급성 상부위장관 출혈 환자에서 적절한 내시경 검사 시점

Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Article information

Article: Timing of endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (N Engl J Med 2020;382:1299-1308)

요약: 급성 상부위장관 출혈 환자에서 내시경 검사는 출혈의 원인을 알 수 있게 하고, 재출혈 등 예후를 평가할 수 있으며, 활동성 출혈 병변에 대한 지혈술을 시행할 수 있다. 내원 24시간 이내에 내시경을 시행하는 경우 24시간 이후에 시행하는 것에 비해 재원 기간 및 수혈의 양, 사망률이 감소하는 것으로 알려져 있다[1]. 따라서 대부분의 가이드라인에서 비정맥류 상부위 장관 출혈 환자에서 24시간 이내에 상부위장관 내시경 검사를 권고한다[2-5]. 그러나 6~12시간 이내에 내시경을 시행하는 것은 아직 논란이 있다. 최근 홍콩에서 재출혈이나 사망 위험도가 높은 고위험 환자를 대상으로 6시간 이내에 시행한 내시경 검사의 유용성을 알아보았다[6]. 이 연구는 응급실 혹은 다른 질환으로 내과 병동에 입원한 환자 중 상부위장관 출혈의 명백한 징후(토혈이나 흑색변)가 있고 Glasgow-Blatchford score가 12점 이상인 고위험 환자를 대상으로 24시간 이내에 내시경 검사(조기내시경군)와 6시간 이내에 내시경 검사(긴급내시경군)를 비교한 단일기관, 무작위 대조군 연구이다. 조기내시경군은 자정부터 오전 8시 사이에 의뢰된 경우 당일 오전에 내시경을 시행하였으며 의뢰 후 적어도 6시간 이후에 시행하였다. 오전 8시부터 자정 이전에 의뢰된 경우 다음날 오전에 내시경을 시행하였다. 조기내시경군에 속한 환자에서 추가적인 출혈 소견(선홍색의 토혈, 혈변, 저혈압 쇼크)을 보이는 경우 바로 내시경을 시행하였다. 초기 소생술에도 불구하고 혈역학적으로 안정되지 않거나 저혈량 쇼크가 있는 경우 연구에서 제외하였다. 일차 평가변수는 무작위 배정 후 30일 이내 모든 원인의 사망이다. 이차 평가변수는 최초 내시경 시 지혈 치료 여부, 추가 출혈(지속적인 출혈 혹은 재출혈), 재원 기간 및 중환자실 입원 기간, 추가적인 내시경 치료, 응급 수술 혹은 혈관 색전술, 수혈, 무작위 배정 후 30일 이내의 우발증이다. 2012년 7월부터 2018년 10월까지 총 516명의 환자가 포함되었고, 각군에 258명씩 무작위로 배정되었다. 일차 평가변수인 30일 이내 모든 원인에 의한 사망률은 긴급내시경군에서 23명(8.9%), 조기내시경군에서 17명(6.6%)으로 양 군 간에 차이를 보이지 않았다(hazard ratio, 1.46; 95% CI, 0.72~2.54; P=0.34). 위장관 출혈에 의한 사망은 긴급내시경군에서 23명 중 5명이었고, 조기내시경군에서 17명 중 2명이었다. 이차 평가변수인 30일 이내 추가 출혈은 긴급내시경군에서 28명(10.9%), 조기내시경군에서 20명(7.8%)으로 양 군 간에 차이를 보이지 않았다(hazard ratio, 1.46; 95% CI, 0.83~2.58). 이 중 재출혈은 긴급내시경군에서 27명(10.59%), 조기내시경군에서 19명(7.4%)이었다. 최초 내시경 시 지혈 치료는 긴급내시경군에서 155명(60.1%), 조기내시경군에서 125명(48.4%)으로 긴급치료군에서 더 많이 시행하였다. 소화성 궤양이 있는 환자 중 활동성 출혈이나 혈관 노출이 보이는 경우는 긴급내시경군에서 105명(66.4%), 조기내시경군에서 76명(47.8%)으로 긴급치료군에서 더 많았다. 재원 기간 및 중환자실 입원 기간, 응급 수술 혹은 혈관 색전술 시행, 수혈의 양이나 횟수는 두 군 간에 차이를 보이지 않았다. 결론적으로 재출혈과 사망의 위험성이 높은 급성 상부위장관 출혈의 고위험 환자에서 의뢰 후 6시간 이내에 내시경 검사를 시행하더라도 30일 사망률을 감소시키지 못하였고, 오히려 고위험 병변의 발견이 많아져 내시경 지혈 치료가 증가하였다.

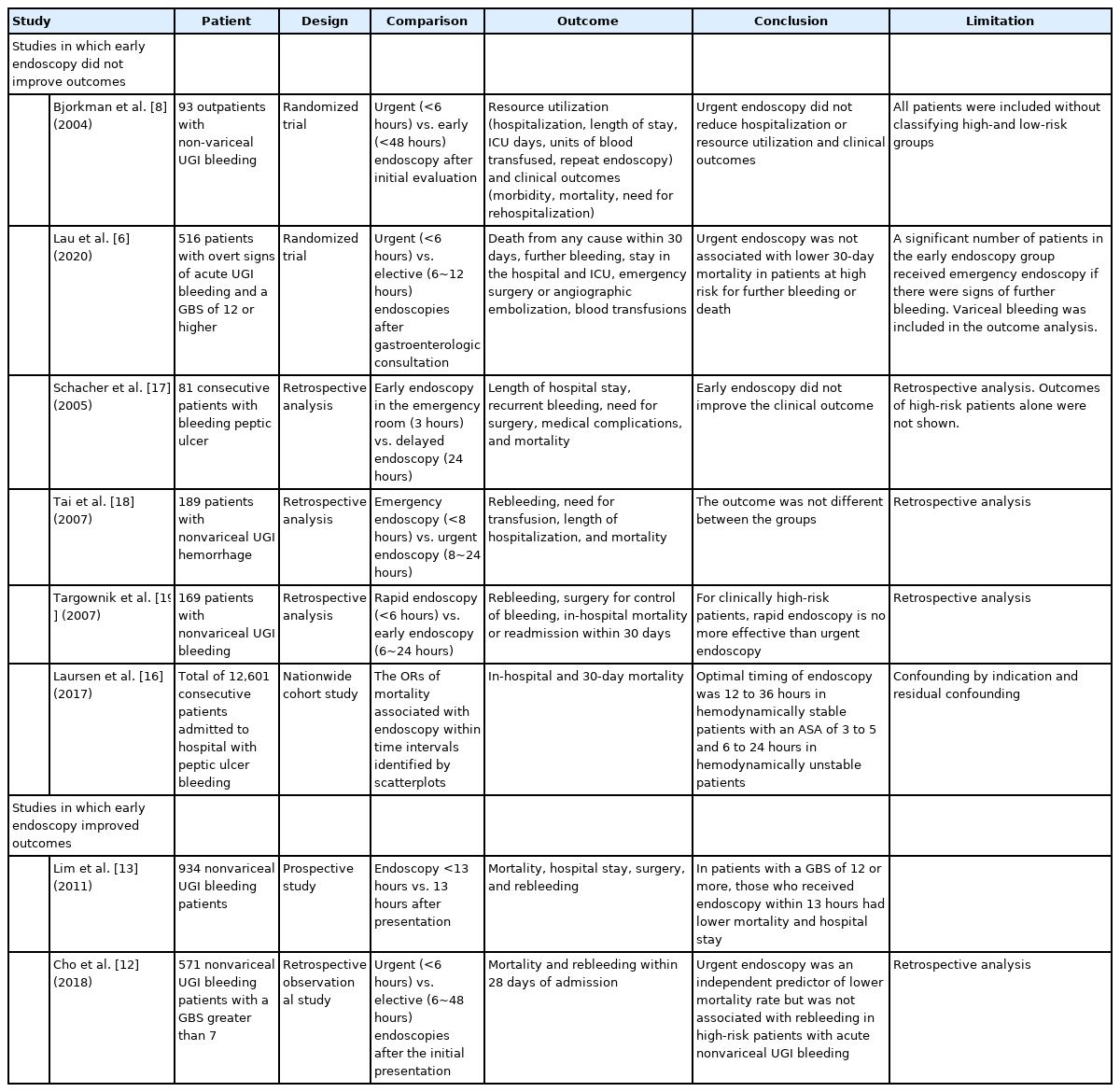

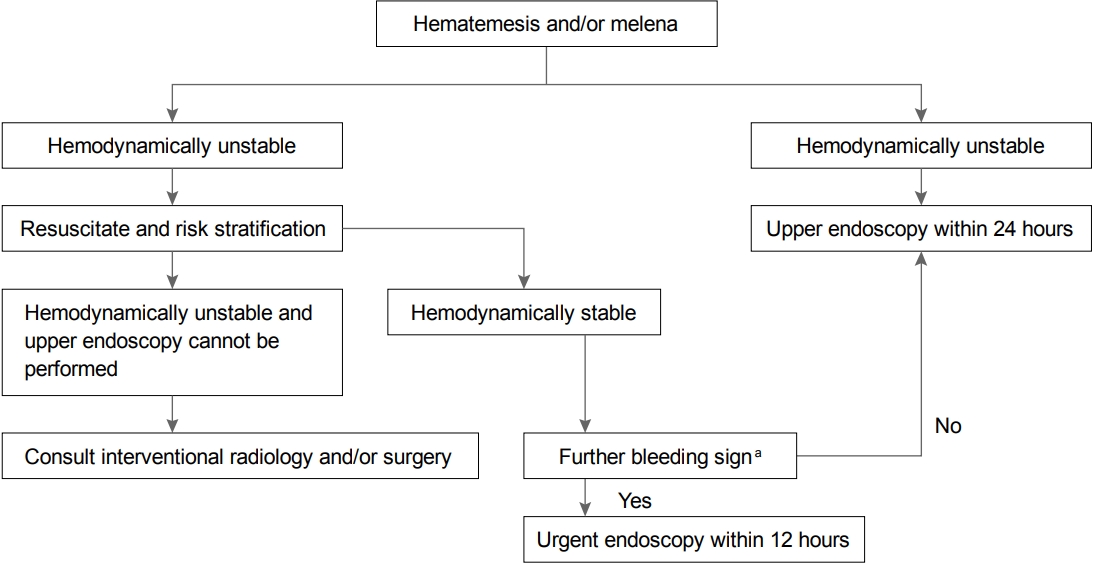

해설: 급성 상부위장관 출혈 환자에서 24시간 이내에 내시경을 시행하는 것에 대해서는 이견이 없다. 하지만 6~12시간 이내에 즉시 내시경 검사를 시행하는 것은 아직 논란이 되고 있다. 메타분석에서 12시간 이내에 내시경 검사를 시행하는 것은 재출혈과 사망률을 감소시키지 못하며 고위험 출혈 병소와 내시경 시술만 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다[7]. 무작위 대조군 연구들에서도 12시간 이내 내시경 검사가 사망률을 감소시키지 못하였다[8,9]. 그러나 상기 연구들은 위험도에 따라 환자를 분류하지 않고 모든 환자를 포함한 연구이며, 재출혈이나 사망률이 높은 고위험 환자만을 대상으로 한 결과는 보여주지 않았다. Glasgow-Blatchford score는 상부위장관 출혈 환자에서 임상적 경과를 예측할 수 있는 지표로 점수가 높을수록 내시경 시술의 필요성과 사망 위험도가 높아진다[10,11]. Glasgow-Blatchford score가 7점 이상인 고위험 환자를 대상으로 한 국내 연구에서 내시경 검사를 48시간 이내보다 6시간 이내에 시행하는 것이 의미 있는 사망률 감소를 보였다[12]. 외국 연구에서도 고위험 환자에서 12시간 이내에 시행된 내시경 검사가 사망률 감소와 연관되었다[13,14]. 이번 연구 역시 급성 상부위장관 출혈의 명백한 징후(토혈이나 흑색변)가 있고 Glasgow-Blatchford score가 12점 이상인 고위험 환자를 대상으로 하였다. 결과는 고위험 환자에서 혈역학적으로 안정되고 6시간 이내에 내시경 검사를 시행하더라도 24시간 이내에 시행된 내시경 검사에 비해 사망률이나 추가 출혈의 감소를 보이지 않았고, 통계적 차이는 없었으나 오히려 더 증가하였다. 또한 이전 연구처럼 고위험 출혈 병소의 발견이 많아져 불필요한 내시경 시술만 증가하였다. 따라서 급성 상부위장관 출혈로 내원한 환자에서 저위험 환자뿐만 아니라 고위험 환자도 혈역학적으로 안정되더라도 6시간 이내에 시행되는 내시경 검사는 환자의 예후를 향상시키지 못하며 고위험 병소의 발견만 증가시켰다. 그러나 이 연구가 잘 디자인된 연구임에도 생각해보아야 할 것이 있다. 첫째, 24시간 이내 내시경군으로 배정된 환자에서 내시경을 기다리던 중 출혈이 지속되어 2명이 사망하였다. 6시간 이내 내시경을 시행한 군에서는 내시경 검사 전 지속되는 출혈로 사망한 예는 없었다. 출혈이 지속되고 있는데도 내시경 검사를 6시간 이후로 미룬 채 환자가 사망하게 되는 경우 문제의 소지가 될 가능성이 크다. 둘째, 24시간 이내 내시경군에 배정된 환자 중에 재출의 징후가 있어 응급내시경을 시행한 경우가 20명(7.8%)이었고, 이 중 15명(5.9%)에서 24시간이 아닌 6시간 이내에 결국 내시경 검사를 받았다. 즉 24시간군으로 배정된 상당수의 환자가 6시간 이내에 내시경을 시행하였고, 이는 결과에 영향을 줄 수 있다. 또한 현성 출혈의 징후가 있는 경우 바로 응급내시경을 시행하였다는 것으로 이번 연구의 결과와 반대된다. 셋째, 상부위장관 출혈 환자에서 30일 사망률도 중요하지만 대부분 입원 후 1주일 이내 퇴원하기 때문에 초기 1주일 동안 사망률 혹은 재원 기간 중 사망률이 내시경 시점과 연관될 가능성이 크고, 이후 3주 동안의 사망률은 기저질환 등 다른 변수와 관계되어 있을 가능성이 크다. 이번 연구의 사망률 그래프를 보면 비록 유의미한 차이가 없을지라도 내원 후 10일까지의 사망률은 6시간 이내에 내시경을 시행한 군에서 오히려 더 낮아 보이고 10일 이후에 증가되었는데, 즉 재원 기간 중 사망률은 통계적 차이는 없지만 6시간 이내 내시경군에서 더 작았을 가능성이 있다. 넷째, 초기 소생술에도 불구하고 혈역학적으로 안정화되지 않았던 환자는 연구에 포함시키지 않았다. 이러한 환자들의 상당수가 정맥류 출혈의 가능성이 매우 높다. 급성 정맥류 출혈에서는 출혈 병소의 확인 및 지혈술을 위해 빠른 시간 내, 특히 내원 12시간 이내 내시경을 시행할 것을 권고하고 있고, 조기내시경 시행으로 재출혈률과 사망률을 유의하게 감소됨이 보고된다[15]. 이렇게 배제되었던 환자들에서 빠른 내시경 검사로 사망률 감소 등 예후를 향상시킬 수 있었을 것이다. 또한 비정맥류 출혈인지 정맥류 출혈인지에 따라 내시경 시간에 따른 결과가 다를 수 있음에도 이를 구분하지 않고 분석한 점은 제한점이 될 수 있다. 따라서 이러한 점들을 고려하여 이번 연구를 조심스럽게 해석해야 할 것이다. 급성 상부위장관 출혈 환자가 응급실에 내원하였을 때 혈역학적으로 안정화시키는 것이 가장 먼저 이루어져야 하며, 내시경 검사는 환자가 안정된 이후에 시행해야 한다. 12,000명을 대상으로 한 코호트 연구에서 내시경 검사 전 충분한 시간 동안 환자를 소생시키고 기저질환을 조절하는 것이 사망률 감소와 연관되었다[16]. 환자의 안정화가 가장 중요하며, 이후에 출혈이 지속되거나 재출혈이 있는 경우 환자의 상태가 불안정해질 수 있어 이러한 경우 적극적인 내시경 치료가 필요해 보인다. 최근 개정된 국내 가이드라인에서도 비정맥류 상부위장관 출혈 환자에서 24시간 이내에 상부위장관 내시경 검사를 권고하나 고위험 환자에서는 더 빨리 내시경 검사를 시행할 수 있다고 권고한다[2]. 아시아와 서구의 가이드라인에서도 혈역학적으로 불안정하거나 쇼크 상태로 내원한 고위험 환자에서는 초기 소생술과 안정화 이후 12시간 이내 내시경 검사를 시행할 것을 권고한다[3-5]. 초기 소생술에도 불구하고 환자가 혈역학적으로 불안정한 경우 비정맥류 출혈 환자에서는 경동맥 색전술(transarterial emoblization)이나 수술적 치료를 고려할 수 있으며, 정맥류 출혈이 의심되는 환자에서는 풍선 탐폰 삽입(balloon tamponade) 혹은 경경정맥 간내문맥전신 단락술(transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt)을 시행한다[2,15]. 비정맥류 출혈에서 적절한 내시경 시점에 관해 여전히 논란이 되고 있어 2000년 이후 최근 연구들을 정리해보고(Table 1), 이를 토대로 적절한 내시경 시점에 대해 저자의 견해를 제시해 보았다(Fig. 1). 이번 연구는 급성 상부위장관 출혈로 내원한 고위험 환자에서 혈역학적으로 안정되더라도 6시간 이내에 시행하는 내시경 검사는 예후와 무관하다는 결과를 보여준 연구이다. 그러나 모든 출혈 환자에서 6시간 이내에는 내시경 검사를 시행하지 않아도 된다고 오해해서는 안 된다. 초기 소생 후 현성 출혈의 징후가 없는 환자에서는 6시간 이후에 내시경 검사를 권고할만하다. 그러나 지속되는 출혈과 재출혈이 의심되는 환자(신선한 토혈 혹은 혈변, 비위관에 신선혈이 보이는 경우)에서는 정맥류의 감별 및 적절한 지혈을 위해 빠른 시간내 내시경 검사가 필요하다고 생각되며, 향후 더 많은 연구를 통한 재평가가 필요하다. 또한 원인 병소가 확인된 환자에서 지혈에 실패하거나 재출혈이 의심되는 경우 이차 추시 내시경(second-look endoscopy) 검사 시점에 따른 환자 예후에 대한 연구도 부족하여 향후 적절한 연구가 필요하다.

Clinical Trials Comparing Early vs. Delayed Endoscopy for Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Flow diagram for the timing of endoscopy in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

aIndicates either fresh hematemesis, hematochezia, bloody nasogastric aspirates, or hypotensive shock.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.