dense population of small lymphoid cells. Infiltration of the fourth layer by neoplastic lymphoid cells was observed. Immunohistochemical findings revealed positive reactivity for CD20 in neoplastic cells. Other immunohistochemical staining results, including CD3, CD5, cyclin D1, and Bcl-6, were negative. Immunohistochemistry of pan-cytokeratin and CD20 revealed diffuse involvement of lymphoepithelial lesions (Fig. 3). On the basis of these findings, a diagnosis of extranodal MALT lymphoma of the stomach was established. On EUS staging, it was established that the gastric MALT lymphoma was stage T3, as it affected from the second to the fourth layer [3,6]. The Ann Arbor classification of gastric MALT lymphoma was IE2 because it extended beyond the submucosal layer [2]. There was no surgical margin involvement of the tumor cells. Additionally, Giemsa staining was performed, but Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was not found. The urease breath test was performed, and the result was negative. The patient was a 75-year-old elderly man, and did not want to undergo any further evaluation except for CT or endoscopy. Therefore, neither bone marrow biopsy nor PET-CT was performed. No recurrence or residual lesion were reported during follow-up endoscopy and chest and abdominal CT performed six months after the surgery (Figs. 1, 2).

(A) Macroscopic finding of the resected gastric specimen shows pale yellow-white solid mass measuring 25×18 mm. (B) Diffuse lymphocytic proliferation is noted under the normal mucosa (H&E, ×100). (C) Immunohistochemistry of CD20 reveals diffuse infiltration of neoplastic B cells (×100). (D) CD3 is expressed on scattered reactive T cells (×100). (E) Complete effacement of normal lymph node architecture by monomorphic sheets of neoplastic lymphocytes (H&E, ×100). (F, G) Lymphoproliferative cells are positive for CD20 (F) and negative for CD3 (G) (×100). (H, I) Immunohistochemistry of pan-cytokeratin (H) and CD20 (I) highlights lymphoepithelial lesions (×100). (J, K) Low-power view shows monotonous small lymphoid cells diffusely infiltrating the submucosa and muscular layer (H&E, ×40).

DISCUSSION

The endoscopic appearance of gastric MALT lymphoma is extremely variegated, often mimicking benign diseases, such as erosions, multifocal gastritis, or other types of malignancies, such as gastric adenocarcinoma [7-9]. In rare cases, SET-like gastric MALT lymphomas have been reported (Table 1) [10-15].

GIST is the most common type of rapidly growing SETs in the stomach. GIST may appear as a submucosal mass with a normal overlying mucosa, smooth margins, and bulging into the gastric lumen. Ulceration and irregular borders are clinical malignant features of the GIST [16]. According to the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), laparoscopic wedge resection is the best treatment method. As the diagnostic accuracy and evaluation of mitoses are limited with EUS-guided fine needle tissue biopsies, the ESGE recommends laparoscopic wedge resection for GISTs with a high surgical risk, tumors located in the gastric cardia or esophagus, or unresectable GISTs [17,18].

Gastric leiomyosarcoma should also be differentiated. It is a rare disease, and symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, weight loss, bleeding, or a palpable mass [19]. Local resection with an adequate margin is the treatment of choice in the absence of invasion to adjacent structures.

In the present case, the patient visited the hospital complaining of hematemesis. Endoscopy revealed a newly developed 30-mm sized SET located in the gastric cardia with central ulceration and bleeding. EUS revealed a homogenously hypoechoic lesion arising from the second and third layers of the stomach wall. Our tentative diagnosis was stromal or mesenchymal neoplasms such as GIST or leiomyosarcoma, and laparoscopic wedge resection was performed.

Upon microscopic examination, the tumor exhibited a dense, monotonous population of small lymphoid cells and lymphoepithelial lesions. Histologic features and immunohistochemical findings led to the diagnosis of a MALT lymphoma of the stomach. MALT lymphoma cells may exhibit various cytological appearances. The most characteristic feature is the presence of small to medium-sized centrocyte-like cells with irregular nuclei. Neoplastic B cells may have a monocytoid appearance, are relatively uniform, and resemble small round lymphocytes. An important diagnostic feature of MALT lymphoma is the presence of lymphoepithelial lesions [20]. The dense diffuse infiltration of lymphoid cells into the lamina propria and epithelium can be highlighted by cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining. However, there is no specific immunohistochemical marker for MALT lymphoma. The immunophenotype of the neoplastic cells of MALT lymphoma is substantially similar to that of non-neoplastic marginal-zone B cells: CD20+, CD79a+, CD5−, CD10−, CD23−, CD43+/−, BCL6−, Cyclin D1− [21]. For the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma, the trifecta of cytologic morphology, immunophenotype, and lymphoepithelial lesion identification is required. The differential diagnosis from other small B-cell lymphomas is based on the absence of CD5 and CD10. Revealing the lack of expression of CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1 in neoplastic lymphoid cells is useful for distinguishing MALT lymphoma from follicular lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma [22].

Approximately 10% of the patients do not have H. pylori infection. Recent studies have demonstrated that eradication therapy for H. pylori is effective not only for H. pylori-positive but also for H. pylori-negative gastric MALT lymphomas. However, the response rate to H. pylori eradication H. pylori-nagative MALT lymphoma is lower than that in H. pylori-positive MALT lymphoma (75% vs. 28%) [23]. In the present case, we selected a "wait and watch" strategy after the wedge resection, but if recurrence is suspected, H. pylori eradication using antibiotics may be considered. According to the literature review, H. pylori infection was associated with about half of SET-like gastric MALT lymphomas. However, it was difficult to explain the relationship between the presence of H. pylori infection and the occurrence of SET-like gastric MALT lymphoma due to the small number of cases (Table 1).

There have been few reports of MALT lymphoma in the form of SETs, and treatment methods have not been standardized. In the present case, gastric MALT lymphoma was a round and well-circumscribed lesion, similar to an SET, so it seems that complete resection was possible with wedge resection similar to other rapidly growing SETs. Successful follow-up was reported after the removal of SET-like MALT lymphoma by endoscopic resection [10,12]. However, in those cases, the MALT lymphoma was confined to the muscularis mucosae (second layer) and submucosal layer (third layer), and endoscopic resection seemed to have been relatively easy. Although submucosal tunneling with endoscopic resection seems to be a good treatment method, lack of experience with the treatment procedure makes its effectiveness difficult to assess. It is believed that optimal treatment can be confirmed only after experience is gained in treating SET-like MALT lymphomas.

Gastric MALT lymphoma could show a rapidly growing SET pattern. Therefore, gastric MALT lymphoma should be an important differential diagnosis for a rapidly growing gastric SET.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.