A형, B형, 그리고 비위축성 위염

Type A, Type B, and Non-atrophic Gastritis

Article information

Trans Abstract

The gastric cancer risk varies based on the etiology and severity of gastritis, which depends on a history of Helicobacter pylori infection and the secretory capacity of the stomach. Type A gastritis is associated with reverse atrophy of the corpus and type B with progressive atrophy extending from the antrum to the corpus. Diffuse or spotty redness in the corpus together with high serum pepsinogen (PG) II levels and a low PG I/II ratio are observed in patients with H. pylori infection when secretory capacity of the stomach is intact. Diffuse-type gastric cancer may develop near the gastric folds, which is a rare site of atrophy. Low serum PG I levels are associated with progressive gastric corpus atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in patients with chronic and previous H. pylori infections. This clinical scenario predisposes patients to intestinal-type gastric cancer, which originates in the atrophic and metaplastic gastric mucosa. Conversely, a high PG I/II ratio is observed in patients without H. pylori infection. Serum PG I levels and the PG I/II ratio are high in patients with acute H. pylori-negative gastritis, including drug-induced gastritis but are significantly low in autoimmune gastritis. Gastric neuroendocrine tumors may develop in patients with autoimmune gastritis or in those with long-term acid suppressant use. Fasting serum gastrin levels and the risk of neuroendocrine tumors are high in both cases. In this review, types of gastritis are summarized along with evaluation performed to determine the secretory capacity of the background gastric mucosa.

서 론

그동안 위염은 위축이 발생하는 A형 자가면역성 위염과 B형 헬리코박터 파일로리(Helicobacter pylori) 감염성 위염을 중심으로 다루어져 왔고, 비위축성 위염은 위암이 거의 발생하지 않는다는 가정 하에 등한시되었다[1]. 최근에 위점막 분비능을 측정할 수 있는 혈청 펩시노겐(pepsinogen, PG) 검사와 가스트린(gastrin) 검사가 널리 활용되면서 미만형 위암, 장형 위암, 신경내분비종양으로 진행하기 쉬운 위염들의 특징적인 소견들이 알려지기 시작했고, H. pylori 음성 위암도 보고되고 있다[2]. 또한, H. pylori 감염자가 줄어들면서 A형도 B형도 아닌 비위축성 위염에서 발생하는 H. pylori 음성 위염의 다양성도 알려지고 있다(Table 1).

위염은 위점막에 염증세포 침윤이 있을 때 진단하며, 위병증은 상피세포의 손상과 재생이 관찰될 때 진단한다[3]. H. pylori 음성 위염은 원인에 따라 호중구나 단핵구 침윤보다 림프구, 호산구, 육아종 침윤이 심해서 병리소견으로는 위염보다 위병증에 가까운 경우도 많다[4]. 예를 들면, 약제성 위염 중에는 염증 세포 침윤이 심해서 미란이나 궤양까지 유발하는 비스테로이드 항염증제(non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, NSAID) 연관성 위염도 있지만[5], 면역관문억제제(immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy)처럼 염증세포 침윤이 드문 약제성 위병증도 있다[6]. 하지만 조직검사소견 없이는 염증세포 침윤을 알 수 없고, 채취된 위점막이 위 전체의 병리소견을 대변하지 못하기 때문에 임상에서는 위병증도 위염으로 부른다. 담즙 자극으로 인해 발생한 위병증도 bile reflux gastropathy가 아닌 bile reflux gastritis로 부르는 것이 대표적인 예이다. 본론에서는 임상에서 볼 수 있는 위염과 위병증을 A형 위염부터 순서대로 알아본 뒤, 각각의 혈청검사 및 내시경검사 소견과 치료 및 위암 예방에 대해서 알아보기로 한다.

본 론

1. A형 위축성 위염

1) 원인

자가면역항체로 인해 벽세포와 주세포가 고갈될 정도로 파괴되어 체부 우세형 위축이 발생하는 진행성 위염이다[7]. 자가면역성 위염이 A형 위염으로 분류될 정도로 중요시되는 이유는 고가스트린혈증이 진행되면서 위에 신경내분비종양(유암종) 등의 위종양을 유발할 수 있기 때문이다[8]. 자가면역성 위염에서 발생하는 신경내분비종양은 대부분 크기가 작은 다발성 I형에 해당되므로, 다른 원인으로 인한 신경내분비종양에 비해서 전이가 드물고 예후가 양호하다[9].

A형 위염과 신경내분비종양은 B형 위염과 선암에 비해 드물어서 정확한 유병률은 알려지지 않았으나, 동양에서도 점차 증가하여 위내시경 검진을 받은 6,739명 중에서 33명(0.49%)이 자가면역성 위염으로 진단되었다는 일본 보고도 있다[10]. 자가면역성 위염은 의사가 위내시경 소견을 보고 A형 위염을 의심하여 자가면역항체를 검사하지 않는 한 진단할 수 없는 질환이므로, 체부 우세형 위축을 놓치지 않는 것이 중요하다.

2) 혈청검사소견

자가면역성 위염을 진단하는 데 도움이 되는 혈청 항체로는 항벽세포 항체(anti-parietal cell antibody)와 항내인성인자 항체(anti-intrinsic factor antibody)가 있는데, 항내인성인자 항체까지 양성인 동양인 자가면역성 위염 환자는 19.3%에 불과하여 서양인에 비해 악성 빈혈도 적다[11]. 따라서 동양인에서는 H. pylori 감염 상태와 무관하게 10 ng/mL 전후의 낮은 PG I 수치와 체부 우세형 위축성 위염이 관찰되면 자가면역성 위염을 진단하기 위해 혈청 항벽세포 항체를 검사한다[12].

본원에서 보고한 5명의 자가면역성 위염 환자들의 평균 PG I 수치는 11.4±4.8 ng/mL로 낮았으며 PG I/II 비는 1.2±0.7로 낮았다[13]. 이 중 3명은 자가면역성 갑상선염으로 치료 중이었는데, 다른 자가면역질환의 유병률이 높은 것도 자가면역성 위염을 진단하는 데 도움이 된다[14]. 나아가서 혈청 가스트린 수치가 700 pg/mL을 넘고 chromogranin A 수치가 1,000 ng/mL을 초과한 2명에서는 다발성 I형 신경내분비종양이 진단되었다. 신경내분비종양이 없는 경우, 자가면역성 위염 환자들의 혈청 가스트린 수치는 172 pg/mL를 초과하는 정도에 불과하므로, 정기적인 혈청 가스트린 추적검사는 심한 단계(florid stage)나 말기 단계(end stage)의 자가면역성 위염 환자에서 신경내분비종양이 발생할 위험성을 예측하는 데 도움이 된다[15]. 하지만 사람마다 가스트린 수치의 상승폭이 다르고 H. pylori 감염만으로도 배로 상승하기에 확진 검사로는 사용할 수 없다[16].

3) 위내시경소견

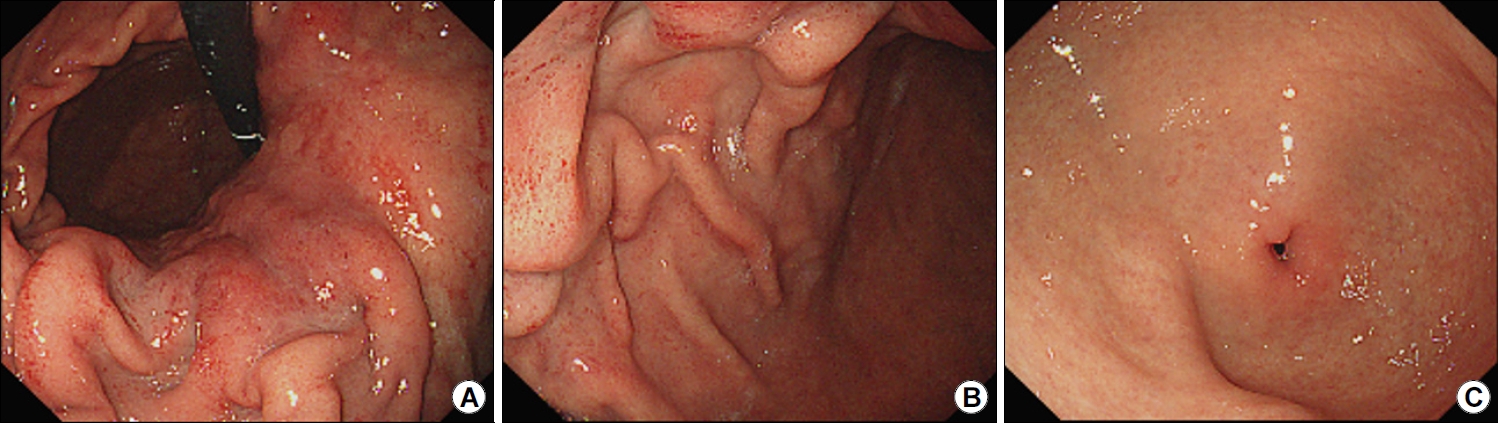

자가면역성 위염 환자의 90.1%에서 저명한 체부의 위축을 보이고 42.3%에서는 전정부 위축을 보이며 30%에서는 끈적한 흰 삼출액이 보인다[17]. 조직검사를 하면 위저선 위축, 장상피화생, 가성 유문 화생, 장크롬친화성 유사(enterochromaffin-like, ECL) 세포, G 세포 증식이 관찰된다[18]. H. pylori 감염과 동반된 경우에는 A형과 B형 위염이 혼합되어 역위축이 보이지 않다가 제균 후에야 선명해지는 경우가 있다(Fig. 1). 반대로 제균 치료 26개월 만에 호전된 자가면역성 위염 증례도 보고되었는데[19], 일부 자가면역성 위염은 T세포 매개 면역반응에 의해 발생하기 때문에 제균하면서 A형 위염까지 함께 호전된 것으로 해석된다[20].

Autoimmune gastritis diagnosed after Helicobacter pylori eradication. (A) Endoscopic image (retroflexed view) showing open-type atrophy and absence of gastric folds. (B)Diffuse redness masked by open-type pangastritis is observed in the gastric corpus. (C) A healing-stage ulcer is observed in the distal antrum. Biopsy specimen obtained from the ulcer margins showed H. pylori infection. H. pylori eradication was subsequently successful. (D) Images obtained 2 years after H. pylori eradication showing more pronounced open-type pangastritis. (E) Post-eradication image showing no diffuse redness in the corpus. (F) Image showing an old ulcer scar in the antrum but no atrophy, indicative of type A gastritis. Serum anti-parietal cell antibody test showed positive results.

4) 위염 치료 및 위암 예방

자가면역성 위염의 치료는 비타민 B12, C, D, 칼슘, 철분, 엽산, 아연, 마그네슘 결핍이 있는지 추적관찰하면서 보충하는 것이다[21]. 고가스트린혈증이 심할수록 신경내분비종양, 과형성 용종, 선와상피세포 증식으로 인한 선암 등이 발생하므로 가스트린 수치를 추적해야 한다[22]. 일반적으로 과형성 용종이 발생하면 가스트린 수치가 400 pg/mL 이상으로 높게 측정되는 경향을 보이며[23], 신경내분비종양 발생 시에는 964 pg/mL (585~1,702 pg/mL)로 보다 높게 측정된다[24].

2. B형 위축성 위염

1) 원인

H. pylori 감염이 장기화되면서 전정부에서 시작된 위축이 위각을 거쳐서 체부로 진행하는 위염을 B형 위염이라고 하며, 주로 만성 감염자나 과거 감염자에서 관찰된다. 병리 소견으로 호중구와 단핵구 침윤이 두드러지면 급성 위염, 위축과 장상피화생이 두드러지면 만성 위염으로 분류하므로, B형 위염은 만성 H. pylori 감염성 위염에 해당한다[25]. 염증세포 침윤이 사라진 부위가 섬유화되는 시기는 사람마다 달라서 급성 위염과 만성 위염을 진단하는 기준에는 기간이 포함되지 않는다. 위축은 크게 세가지 유형으로 나뉘는데, (1) 위선이 사라지면서 섬유화되는 비화생성 위축(non-metaplastic atrophy), (2) 일부 위선이 장형 모양으로 변하는 화생성 위축(metaplastic atrophy), (3) 위저선에서만 가성 장상피화생 변화를 보이는 spasmolytic peptide-expressing mucosa (SPEM) 또는 pseudo-pyloric gland metaplasia가 있다[26]. 화생성 위축이나 SPEM처럼 위축에 장상피화생이 동반될수록 선암이 발생할 위험성이 높아진다[27]. H. pylori 감염 이외에 위축을 악화시킬 수 있는 요인으로는 고령, 흡연, 고염식, 담즙 역류 등이 있다[28].

2) 혈청검사소견

위축이 심할수록 PG I 분비능이 손상되어 PG I 수치와 PG I/II 비는 낮게 측정된다[29]. H. pylori 감염이 흔한 동아시아 지역에서는 PG I 수치가 70 ng/mL 이하이면서 PG I/II 비가 3.0 이하일 때를 위암의 고위험군으로 분류하는 반면[30], 유럽에서는 PG I 수치가 30 ug/L이거나 PG I/II 비가 3 미만일 때를 고위험군으로 분류한다[31].

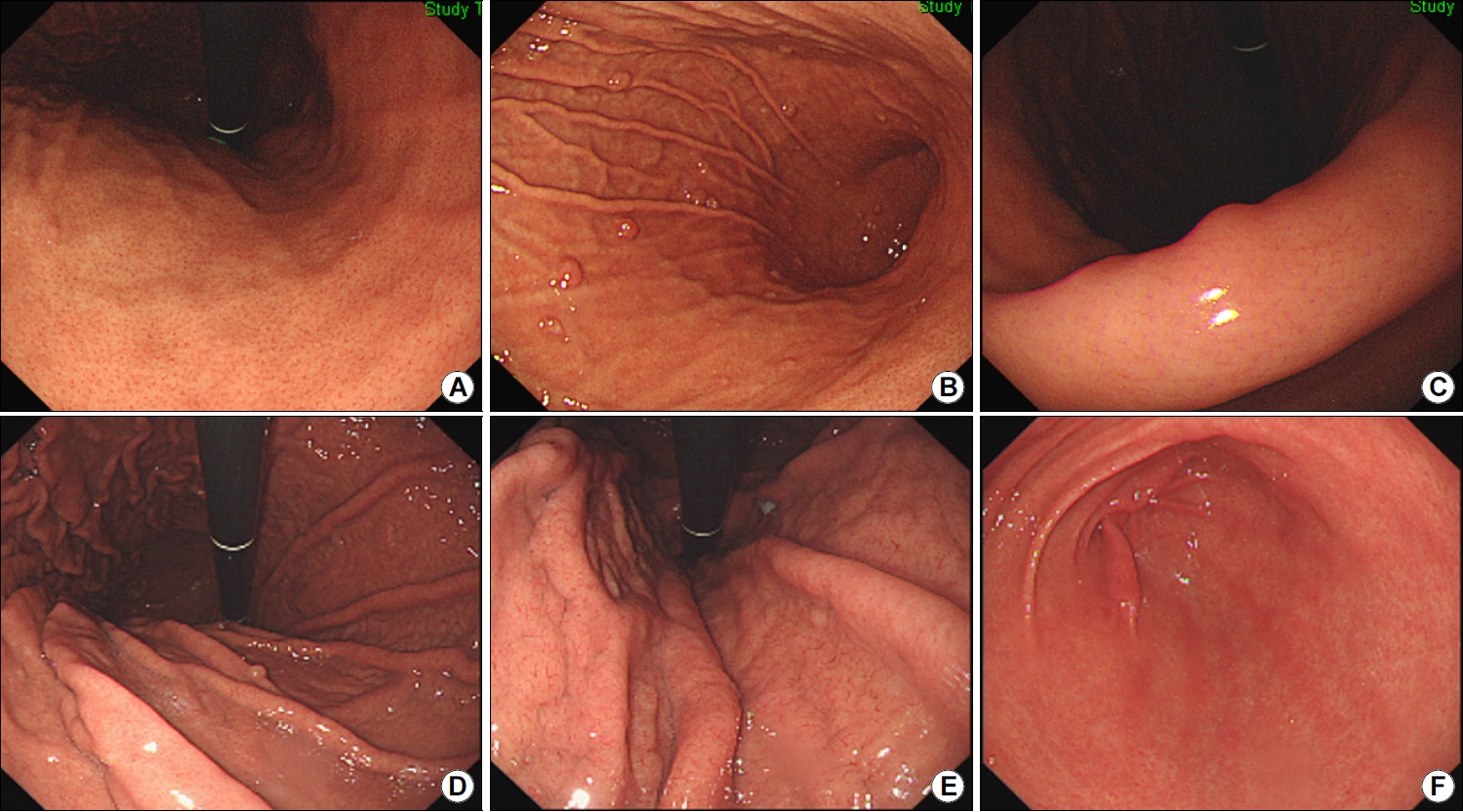

H. pylori에 감염되었으나 아직 B형 위염으로 진행하지 않은 급성 위염 단계에서는 PG I과 PG II 수치가 모두 상승한다[32]. 이러한 위점막 분비능 상승은 위축과 장상피화생이 없는 위점막일수록 현저하게 관찰되며, 위암 발생률이 높은 East Asian cagA gene을 지닌 H. pylori에 감염되었을 때 더욱 두드러진다[33]. 본원에서 무증상 한국인 500명을 조사한 결과, PG II 수치가 12.95 ng/mL를 넘고 PG I/II 비가 4.35 미만일수록 요소 호기검사에서 양성 소견을 보이는 활동성 H. pylori 감염자일 가능성이 높았다[34]. 제균에 성공하면 PG II 수치는 감소하고 PG I/II 비는 증가하면서 위내시경 소견도 호전된다[35]. 만약 제균 후에도 주름 비대가 지속되고 PG II 수치가 증가한다면 Borrmann-type IV 진행성 위암을 의심해야 한다[36]. 특히 미만형 위암은 점막하층으로 빠르게 침윤해서 예후가 불량한 위암으로 진단되는 경우가 많으므로 공기 주입 후에도 펴지지 않는 딱딱한 부위가 있는지 자세히 관찰해야 한다(Fig. 2). 미만형 위암은 위축이나 장상피화생 등의 만성 위염이 발생하지 않은 위주름 근처에서 발생하기 쉬우며, 37 한국인에서는 PG II 수치가 20 ng/mL 이상으로 높을수록 미만형 위암이 발생할 위험성이 높다[38].

Diffuse-type gastric cancer detected in a patient with Helicobacter pylori infection. (A) Endoscopic images (retroflexed view) of the cardia and upper gastric body showing hard, thick rugae. Gastric biopsy specimen obtained from the mucosa of the lesser curvature of the upper body showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and H. pylori infection. (B) Spotty redness of the gastric folds indicates active H. pylori infection. (C) No diffuse redness or cancerous changes are visualized in the antrum. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with corpus-dominant advanced gastric cancer.

3) 위내시경소견

본인도 모르는 사이에 감염되었다가 균이 사라진 경우도 있으므로 H. pylori 제균력이 없어도 위에서 위축성 위염이나 장상피화생 또는 황색종이 보이면 만성 또는 과거 감염자로 분류한다[39]. 황색종은 위축이나 장상피화생이 있는 위에서 흔히 동반되는 만성 위염 소견으로 황색종이 있는 위에서는 장형 위암이 발생할 가능성이 높다[40]. 화생성 위염은 불규칙하고 납작한 흰색 융기로 관찰되는 경우가 흔하지만 과거 감염 상태에서는 지도상 발적과 같은 함몰형 미란으로 관찰되기도 한다[41]. 위축성 위염은 분문부까지 침범한 개방형과 위축이 체부나 전정부에 국한된 폐쇄형으로 나뉘며, 위축 경계선이 위각을 넘는 폐쇄형 위축부터 장형 위암의 위험성이 상승한다[42]. 위내시경 검진 시 개방형 위축이 보이면 위암 유병률이 0.8%로 폐쇄형 위축성 위염의 0.07%보다 높다[43]. 장형 위암은 미만형 위암에 비해서 크기가 작고 위염 같은 위암으로 불릴 정도로 주변 위점막과 유사한 색과 모양을 보이는 경우가 많아서 놓치지 않도록 주의해야 한다[44].

B형 위염 환자에서 위내시경으로 조직을 채취하는 침습적인 H. pylori 검사는 위음성이 흔해서 감염자를 놓치기 쉽다[45]. B형 위염 환자의 전정부에는 균이 없는 경우가 많아서 발적이 심한 체부의 대만에서 조직을 채취해야 H. pylori 진단율이 상승한다[46]. 광범위한 발적(diffuse redness)은 H. pylori 감염으로 인해 기저부와 체부의 점막에 호중구와 단핵구가 침윤되면서 관찰되는 현상으로 위축이 없을수록 명확히 보인다[47]. 점상 발적(spotty redness)은 광범위한 발적이 심해서 다발성 혈성 반점을 형성한 것으로 역시 H. pylori 활동성 감염을 시사한다[48]. 제균 치료하면 수개월 안에 사라지고[49], 재감염 시에는 다시 관찰된다[50]. 이외에 주름 비대가 보이면 H. pylori 감염자일 가능성이 8.6배 높고, 광범위한 발적이 보이면 26.8배, 점막 부종이 보이면 13.3배, 끈적한 점액이 보이면 10.2배로 높다[51]. 한편, 결절성 위염은 닭살 모양처럼 균일한 크기의 상피하 결절들이 전정부에 밀집된 소견으로 H. pylori 감염으로 인해 림프 여포와 림프구 결집이 점막 아래로 모여서 생긴 것이다[52]. 제균하지 않으면 1~2 mm 결절들로 구성된 결절성 위염은 salt-and-pepper 모양을 거쳐 위축성 위염으로 서서히 진행하고, 3~4 mm 결절들로 구성된 결절성 위염은 화생성 위염으로 진행한다[53]. 즉, 결절성 위염은 활동성 H. pylori 감염이 지속되는 상태에서 관찰되는 위내시경 소견으로, 제균하지 않으면 위축성이나 화생성 위염으로 서서히 변한다.

4) 위염 치료 및 위암 예방

H. pylori는 위암의 가장 흔한 원인이며, 제균하지 않으면 급성에서 만성 위염으로 진행하므로 치료해야 한다[54]. B형 위염이 있는 한국인에서도 제균 후에 위축과 장상피화생은 호전될 수 있다[55]. 또한, 조기 위암을 절제받은 한국인에서도 감염이 없는 상태에서는 위내시경 검사를 1년 간격으로 자주 해도 2년 간격으로 검사했을 때와 위암 발견율에는 차이가 없다[56]. 따라서 위암의 일차 예방인 제균 치료를 먼저 한 뒤, 과거 감염 상태가 되면 이차 예방책으로 정기적인 위내시경 검사를 하는 것이 이상적이다. 제균 치료 후에 혈청검사와 위내시경 소견이 회복된 경우에는 위암 발생률이 낮아서 서양에서는 Operative Link for Gastritis Assessment나 Operative Link for Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment에서 II~IV 단계로 위축과 장상피화생이 심한 과거 감염자에게만 정기적인 위내시경 검진을 권한다[57].

3. 비위축성 위염

1) 원인

위축으로 진행하지 않는 non-A, non-B 위염의 원인으로는 담즙, 스트레스, 방사선, 술, 약, H. pylori 균 이외의 다른 미생물에 의한 감염, 위장관을 침범하는 전신질환 등이 있다(Table 1). 복합적인 원인에 의해서 발생하거나 위염의 주원인을 찾기 어려운 경우도 많아서 림프구, 육아종, 호산구, 콜라겐 침윤 등의 조직검사소견이 H. pylori 음성 위염의 원인을 진단하는 데 중요한 단서가 된다[58].

2) 혈청검사소견

H. pylori 감염성 위염과 달리 위염이 심할수록 혈청 PG I 수치와 PG I/II 비가 상승한다(Fig. 3). PG I 수치가 상승하는 H. pylori 음성 위염의 대부분은 약제성 위염이지만, 스트레스성 위염에서도 PG I 수치는 상승한다[59]. 아스피린으로 인한 위염 발생 시 PG I 수치가 123 ng/mL를 넘는 경향을 보이며[60], 골다공증 치료제인 amino bisphosphonate로 인한 위염 환자들의 평균 PG I 수치는 103.4±49.2 ng/mL로 위염이 발생하지 않은 환자들의 46.8±27.7 ng/mL에 비해 유의하게 높았다[61].

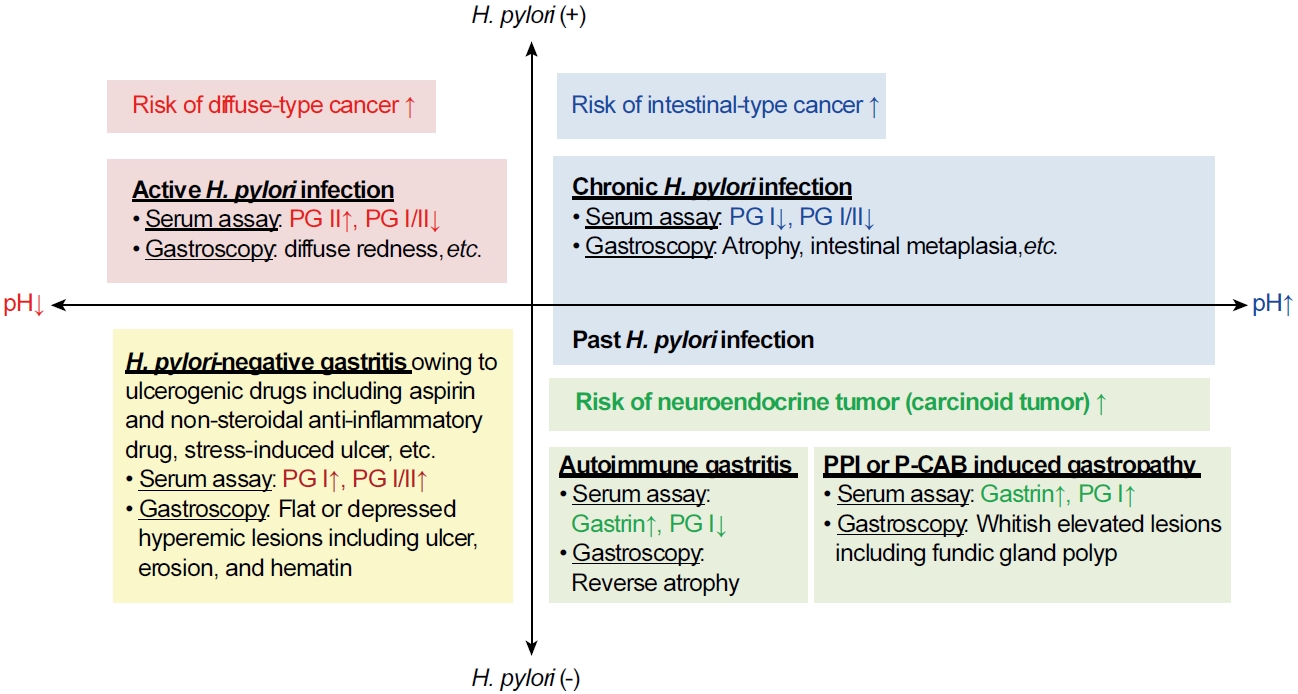

Classification of gastritis based on Helicobacter pylori infection and intragastric acidity. H. pylori infection results in increased gastric secretory capacity in patients with non-atrophic gastritis. Serum assays and gastroscopy show high PG II levels and diffuse redness in the corpus (red boxes). These changes favor development of diffuse-type gastric cancer. Progressive atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in the gastric corpus lead to decreased gastric secretory capacity; therefore, PG I levels and the PG I/II ratio are low in patients with chronic or previous H. pylori infection (blue boxes). These changes predispose patients to intestinal-type gastric cancer. Ulcerogenic drugs and stress may produce hyperemic erosions, ulcers, and hematins in the stomach (yellow boxes). The elevated serum PG I levels and the PG I/II ratios are not associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer in H. pylori-negative gastritis patients with hyperchlorhydria. Conversely, patients with H. pylori-negative hypochlorhydria show an increased risk of neuroendocrine tumor formation associated with aggravation of hypergastrinemia (green boxes). PG I levels are extremely low in patients with autoimmune gastritis but are significantly elevated after long-term acid suppressant use. PG, pepsinogen; PPI, potassium-competitive acid blocker; P-CAB, potassium-competitive acid blocker.

한편, 벽세포를 억제하는 proton pump inhibitor (PPI)나 potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB)를 수개월 이상 복용하면 ECL 세포에서는 chromogranin A, 주세포에서는 PG, G세포에서는 가스트린이 각각 과도하게 분비된다[62]. 고가스트린혈증은 복용 기간이 길수록 심하며, 여성이 남성보다 심하다[63]. 여성에서 고가스트린혈증이 심한 이유는 체중이나 체표면적에 비해서 높은 PPI 용량이 투여되기 때문이다[64]. 고가스트린 혈증이 심할수록 유암종, 과형성 용종, 선와상피세포 증식으로 인한 위선암 등이 발생하기 쉽다[65].

3) 위내시경소견

PPI나 P-CAB 장기 복용으로 인한 고가스트린혈증은 선와상피 증식과 벽세포 돌출, 위저선 확장을 유발하여 위저선 용종, 조약돌 모양의 점막, 다발성 흰색 융기형 병변, 과형성 용종 등을 형성한다[66]. PPI 장기 복용 시 조약돌 모양의 점막 발생률은 16.8배 증가하며 P-CAB 복용 시에는 12.7배 증가한다[67]. 같은 연구에서 과형성 용종 발생률은 PPI 복용 시에는 15.9배, P-CAB 복용 시에는 10.7배로 상승했으며, 위저선 용종 발생률은 PPI 복용 시에 5.9배 상승했는데, 모두 융기형 병변이라는 공통점을 보인다. 위저선 용종은 H. pylori 감염이 없을수록 호발하며 조약돌 모양의 점막은 과거 감염자에서 호발한다(Fig. 4).

Endoscopic findings following long-term acid suppressant therapy. (A) Endoscopic images of the corpus (retroflexed view) showing a regular arrangement of collecting venules. The patient denied a history of Helicobacter pylori infection and was prescribed 12-month proton-pump inhibitor therapy by the Rheumatology Department. (B) Image showing multiple tiny fundic gland polyps scattered throughout the corpus. (C) Image showing regular arrangement of collecting venules when viewed from the angle obtained in this image, indicative of a H. pylori-naive stomach. (D) Retroflexed view of the corpus showing a cobblestone appearance of the mucosa, accompanied by a fundic gland polyp. The patient had a history of successful H. pylori eradication 3 years prior to presentation, before initiation of proton-pump inhibitor therapy prescribed by the Department of Rheumatology. (E) The cobblestone appearance of the mucosa is observed up to the cardia. (F) Linear streaks are observed in the antrum without any evidence of re-infection.

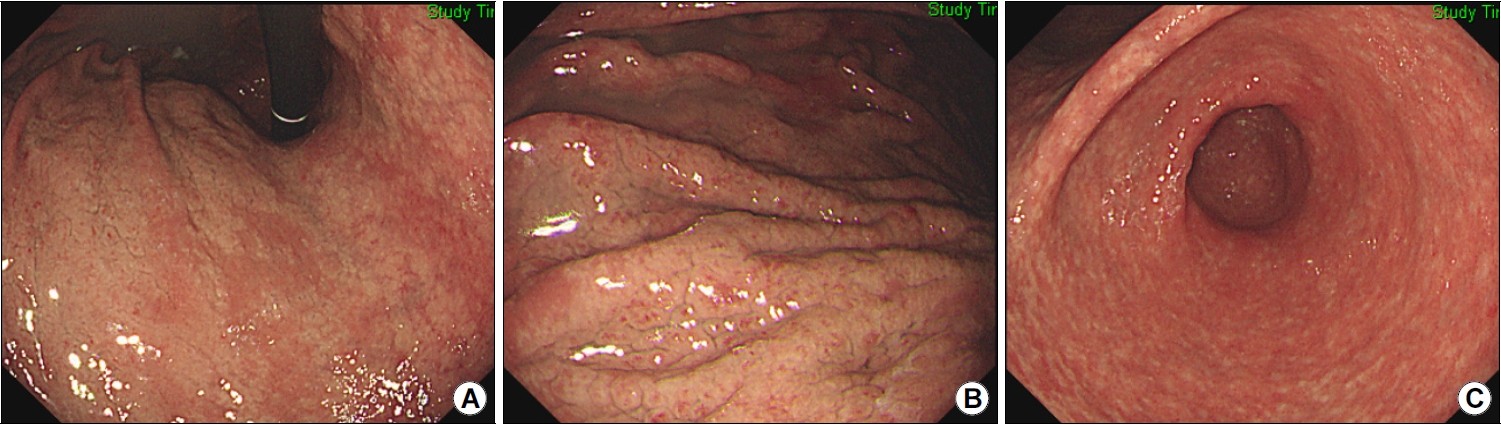

위산 분비능이 손상되지 않은 위점막에서 발생한 H. pylori 음성 위염은 미란, 궤양, 헤마틴, 선상 발적과 같은 붉은색 병변을 보인다[68]. H. pylori 감염으로 인한 손상은 위각이나 소만에서 호발하지만 약물로 인한 손상은 위 전체에 동시다발적으로 발생한다. 아스피린(acetylsalicylic acid), NSAID, tetracycline계 항생제인 doxycycline, 선택적 세로토닌 재흡수 억제제(selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), 염화 칼륨, 생물학제 등은 궤양이나 미란과 함께 호중구 및 호산구 침윤을 유발할 수 있는 약물이다[69]. 이 중에서 doxycycline은 괴사를 동반하기 쉽고, 면역관문억제제는 림프구 침윤과 세포사멸(apoptosis)를 동반하기 쉽다. 호산구, 림프구, 육아종 등의 병리소견으로 원인을 감별해야 하는 경우도 많은데, 호산구 위염은 주로 알레르기 환자에서 진단된다[70]. H. pylori 감염 시에 보이는 광범위한 발적을 동반한 주름 비대와 달리, 호산구 위염에서는 발적이 없는 점막부종이 위 전체에서 관찰된다(Fig. 5). 하지만 H. pylori 감염이 동반되거나 결절 또는 미란 등이 보이는 호산구 위염도 있으므로, 위내시경 소견만으로는 확진할 수 없으며 조직검사에서 호산구가 high per field당 30개 넘게 관찰되면 진단한다[71]. 호산구 위염은 식도염과 달리 말초혈액검사에서 호산구 증가증이 흔히 동반되므로 진단하는 데 도움이 된다[72].

Eosinophilic gastritis diagnosed in a patient with allergic rhinitis. (A) Whitish nodular appearance of the mucosa is observed throughout the gastric corpus. (B) Image showing thick edematous gastric folds. Biopsy specimen showing heavy eosinophilic infiltration. Blood tests revealed peripheral eosinophilia (white blood cell differential count: 24% eosinophils). (C) Image showed whitish nodules scattered throughout the antrum without any evidence of Helicobacter pylori infection.

4) 위염 치료 및 위암 예방

치료는 원인 물질을 차단하거나 원인 질환을 치료하는 것이다. 호산구 위염의 경우, 6주간의 제한식이요법을 통해서 콩, 밀, 계란, 우유, 땅콩, 생선과 갑각류를 금한다[73]. 호산구 위장관염으로 인해 설사, 복통, 구토, 폐색, 복수가 있으면 2주간 스테로이드를 처방한 뒤, 2주에 걸쳐 감량해서 끊거나 Th2 면역반응을 억제하는 면역치료를 고려한다[74]. 미국 대규모 연구에 의하면 H. pylori 감염자일수록 호산구 식도염의 유병률이 낮으므로[75], 위암 발생률도 낮을 것으로 추정된다.

급성 H. pylori 음성 위염이 위암을 유발한다는 증거는 없으 , PPI와 P-CAB 장기 복용으로 인해 고가스트린혈증이 심해지면 위에서 신경내분비종양이 발생할 수 있다[76]. 따라서 고가스트린혈증이 관찰되면 위산억제제를 히스타민2 차단제로 바꾸거나[77], 병용해서 PPI와 P-CAB를 감량한다[78]. 고가스트린혈증을 줄이기 위해서 muscarinic receptor antagonist를 투여하는 방법도 있다[79].

결 론

위염이 위암으로 진행할 위험성은 H. pylori 감염력과 위점막 분비능에 의해 좌우되므로, 혈청검사와 위내시경소견으로 위염을 감별할 수 있어야 한다(Fig. 6). 만약 PG I/II 비가 낮거나 계속 감소한다면 A형 위염인지 B형 위염인지를 감별해야 한다. 위내시경 검사에서 역위축을 보이면 A형 위염일 가능성이 높으므로 자가면역항체를 검사하고, 전정부에서 체부로 진행하는 B형 위축을 보이면 H. pylori가 사라진 과거 감염자라는 것을 확인한 후에 정기적인 위내시경 검진을 한다. 만성 감염자라면 제균 치료 후에 검진을 권한다. 만약 PG II가 높거나 상승 중이라면 현감염자일 가능성이 높다. 반대로 PG I/II 비가 높고, PG I 수치가 높거나 상승 중이라면 약제성 위염을 포함한 H. pylori 음성 위염을 감별해야 한다. 위산 분비가 많은 H. pylori 음성 위염은 다발성 미란이나 궤양, 헤마틴과 같은 붉은 병변을 보이는 반면, PPI나 P-CAB 장기 복용으로 인해 위산 분비가 적은 H. pylori 음성 위염은 위염은 위저선 용종, 과형성 용종, 조약돌 모양 점막과 같은 융기형 병변을 보인다. 이와 같이 각 위염의 검사소견이 다르므로, 위염을 제대로 치료하고 위암을 예방하기 위해서는 혈청검사와 위내시경소견을 보고 A형과 B형 위염뿐만 아니라 비위축성 위염을 감별할 수 있어야 한다.

Algorithms for diagnosis of gastritis based on the serum pepsinogen I/II ratio and pepsinogen I and II levels. Autoimmune antibody testing is warranted to exclude type A gastritis in patients with extremely low serum PG I levels and the PG I/II ratio. Active Helicobacter pylori infection should be ruled out in patients with increased serum PG II levels and decreased PG I/II ratios. Furthermore, chronic or previous H. pylori infection indicative of type B gastritis should be suspected in patients with decreases in both serum PG 1 levels and the PG I/II ratios during follow-up. Conversely, H. pylori-negative gastritis should be considered in patients with elevated serum PG I levels and the PG I/II ratios. Ulcerogenic drugs often produce flat or depressed hyperemic lesions throughout the stomach in the setting of non-atrophic (non-A, non-B) gastritis, in contrast to whitish elevated lesions observed in the corpus in patients who receive acid suppressant therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1D1A1B02008937).

Notes

There is no potential conflict of interest related to this work.