위염 Kyoto 분류의 임상적 적용

Clinical Application of the Kyoto Classification of Gastritis

Article information

Trans Abstract

Recent advances in endoscopic technology, including high-definition and image-enhanced endoscopy such as narrow-band imaging have facilitated close observation and detailed imaging of the gastric mucosa. Currently, endoscopy is performed in Korea primarily for evaluation of premalignant conditions and gastric cancer detection. Recent research has established the Kyoto classification of gastritis, a novel grading system for endoscopic gastritis, which enables prediction of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. The Kyoto classification score is calculated based on the sum of scores for five main items (of 19 endoscopic findings indicative of H. pylori infection) such as atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged gastric folds, nodularity, and diffuse redness with/without regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC). Of these five endoscopic findings, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged gastric folds, and nodularity are associated with an increased risk and RAC with a decreased risk of gastric cancer. Previous studies have reported that a Kyoto classification score ≥2 indicates current or past H. pylori infection. An increase in the Kyoto classification score is associated with a high risk of gastric cancer; specifically, a Kyoto classification score ≥4 indicates a high risk of gastric cancer. However, H. pylori eradication is followed by disappearance of enlarged gastric folds, nodularity, and diffuse redness; therefore, this grading system cannot accurately reflect the gastric cancer risk in patients with previous H. pylori infection. Limited studies have discussed the Kyoto classification of gastritis in Korea. Therefore, further large-scale multicenter studies are warranted for validation of the Kyoto classification to predict H. pylori infection and gastric cancer risk.

서 론

위암은 세계에서 다섯 번째로 많이 발생하는 암이며, 위암으로 인한 사망자 수는 네 번째로 많다[1]. 하지만 위암이 조기에 발견되는 경우는 외과적 수술 없이 내시경 점막하 박리술과 같은 내시경 절제술만으로도 완치될 수 있다[2]. 조기위암의 발견을 위해서는 정기적인 내시경 검사가, 특히 위암의 위험도가 높은 집단에서 중요하다[3]. 위암 발생의 위험인자로서 유전적 요인으로는 유전성 암 증후군(hereditary cancer syndrome), 단일염기다형성(single nucleotide polymorphism), 가족력 등이 있으며[4,5], 환경적 요인으로는 헬리코박터 파일로리(Helicobacter pylori, H. pylori) 감염, 흡연, 과도한 염분 섭취, 야채 섭취 부족 등이 있다. 이 중에서 H. pylori 감염과 위암 발병의 연관성은 잘 확립되어 있으며, cagA, vacA, iceA, dupA와 같은 H. pylori의 독력인자(virulence factor) 또한 위암의 발병과 연관이 있다[6]. 국제암연구기관(International Agency for Research on Cancer)에서는 H. pylori 감염을 제I형 발암물질로 분류하고 있으며, 실제로 H. pylori의 제균은 위암의 발생 위험도를 감소시킨다[7]. 따라서 위암을 진단하고 발병을 예방하기 위해서는 H. pylori 감염 상태를 정확하게 평가하는 것이 중요하다. 이와 같은 배경을 토대로 2013년 일본소화기내시경학회에서 H. pylori 감염 상태를 토대로 한 "위염의 Kyoto 분류"가 제창되어 사용되고 있다[8]. 또한 최근에는 고해상도 내시경의 도입으로 영상의 확대 과정 없이 위점막의 형태와 혈관 형태에 대한 자세한 관찰이 가능하게 되었다. 이에 본고에서는 현재까지 발표된 연구들을 토대로 현시점에서의 Kyoto 분류의 임상적 적용에 대해 기술하고자 한다.

본 론

1. 위염의 Kyoto 분류의 배경

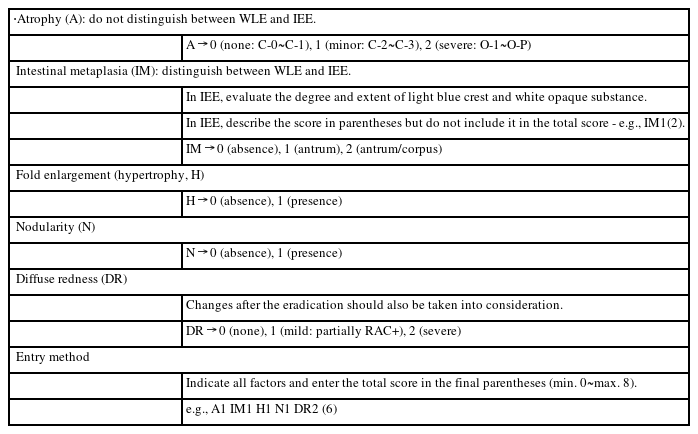

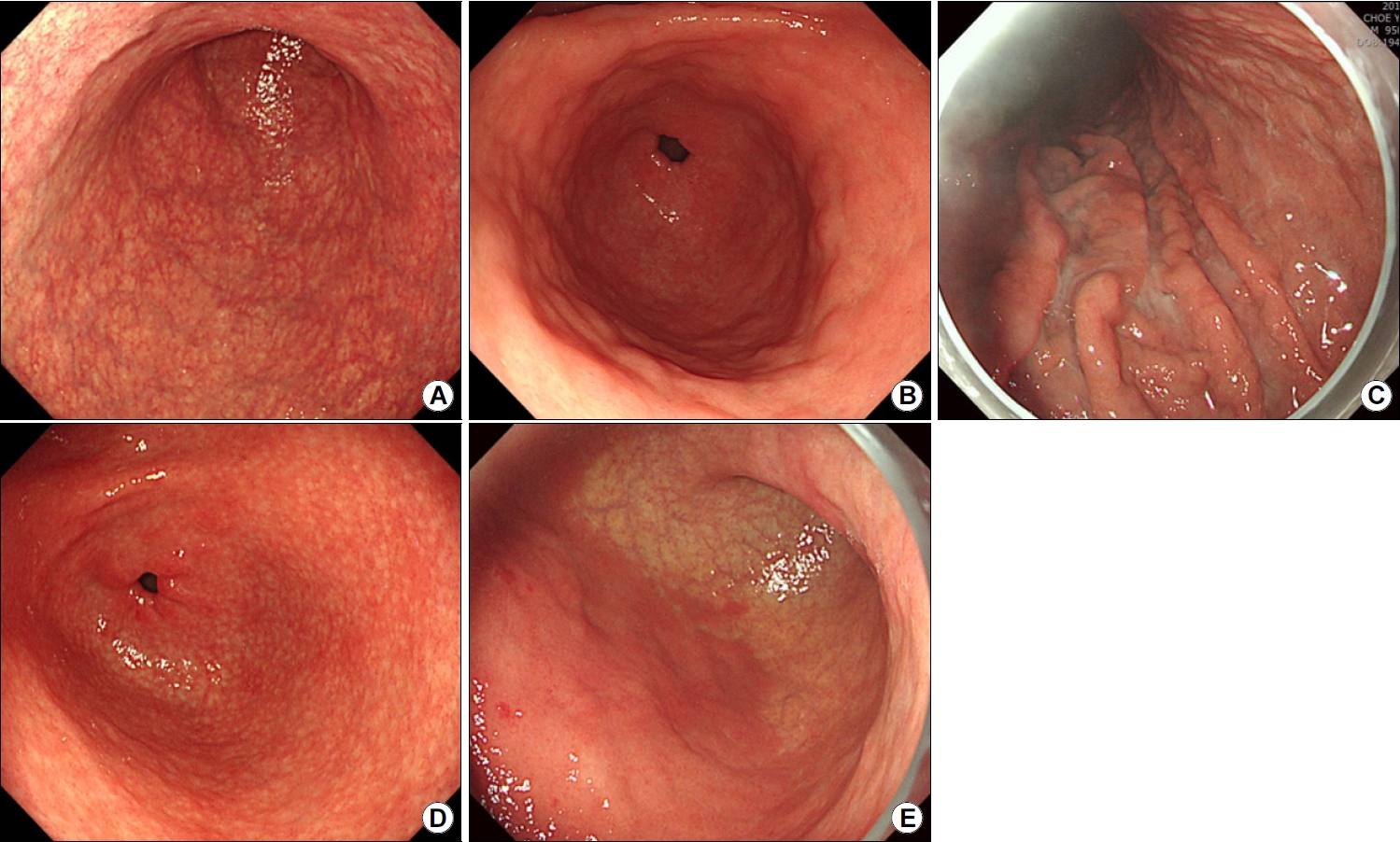

국내에서 위내시경 검사를 정기적으로 시행하는 주된 이유는 무엇일까? 당연히 국내에서 발생 빈도가 높은 위암을 조기에 발견하기 위함이다. 그렇다면 위암의 가장 중요한 원인인 H. pylori 감염으로 인한 위염을 내시경 검사 시 정확하게 진단할 수 없을까? 이러한 의문점을 토대로 2013년 일본소화기내시경학회에서 새로운 위염 분류에 관한 심도 깊은 토의 후 "위염의 Kyoto 분류"가 제창되었다[9]. 이 분류에서는 19개의 내시경 소견(집합세정맥의 규칙적 배열[regular arrangement of collecting venous, RAC], 위저선 용종[fundic gland polyp], 능선상 발적[red streak], 융기형 미란[raised erosion], 위축[atrophy], 장상피화생[intestinal metaplasia], 점막 종창[mucosal swelling], 위 체부 주름의 종대와 사행[enlarged and tortuous fold], 미만성 발적[diffuse redness], 점상 발적[spotty redness], 백탁 점액[sticky mucus], 황색종[xanthoma], 닭살 모양 결절[nodularity], 선와상피-과형성성 용종[foveolar-hyperplastic polyp], 반상발적[patchy redness], 지도상 발적[map-like redness], 다발성 백색 편평 융기[multiple white and flat elevated lesions])을 각각 H. pylori 감염 상태에 따라 분류하고 있다(Table 1). 이 중에서 위암 발생의 위험과 연관된 위축, 장상피화생, 위 체부 주름의 종대, 닭살 모양 결절, H. pylori 감염과 연관된 미만성 발적이 Kyoto 분류 점수 체계에 포함되어 있다(Table 2, Fig. 1) [9].

Representative endoscopic images of the Kyoto classification of gastritis for prediction of gastric cancer risk. (A) Atrophy. (B) Intestinal metaplasia. (C) Enlarged gastric fold. (D) Nodularity. (E) Diffuse redness.

1) 위축

위축에는 병리학적 위축과 내시경적 위축이 있다. 병리학적으로 위축은 위점막의 고유위샘의 소실로 정의된다[10]. Kyoto 분류에서는 내시경적 위축을 정의하는 Kimura-Takemoto 분류를 사용하고 있는데, 이 분류에서는 얇고 엷은 황백색의 위점막에 모세혈관망이 보이는 경우를 위축으로, 미만성 발적을 보이는 두꺼운 위점막을 비위축으로 정의하고 있다[11]. 위축은 날문부에서 시작하여 체부 소만, 전·후벽, 이후 체부 전체로 확장되므로, 범위에 따라 C-1, C-2, C-3, O-1, O-2, O-3의 6단계로 구분한다. C는 폐쇄형(closed-type)을, O는 개방형(open-type)을 의미하며, 들문부부터 날문부까지 위축이 연결되지 않은 경우를 폐쇄형, 연결된 경우를 개방형이라고 분류한다. 이러한 내시경적 위축은 병리학적 위축 및 혈청 펩시노겐 수치와 상관성이 좋은 것으로 알려져 있다[12-14]. Kyoto 분류 점수 체계에서는 비위축(C-0)과 C-1을 위축 점수 0점, C-2와 C-3을 위축 점수 1점, O-1에서 O-3을 위축 점수 2점으로 계산한다.

2) 장상피화생

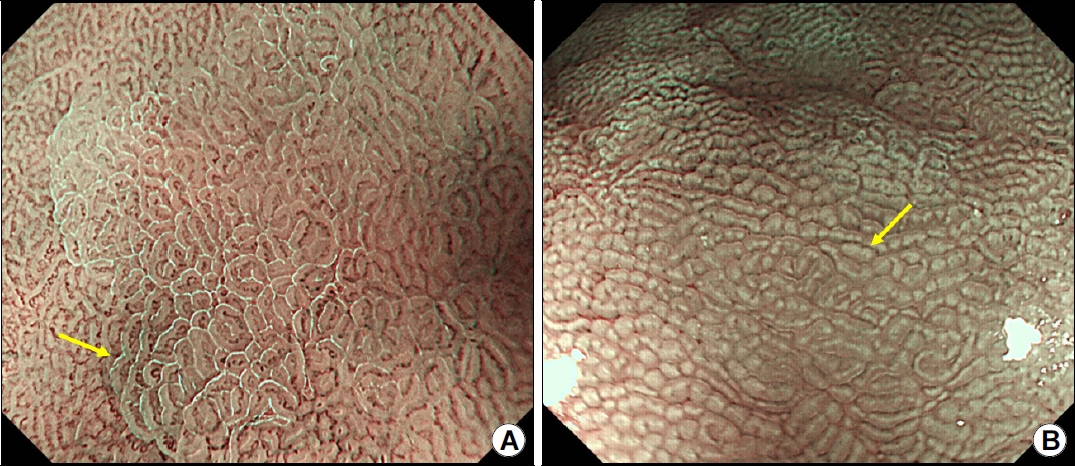

내시경 검사 시 전형적인 장상피화생은 회백색의 경한 융기를 보이는 결절성 병변이 반상의 분홍색과 퇴색 영역이 혼재된 점막으로 둘러싸여 있으며, 울퉁불퉁한 표면을 보인다. 융모성 모양(villous appearance), 백색 점막(whitish mucosa), 거친 점막 표면(rough mucosal surface)이 장상피화생의 내시경 진단에 사용되는 유용한 지표이다[15]. 협대역 내시경(narrow-band imaging, NBI)과 같은 영상 강화 내시경을 사용하면 장상피화생의 내시경 소견이 더욱 더 잘 관찰되어 장상피화생에 대한 내시경 진단의 정확도를 높일 수 있다[16]. 실제로 NBI 병용 확대 내시경 검사 시 관찰되는 위 상피 표면의 light blue crest나 white opaque substance는 장상피화생과 연관이 있다(Fig. 2) [17-19].

Findings of intestinal metaplasia on magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. (A) Light blue crest (arrow). (B) White opaque substance (arrow).

Kyoto 분류 점수 체계에서는 장상피화생이 관찰되지 않는 경우는 0점, 장상피화생이 날문부에 국한되어 있는 경우는 1점, 장상피화생이 체부까지 확장되어 있는 경우는 점수 2점으로 계산한다. 기본적으로 장상피화생은 백색광 내시경을 사용하여 진단한다. NBI와 같은 영상 강화 내시경을 토대로 한 장상피화생의 진단은 Kyoto 분류 점수 체계에 포함되어 있지 않다. 반상 발적이나 지도상 발적은 다양한 형태, 크기 및 적색을 띠는 다수의 편평 또는 경한 함몰형 발적성 병변으로 정의되며, 이러한 부위에서 조직 검사를 시행하면 대부분의 경우(87.3%)에서 장상피화생이 진단된다[20,21]. 반상 발적과 지도상 발적은 거의 유사한 소견으로 반상 발적은 비교적 크기가 작은 원형 형태의 발적이며, 이에 반해 지도상 발적은 반상 발적보다 비교적 경계가 명료하고 약간 함요되어 있는 경우가 많다. 지도상 발적이 나타나는 기전으로는 성공적인 제균 치료 후 미만성 발적이 소실되면서 위축성 점막과 비위축성 점막 사이의 색조 대비가 현저해지기 때문이라고 생각된다(Fig. 3) [22]. 제균 치료 후에 지 도상 발적이 항상 나타나는 것은 아니지만, 지도상 발적이 관찰되면 제균 후 위점막이라고 확신해도 된다[8].

3) 주름 종대

주름 종대는 충분한 공기 주입 시에 편평해지지 않거나 일부분만 펴지는 폭 5 mm 이상의 주름이 관찰되는 경우를 말한다. 주름 비후(rugal hyperplasia)는 주름 종대와 동의어이며, 소와 과형성(foveolar hyperplasia)으로 인한 점막의 두꺼워짐, 체부 점막 내 다수의 염증 세포 침윤 및 저산증(hypochlorhydria)이 흔히 동반된다[23]. 제균 후에는 대부분의 주름 종대는 소실된다[24]. Kyoto 분류 점수 체계에서는 거대 주름이 없는 경우는 0점, 관찰되는 경우는 1점으로 계산한다.

4) 닭살 모양 결절

결절성 위염(nodular gastritis)은 주로 날문부에 닭살 모양의 결절성 병변들이 다수 관찰되는 경우로 정의한다. Indigo carmine을 산포 시 이러한 결절성 병변들이 보다 더 명료하게 보인다. 내시경 생검 시 림프 여포나 현저한 단핵구 염증성 세포의 침윤이 관찰되며[25], 높은 혈청 H. pylori 항체가와 연관이 있다[26]. Kyoto 분류 점수 체계에서는 닭살 모양 결절이 없는 경우는 0점, 관찰되는 경우는 1점으로 계산한다.

5) 미만성 발적

미만성 발적은 주로 체부의 비위축성 점막에서 관찰되는 연속성의 균일한 발적을 지칭하며, 내시경 검사 시 관찰되는 표재성 위염(superficial gastritis)의 전형적인 소견이다[8]. 위점막의 염증 변화와 상피하 모세혈관총(subepithelial capillary network)의 울혈과 확장으로 인해 위점막의 색조가 발적을 띠게 된다[27]. 따라서 미만성 발적은 내시경 검사 시 발적을 평가하는 객관적 기준인 혈색소 지수(hemoglobin index)와 연관이 있다[27]. 하지만 미만성 발적의 중등도 평가는 내시경 기기와 모니터 설정에 의해 영향을 받기 때문에 객관적인 평가를 내리기가 쉽지 않다. 반면 RAC는 체부에 존재하는 집합세정맥이 관찰되는 경우이다. 원거리에서는 다수의 점처럼 보이지 만, 근거리에서 관찰 시 규칙적으로 배열한 적색의 불가사리 형태로 나타난다. Kyoto 분류 점수 체계에서는 미만성 발적이 없는 경우는 0점, 경한 미만성 발적이 있거나 일부에서 RAC가 관찰되는 미만성 발적의 경우는 1점, 심한 미만성 발적이 있거나 RAC가 소실되어 있는 미만성 발적의 경우는 2점으로 계산한다.

2. Kyoto 분류에 의한 H. pylori 감염의 진단

내시경 소견을 토대로 한 H. pylori 감염의 진단에 대해서 여러 연구에서 결과를 보고하고 있다[29-34]. 주름 종대의 경우 비교적 양호한 양측 예측도(56.2~86.0%)를 보였으며[31-33], 닭살 모양 결절은 H. pylori 감염에 대해서는 다소 낮은 민감도(6.4~32.1%)를 보이지만, 현감염에 대해서는 높은 특이도(95.8~98.8%)를 보였다[29,31,33]. 미만성 발적은 H. pylori 감염에 대해 양호한 양성 예측도(65.6~91.5%)를, RAC는 H. pylori 미감염에 대해 높은 민감도(86.7~100%)를 보여주었다[31-33]. Yoshii 등[33]은 H. pylori 기감염에 대한 내시경적 위축의 특이도는 75.5%였고, 장상피화생과 지도상 발적은 H. pylori 기감염에 대한 높은 특이도(각각 92.6%, 98.0%)를 보였음을 보고하였다. 이 중 위축과 장상피화생은 H. pylori 제균 치료 후에도 관찰되지만, 반면에 미만성 발적, 점막 종창, 주름 종대, 백탁 점액, 닭살 모양 결절은 H. pylori 제균 치료 후 호전될 수 있는 소견이다[35]. 따라서 이 5개의 내시경 소견이 H. pylori 현감염을 예측할 수 있으며, 실제로 이들 5개의 내시경 소견 중 1개 이상 있을 때 H. pylori 현감염을 예측하는 민감도는 92%, 특이도는 90%로 보고되고 있다[36].

최근에 보고된 15개 연구 4,380명을 포함하는 메타분석에서 H. pylori 미감염 진단을 위한 RAC, 위저선 용종, 능선상 발적의 민감도와 특이도는 각각 78.3% (95% CI, 66.6~86.7)와 93.8% (95% CI, 83.9~97.8), 20.4% (95% CI, 12.9~30.6)와 96.9% (95% CI, 93.4~98.5), 19.5% (95% CI, 12.6~28.9)와 95.4% (95% CI, 90.9~97.8)로, RAC가 가장 우수하였다[37]. 실제로 RAC는 관찰하기가 어렵지 않아 관찰자 간 일치도가 높아 H. pylori 감염 여부 판단에 큰 도움이 되지만[38], 초기 H. pylori 감염의 경우에는 중부 및 상부 체부에 RAC가 관찰될 수 있으므로 위각부와 하부 체부 소만에서 RAC를 평가하는 것이 중요하다[8]. 또한 H. pylori 감염이 없는 경우라도 나이가 증가함에 따라 RAC가 불명료하게 되는 경우도 있어 RAC 진단의 유용성은 50세 미만에서 더 높다고 알려져 있다[34]. 반면 H. pylori 감염 진단에 대한 민감도와 특이도는 각각 닭살 모양 결절 7.2% (95% CI, 2.4~19.3)와 99.7% (95% CI, 88.8~99.9), 점막 부종 63.7% (95% CI, 48.7~76.4)와 91.1% (95% CI, 86.9~84.1), 미만성 발적 66.5% (95% CI, 54.4~76.7)와 87.9% (95% CI, 78.5~93.5)로, 점막 부종과 미만성 발적이 H. pylori 감염 진단의 예측에 우수하였다[37]. 최근 650명의 환자를 대상으로 한 중국의 전향적 다기관 연구에서는 추가적으로 위축 영역과 비위축 영역의 경계가 불명한 경우(unclear atrophy boundary)와 RAC의 재출현이 H. pylori 기감염을 시사한다고 제시하고 있다[39].

Kyoto 분류의 관찰자 내 및 관찰자 간 일치도에 대한 연구는 많지 않은데, 77명 환자를 대상으로 한 후향적 연구에서 H. pylori 감염 진단에 대한 관찰자 내 일치도(kappa value)는 0.46~0.78, 관찰자 간 일치도는 0.62~0.82였으며, 경험이 많은 숙련자인 경우에 일치도가 더 높았다[38]. 각각의 내시경 소견에 대해 분석 시 위축과 RAC에 대한 관찰자 간 일치도가 각각 0.69, 0.63으로 가장 높았고, 황색종에 대한 관찰자 간 일치도가 0.35로 가장 낮았다. 최근 영상 강화 내시경(image-enhanced endoscopy)의 일종인 linked color imaging와 blue laser imaging을 사용한 연구에서는 각각의 내시경 소견에 대한 가시성(visibility)이 약 50% 정도 향상되었으며, 이에 따라 모든 내시경 소견에 대한 관찰자 간 일치도가 0.7 이상이었다[40]. 따라서 Kyoto 분류는 비교적 관찰자 간 일치도가 높은 분류법으로 판단된다.

또한 여러 연구에서 Kyoto 분류 점수 체계와 H. pylori 감염과의 연관성에 대해서 보고하고 있다. Kyoto 분류의 합계 점수와 혈청 H. pylori 항체 수치와의 연관성에 대한 연구에서 H. pylori 항체 수치가 음성-낮음, 음성-높음, 양성-낮음 및 양성높음인 경우에 Kyoto 분류 점수는 각각 0.1, 0.4, 1.9 및 2.3으로, Kyoto 분류 점수는 H. pylori 항체 수치에 비례하여 증가하였다[26]. 그리고 Kyoto 분류 점수 2점을 임계치로 하였을 때 H. pylori 감염을 예측할 수 있는 receiver operating characteristics curve 값은 0.886으로 우수하였다. 또 다른 연구에서도 Kyoto 분류 점수가 2 이상인 경우 H. pylori 감염을 진단할 수 있는 정확도는 90%였다.41 H. pylori 제균 치료 병력이 없는 870명을 대상으로 한 연구에서는 Kyoto 분류 점수가 0점, 1점, 2점 이상인 경우 H. pylori 감염률은 각각 1.5%, 45%, 82%였다[42]. 하지만 Kyoto 분류 점수가 높다고 해서 반드시 활동성 H. pylori 감염을 의미하는 것은 아니다. 심한 장상피화생 발생 후의 H. pylori 감염의 자연적인 소실이나 다른 감염 질환의 치료시 사용된 항생제에 의해 의도하지 않은 H. pylori 제균에 의해 위음성으로 진단되는 경우도 있다. 반면에 Kyoto 분류 점수가 0점인 경우에는 H. pylori 감염이 없음을 시사한다[43].

최근 인공지능(artificial intelligence)을 사용한 컴퓨터 보조 진단법(computer-aided diagnosis, CAD)이 다양한 소화기 질환의 진단에 사용되고 있으며, H. pylori 감염의 내시경 진단 분야에 대한 연구들도 보고되고 있다. GoogLeNet 합성곱 신경망(convolutional neural networks) 기반의 인공지능을 사용한 연구에서 CAD의 민감도와 특이도는 86.7%와 86.7%였으며[44], 또 다른 연구에서는 H. pylori 감염의 진단에 있어 CAD의 정확도는 87.7%로 일반 내시경의 정확도 82.4%보다 높았다[45]. 최근 Kyoto 분류 예측에 대한 CAD 연구도 보고되고 있는데, 498명의 환자에서 Kyoto 분류의 16개 내시경 소견의 유무를 토대로 H. pylori 감염 상태를 미감염군과 감염군으로, 이후 감염군을 현감염군과 기감염군으로 분석 시 CAD을 통한 H. pylori 감염 상태 예측의 정확도는 82.9%였다[33].

3. Kyoto 분류와 Sydney 체계와의 연관성

최근 Kyoto 분류와 개정된 Sydney 체계(updated Sydney system, USS)와의 연관성을 보고한 연구가 발표되었는데, 이 연구에서는 Kyoto 분류(위축, 장상피화생, 주름 종대, 닭살 모양 결절, 미만성 발적)와 위 체부와 날문부에서의 병리학적 USS 점수(호중구 활성도, 단핵구 침윤, 위축, 장상피화생)를 비교하였다[46]. Kyoto 분류의 5개 내시경 소견 모두 위 체부 및 날문분에서의 호중구 활성도와 단핵구 침윤에 대한 USS 점수 증가와 관련이 있었다. H. pylori 감염자를 대상으로 한 하위 분석 시 Kyoto 분류의 내시경적 위축과 장상피화생은 높은 위축과 장상피화생 USS 점수와 연관이 있었으며, 주름 종대, 닭살 모양 결절, 미만성 발적은 체부의 높은 호중구 활성도와 단핵구 침윤 USS 점수 및 전정부의 낮은 위축과 장상피화생 USS 점수와 연관이 있었다. 상기 연구의 결과를 토대로 내시경 소견을 토대로 한 Kyoto 분류는 병리학적 소견을 반영하는 분류임을 알 수 있다.

4. 위염의 Kyoto 분류 점수에 근거한 위암 발생 위험도 평가

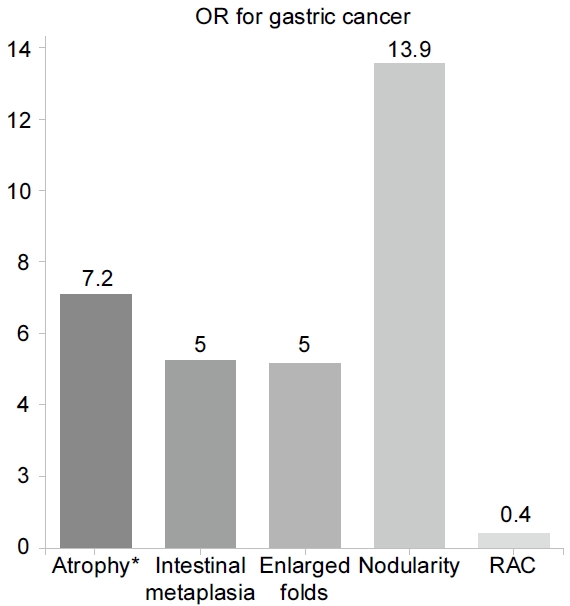

여러 연구에서 내시경 소견을 토대로 한 위암 발생 위험도 예측에 대해 보고하고 있다(Fig. 4) [47-51]. 특히 일본에서 시행된 3개의 코호트 연구에서는 내시경적 위축과 위암의 발생률과의 연관성을 보고하고 있는데, 내시경적 위축을 경도, 중등도 및 중증도로 구분 시 위암의 발생률은 연 0.04~0.10%, 0.12~0.34%, 0.31~1.60%였다[52-54]. 즉, 위암 발생의 위험도는 내시경적 위축의 정도에 따라 증가함을 보여주며, 개방형인 경우 폐쇄형에 비해 위암의 위험도가 7.2~14.2배 정도 높았다[55,56]. 내시경적 장상피화생 또한 장형(intestinal type) 위암과 관련되어 있으며[57], 내시경적 장상피화생이 관찰되는 경우 조기 위암의 위험도는 5배 정도라고 보고되고 있다[58].

H. pylori 감염군을 대조군으로 한 횡단적 단면 연구에서 5 mm 이상의 주름 종대가 있는 경우 위암의 위험도는 5배 정도였으며, 7 mm 이상인 경우는 위암의 위험도가 36배 정도까지 증가하였다[59]. 염증에 의해 매개되는 다양한 유전자의 DNA 메틸화가 주름 종대가 있는 위염에서의 위암 발생에 관여하고 있다고 보고되고 있다[60-62]. 또한 주름 종대는 미만형(diffuse type) 위암과도 연관이 있다고 알려져 있다[59,63]. 위암 환자를 대상으로 Kyoto 분류와 점막하 침윤과의 연관성을 조사한 연구도 있는데, 이 연구에서 위암 환자의 평균 Kyoto 분류 점수는 4.5점이었으며, 10 mm 이상의 주름 종대가 점막하 침윤과 연관성이 있었다.

닭살 모양 결절을 동반한 H. pylori 양성 환자에서 위암의 위험도는 13.9배였으며, 29세 미만의 H. pylori 양성 환자를 대상으로 한 연구에서는 위암의 위험도는 64.2배로 증가하였다[64,65]. 특히 닭살 모양 결절은 젊은 환자에서 발생하는 미만형 위암과 연관성이 있었다[66]. 이와 반대로 RAC가 관찰되는 경우 위암의 위험도는 0.4로 감소하였다[67].

1,200명을 대상으로 위암 발생의 고위험도를 감별하는 데 있어서 Kyoto 분류의 유용성을 평가한 연구에서도 역시 내시경적 위축과 장상피화생이 위암 발생 위험도와 연관이 있었으며, 높은 Kyoto 분류 점수가 위암 발생 고위험도군을 감별하는 데에 유용하였다[58]. 이 연구에서는 처음 발견된 위암(de novo cancer)과 이시성 위암(metachronous cancer) 발생의 위험도를 비교하였는데, 미만성 발적의 점수가 처음 발견된 위암에서 이시성 위암보다 더 높았다. Kyoto 분류 점수와 위암의 위험도에 관한 횡단적 단면 연구에서는 위암이 있는 환자와 없는 환자의 Kyoto 분류의 합계 점수는 각각 4.8과 3.8이었으며, 이 결과는 Kyoto 분류의 합계 점수가 4 이상인 경우 위암의 위험도가 증가함을 제시하고 있다[58]. 최근에 발표된 115명의 위암 환자와 265명의 대조군을 포함한 전향적 다기관 연구에서는 다변량 분석 결과 Kyoto 분류 중 개방형 위축, RAC 소실, 영상 강화 내시경에 의한 체부의 장상피화생, 지도상 발적이 위암의 고위험 소견이었으며, 이 4가지 소견을 토대로 한 변형된 Kyoto 분류가 원래의 Kyoto 분류보다 위암의 위험도 예측에 조금 더 유용함을 보여주었다(Table 3) [68].

50명의 조기 위암 환자에서 진단 2~3년 전 내시경에서의 Kyoto 분류를 대조군 50명과 비교한 연구에서는 위축, 장상피화생, 미만성 발적 및 합계 점수가 위암 환자에서 높았으며, 특히 H. pylori 제균 치료한 경우에는 위축 점수가 위암 환자에서 높았다[69]. H. pylori 제균 치료 후 발생한 위암의 개수와 Kyoto 분류의 점수에 대한 연구에서는 제균 치료 후 단일 병변이 발생한 경우의 Kyoto 분류 점수는 평균 3.8점, 다수의 병변이 발생한 경우의 Kyoto 분류 점수는 5.1점으로, Kyoto 분류 점수와 위암의 개수와의 연관성을 제시하였다[70].

하지만 대부분의 연구는 H. pylori 감염자에서의 Kyoto 분류의 전체 점수와 위암의 위험도에 대한 내용으로, H. pylori 제균 치료 후에는 미만성 발적, 닭살 모양 결절, 주름 종대가 소실되므로 H. pylori 기감염자에서는 Kyoto 분류의 전체 점수가 위암의 위험도를 정확하게 예측하는 데에는 제한점이 있다[71]. 또한 지도상 발적과 RAC의 소실이 H. pylori 제균 후의 위암 발생의 독립적인 위험인자로서 알려져 있으므로[8], 앞에서 잠시 소개된 바와 같이 위축, 장상피화생, 지도상 발적 및 RAC를 포함하는 새로운 분류 체계가 필요할 것이다.

결 론

위염의 Kyoto 분류는 H. pylori 감염과 연관된 내시경 소견을 체계적으로 정리한 분류이다. Kyoto 분류 점수가 2점 이상인 경우 H. pylori 감염이 있을 가능성이 높음을 시사하며, 이러한 경우 H. pylori 제균 과거력이 없다면 H. pylori 검사가 요구된다. 그리고 Kyoto 분류 점수가 4점 이상인 경우는 위암의 위험도가 증가되므로, 이러한 경우에는 주기적인 정기 검진과 함께 내시경 검사 시 세밀한 관찰이 요구된다. 하지만 아직까지 Kyoto 분류 점수에 대한 연구는 주로 일본에 국한되어 있어 국내에서의 추가적인 검증과 함께 국내 실정에 맞는 새로운 위염의 분류에 대한 연구도 필요할 것이다.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital in 2023.

Notes

There is no potential conflict of interest related to this work.