위축성 위염과 장상피화생의 내시경 진단 및 분류

Endoscopic Diagnosis and Classification of Atrophic Gastritis and Intestinal Metaplasia

Article information

Trans Abstract

Gastritis is the term used to describe the inflammatory condition of the stomach. However, the ambiguous application of this term in clinical practice, such as in endoscopic or histological diagnosis, makes its diagnosis and treatment unclear. Atrophic gastritis is the most common finding in screening endoscopy, especially in patients with high risk of gastric adenocarcinoma; thus, definite diagnosis of the premalignant condition is important. Several classification systems and associated terminologies have been used to define the inflammatory condition of the stomach. However, many of them are based on histological findings, and their clinical application is limited in endoscopic diagnosis. Recently, with the advancement of endoscopic imaging techniques such as narrow-band imaging, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia can now be defined more precisely. Currently, many attempts have been made to classify the condition of the stomach on the basis of endoscopic findings, focusing on the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and the presence of Helicobacter pylori.

서 론

‘위염’이라는 진단명은 임상에서 흔하게 사용되고, 심지어 환자들이 스스로를 위염이라고 표현하기도 한다. 그러나 위염이라는 진단명은 모호한 표현이다. 임상의가 붙이는 위염이라는 진단명은 증상을 기반으로 하는 경우가 많고, 내시경 검사 후 소견을 위염이라고 기술하기도 하며, 병리 진단으로 위염이라는 단어를 사용하기도 한다. 이로 인하여 위염의 진단과 치료에 혼선을 느끼는 경우가 많은 것이 사실이다.

최근 검진으로 내시경 검사를 받는 사람들이 늘어나면서 위염, 특히 위축성 위염 및 장상피화생이라는 진단명을 받게 되는 환자들도 많아지고 있다. 위축성 위염과 장상피화생은 헬리코박터 감염에 의한 염증성 변화로 위암의 발생과 상관성이 있다[1]. 많은 환자들이 미래의 위암 발생에 대한 걱정으로 진료실을 찾게 되며, 이로 인한 잦은 검사로 의료비의 상승을 야기하게 된다. 따라서 정확한 진단이 무엇보다 중요하다고 할 수 있다. 본고에서는 위축성 위염과 장상피화생의 내시경 진단과 분류에 대하여 알아보고, 그 임상적 의미에 대하여 생각해보고자 한다.

본 론

1. 위염 분류의 역사와 배경

내시경 검사 후 진단명으로 기술되는 위염이라는 단어는 위장 점막 조직의 염증을 가리키는 것으로 급성 위염과 만성 위염으로 나뉜다. 1936년 Schindler에 의하여 제창된 이 개념은 만성 위염을 다시 표재성 위염, 위축성 위염, 비후성 위염 등으로 분류하고 있다. 이후 내시경의 발전과 더불어서 Correa [2] 및 Whitehead 등[3]의 여러 연구자들에 의하여 다양한 분류가 제안되었으나 이는 조직학적 소견에 초점을 둔 분류였다. 1980년대 헬리코박터와 위염의 연관성이 밝혀진 이후 연구가 활발해지면서, 그동안 제시된 여러 분류법과 상관성을 유지하면서 병리 및 내시경 소견 모두를 반영하기 위한 시드니 분류가 1990년 제정 및 1996년 개정되었다[4]. 그러나 이 분류법은 내시경 소견을 표현하고 진단에 적용하는 데에는 한계가 있고, 여전히 병리 진단에 초점이 맞추어져 있어서 내시경 소견의 기술에는 널리 사용되지 않고 있다. 하지만 지금까지도 몇 가지 단어들은 내시경 소견 기술에 사용되고 있는데, 점막의 부종, 발적, 유약성, 삼출물, 점막주름의 비후 또는 위축, 혈관의 투영성, 벽내출혈반, 결절 등이 그 예이다. 이 소견에 따라 발적/삼출성 위염, 편평 미란성 위염, 융기 미란성 위염, 위축성 위염, 출혈성 위염, 비후성 위염 및 장액 역류성 위염으로 분류한다. 이러한 분류는 아직 사용되고는 있지만 관찰되는 소견에 따른 분류로 임상적 의미(치료를 해야 하는가? 추적 관찰을 해야 하는가?)가 모호한 경우가 많아 한계가 분명히 존재할 수 밖에 없다. 또한, 추후 위암으로 진행할 수 있는 고위험 위염을 진단하고 이를 관리하기 위한 목적으로 사용되기에는 부족하다.

2. 위축성 위염과 장상피화생의 내시경 소견과 분류

시드니 분류에서는 위축성 위염에 대한 소견은 있으나 장상피화생에 대한 개념은 없다. 이는 내시경 소견보다 병리 소견을 중시한 결과이다. 우리나라에서는 자가면역성 위염이 많지 않아 시드니 분류에서 언급하는 자가면역성 위축성 위염과 전정부 위축성 위염 및 다발성 위축성 위염은 논외로 한다.

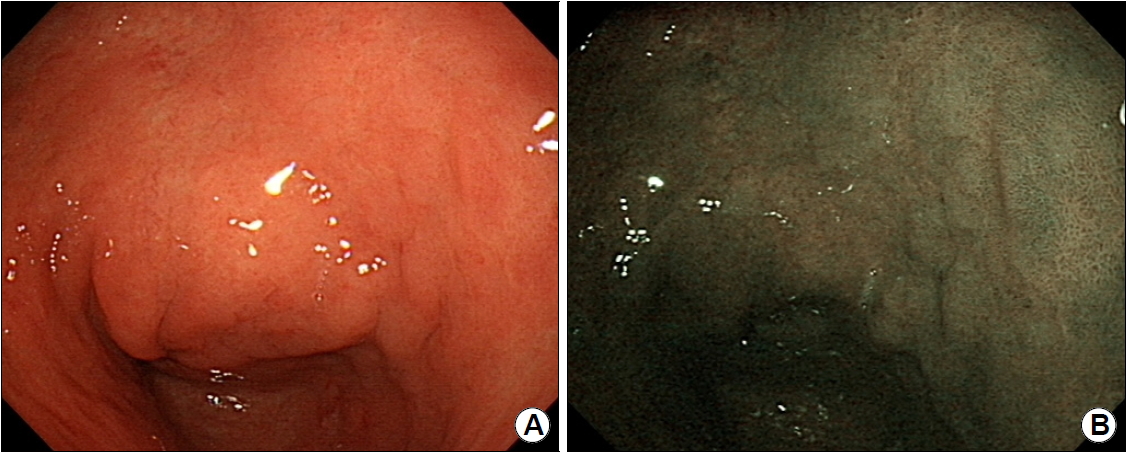

헬리코박터 감염에 의하여 생기는 위축성 위염은 표재성 위염에서 시작되어 위선 파괴로 인하여 위축으로 이어지는 것으로 이해되고 있다. 위축성 위염은 내시경 관찰 시 위주름이 없어지고, 얇은 점막층으로 인하여 점막하 혈관상이 잘 보이는 것으로 특정 지어진다(Fig. 1A) [5]. 혈관상이 잘 보이는 것으로 진단할 경우 진단의 민감도는 48%, 특이도는 87%이며, 위주름의 소실로 진단할 경우 민감도는 67%, 특이도는 85%로 보고되었다[6]. 위축이 진행할 경우 점막 상피가 과형성되어 장상피화생을 동반하게 되는데, 초기 단계에서는 내시경으로 진단하기 어렵지만 진행 시 백색반들이 조약돌 모양으로 군집하게 되고 내시경에서 두드러져 보이게 된다(Fig. 1B) [7].

Representative examples of (A) atrophic gastritis and (B) intestinal metaplasia. (A) The atrophic border is clearly discriminated by color, and the mucosal vascular pattern is evident. (B) Multiple whitish mucosal papules with background atrophy are a typical finding of intestinal metaplasia.

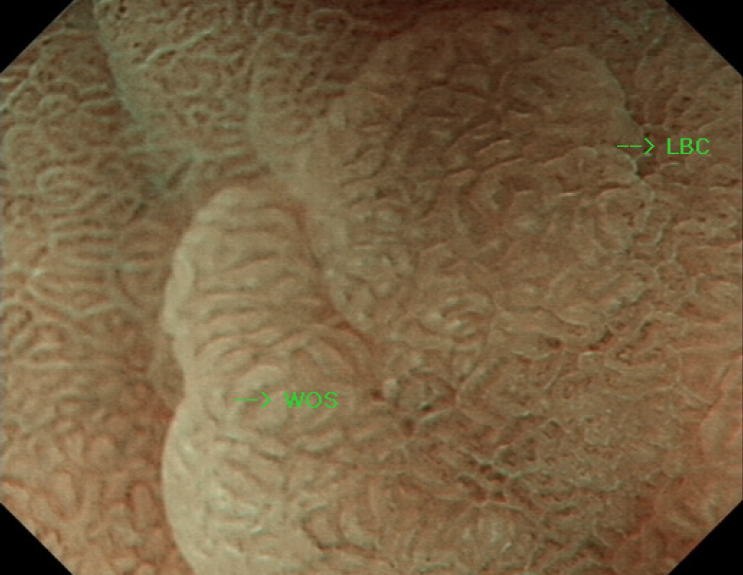

장상피화생은 백색광 내시경 단독으로 진단할 경우 협대역 내시경에 비하여 진단율이 떨어지며, 한 연구에서는 진단 정확도가 백색광 53%, 협대역 87%로 차이를 나타내었다(Fig. 2) [8]. 최근 고해상도 내시경의 사용과 확대 내시경의 보급으로 인하여 진단율의 상승을 보이고 있는데, 밝은 청색 융기(light-blue crest) 소견은 미세한 파란 또는 흰 선이 점막 상피의 능선(crest)을 따라 보이는 것으로 조직학적 장상피화생을 예측하는데 도움을 줄 수 있다 [9]. 또한, 점막하 미세혈관을 따라 흰 불투명 물질(white opaque substance)을 관찰하는 것도 도움이 된다(Fig. 3) [10]. 최근 여러 연구에서도 백색광 내시경과 협대역 내시경의 조합을 통하여 위축과 장상피화생의 진단율을 높일 수 있는 것으로 발표하고 있다 [11,12]. 공초점 레이저 현미경 내시경(confocal laser endomicroscopy)이 개발되었으나 아직 널리 쓰이고 있지는 않다. 이를 이용한 진단 연구도 진행되고 있는데, 최근의 메타분석에 의하면 민감도는 92%, 특이도는 97%에 달하여 조직검사 없이 진단하는데 도움을 줄 수 있을 것으로 생각한다[13,14].

Endoscopic findings of intestinal metaplasia. (A) Intestinal metaplasia is not prominent in the white-light image. (B) However, it can be clearly observed as a mucosal elevation in the narrow-band image.

The magnifying endoscopy image obtained with narrow-band imaging shows light-blue crests (LBC) on the surface of the epithelium and white opaque substances (WOS) in the intervening part between crypt openings.

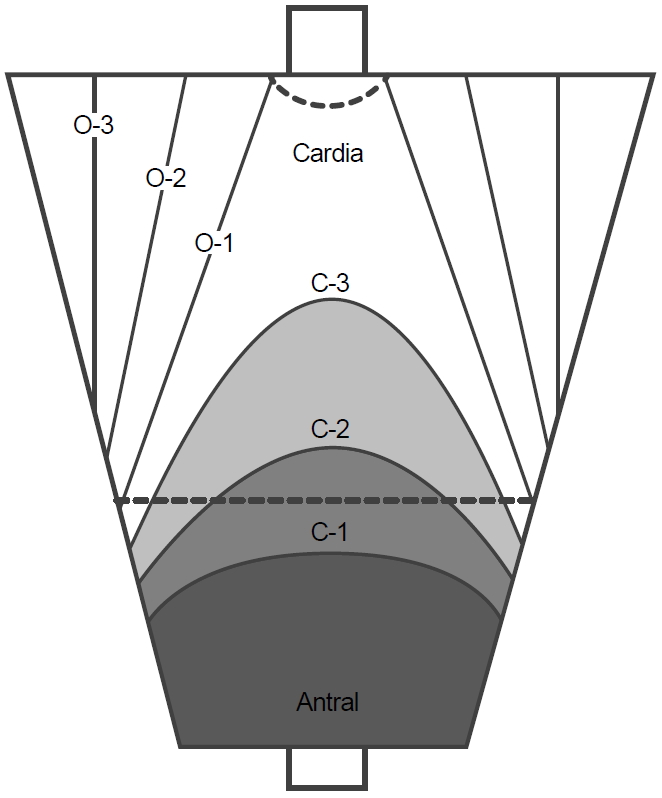

위축성 위염은 소만을 따라서 진행하여 분문부까지 확장하게 된다. Kimura-Takemoto 분류에서는 분문부까지의 위축을 폐쇄형이라 명명하고 그 범위에 따라 C1에서 C3까지 정의하고 있고, 분문부를 넘어서 위저부와 체부의 대만부를 따라 진행하게 되면 개방형이라 부르고 범위에 따라 O1에서 O3까지 정의한다[15]. 이 분류법은 오래되었지만 현재까지도 가장 많이 이용되고 있는 위축성 위염의 분류법이다(Fig. 4).

Kimura-Takemoto classification of atrophic gastritis. A closed-type gastric mucosa atrophy has an atrophic border between the fundic and pyloric mucosae in the antrum or lesser curvature of the gastric body. An open-type gastric mucosa atrophy has an atrophic boundary in the lateral wall or greater curvature of the gastric body.

장상피화생은 편평형, 융기형 및 함요형으로 분류할 수 있는데, 전정부에는 융기형이 많고 위각부는 편평형, 체부는 함요형이 많은 것으로 알려져 있으며, 대부분 서로 혼재되어 나타나는 경우가 많다. 그러나 이러한 분류는 쓰이고 있지는 않으며, 개방형 위축성 위염일수록 장상피화생 변화의 정도가 높아지는 것으로 알려져 있다[16].

3. 위축성 위염과 장상피화생의 새로운 분류법

지금까지의 분류법은 대부분 나타나는 표현형(phenotype)과 원인을 섞어서 만든 경우가 많고, 이것이 International Classification of Diseases-10에 반영이 되어 있어 이를 개정하기 위한 의도로 교토에서 위염의 분류에 대한 합의가 진행되었다[17]. 가장 큰 변화는 헬리코박터 유발성 위염이라는 분류가 새롭게 등장한 것이다. 그러나 이 분류에서도 여전히 원인에 따라 분류를 하고 있고, 내시경 소견과 병리 소견에 따라서 표재성 위염, 급성 출혈성 위염, 만성 위축성 위염, 화생성 위염, 육아종성 위염 및 비후성 위염으로 분류하고 있다. 따라서, 위암의 위험도에 따른 분류 및 진단에 대해서는 상세한 정보를 얻을 수가 없는 점이 문제이다.

교토 위염 분류의 원래 의도는 2013년 5월 일본소화기내시경학회에서 발표된 ‘위암 예방을 위한 내시경적 위염 분류안’이었다. 그러나 이는 교토 위염 분류에는 들어가 있지 않으며, 일본 내에서 작성 및 개정되어 현재까지 ‘위염의 교토 분류’로 개정 2판까지 출간된 상태이다[18]. 이 분류법에서는 위축성과 화생성 및 결절성과 비대성 위염의 네 가지 분류를 중요시하여 언급하였는데, 이는 각각 장형 위암과 미만형 위암의 위험성을 높이기 때문이다. 위염의 교토 분류에 대한 자세한 내용은 이미 언급된 바가 있어 논외로 한다[19,20]. 이 분류법은 기존의 위염 분류와는 다르게 헬리코박터 감염과 이에 따른 위암의 발생 위험에 중점을 두고 있으며, 여러 내시경 소견 중 위축, 장상피화생, 결절, 주름 비대 및 미만성 발적의 다섯 가지를 중심으로 하고, 병리 소견 대신에 내시경 소견을 중심으로 하였다는 데에 그 의의가 있다. 주관적인 내시경 소견을 객관화된 수치로 나타낸다는 점에서 하나의 시스템으로서의 가능성을 엿볼 수 있고, 헬리코박터 감염에 초점을 맞추었기 때문에 위암의 예방이라는 관점에서도 효용성이 있으나 분류가 나오기까지의 과정에서 근거가 부족하고 분류를 이용한 장기 연구가 없다는 점 및 점수 체계가 조금 복잡하다는 측면에서 단점이 존재한다. 향후 이를 간소화시키고, 임상에 적용한 장기 연구를 통하여 그 효용성을 증명하는 것이 필요하겠다.

4. 내시경 소견과 병리 진단 일치도 및 위암 위험도 예측

내시경에서 위축 및 장상피화생으로 진단하더라도 실제 조직검사에서 그렇게 나오지 않는 경우가 많고, 반대의 경우도 존재한다. 따라서, 내시경으로 검사를 하는 입장에서는 병리검사 없이 내시경으로 정확하게 이를 진단하는 것이 무엇보다 중요하다. 국내의 한 연구 결과를 보면 위축성 위염의 경우 민감도 및 특이도가 전정부에서 61.5%, 57.7%, 체부에서 46.8%, 76.4%로 보고되었으며, 장상피화생의 경우 민감도 및 특이도가 전정부에서 24.0%, 91.9%, 체부에서 24.2%, 88.0%로 보고되었다[7,21]. 이렇듯 내시경으로 위축과 장상피화생으로 진단하는 데에는 한계가 있는 것처럼 보인다. 그러나 이들 연구는 현재 시점에서 다시 생각해볼 필요가 있다. 왜냐하면 이전에 비하여 내시경 진단 기법이 더 발전되었으며, 최근 들어 고해상도 내시경이 출시되면서 이전과는 다르게 진단 정확도가 더 높아질 가능성이 있기 때문이다.

유럽을 중심으로 위 조직 생검을 통하여 병리 소견으로 위축 및 장상피화생의 정도를 평가하기 위한 방법으로 Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA)와 Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) 분류가 제창되었다. 초기 OLGA 분류의 평가는 병리의사 간의 불일치가 높은 문제가 있어 OLGIM 분류가 대두되었으며, OLGIM은 OLGA에 비하여 위암과의 관련성을 평가하는데 더 뛰어난 것으로 발표되었다[22]. 그러나 OLGIM 분류에 따라 그 위험성을 평가하기 위해서는 위 생검을 전정부 4개, 위각부 2개, 위체부 4개, 분문부 4개로 총 12개의 조직을 얻어야 하므로 임상에서 사용하기에는 어려움이 있다. 따라서 이러한 병리 소견을 내시경으로 대체하고자 하는 연구가 진행되는 것은 당연한 것으로 보인다. 최근 발표된 유럽의 연구에서는 내시경(고해상도 백색광 내시경 및 협대역 내시경)으로 장상피화생을 평가(Endoscopic Grading of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia, EGGIM)하여 조직학적 일치 정도를 비교하였다. 이 연구에서는 5군데(전정부 소만과 대만, 위각부 및 체부 소만과 대만)의 장상피화생 정도를 평가(없는 경우 0점, 30% 미만 1점, 30% 이상 2점)하여 점수를 합한 것으로 정도를 평가(0~10점)하였으며, 내시경으로 의심되는 경우 의심 부위를 조직검사하고, 의심되지 않는 경우에는 무작위 생검을 시행하였다. 병리 평가에서 OLGIM III/IV로 진단된 경우 4점 이상을 기준으로 하였을 때, area under the curve (AUC) 값이 0.96 (95% CI 0.93~0.98)으로 나타나 내시경 검사만으로 쉽게 위암의 위험도를 평가할 수 있다고 주장하였다[23].

내시경 소견과 병리 소견의 일치도가 높다면 내시경 소견만으로 위암의 위험도를 예측할 수 있을 것이고, 이는 임상에서 유용하게 사용될 수 있다. 일본의 한 연구에서는 의무기록을 후향적으로 검토하여 내시경 상 위축의 정도와 다른 위험인자를 분석하고, 위암 발생의 위험도를 구하였다. 다변량 분석에서 나이, 위축의 정도, 궤양 및 혈중 요산(uric acid)치가 위험인자였다. 단변량 분석에서 위축이 심한 경우에 추적검사에서 위암의 발생이 높게 나타났으며, 심한 위축이 있는 경우 위암의 연간 발생률은 0.31%로, 위축성 위염이 덜한 경우에 비하여 약 3배의 위암 위험도를 보였다[24]. 위축 소견 외에 내시경에서 관찰되는 장상피화생의 정도를 내시경으로 점수화(EGGIM)하고[8], 이를 OLGA 및 OLGIM과 함께 분석하여 위선종 및 조기 위암 환자를 대상으로 그 발생의 위험도를 대조군과 비교한 연구가 유럽에서 발표되었다. EGGIM 점수가 5점 이상인 경우가 대조군에 비하여 선종 및 조기 위암군에서 많았으며, OLGA 및 OLGIM 과 함께 다변량 분석에서 유효한 변수로 나타났다(EGGIM 5~10점, adjusted OR 21.2, 95% CI 5.0~90.2) [25]. 이 연구는 장상피화생의 병리학적 분류와 함께 내시경 분류도 위암의 위험을 예측하는 데 유용하다는 것을 보여준 첫 연구라는데 의의가 있다.

앞서 언급한 문헌들은 대규모 연구가 아니기 때문에 앞으로 많은 연구를 통하여 검증이 필요하겠다. 그러나 이러한 시도들이 지속적으로 이루어진다면 비교적 간단한 방법으로 위암의 위험도를 평가할 수 있는 분류법이 나올 것으로 기대한다.

결 론

내시경의 발전과 더불어 위염의 분류도 발전을 해왔다. 초기에 병리 소견과 원인을 중심으로 기술되던 방식들이 현재에 와서는 임상적 의미와 위암과의 연관성을 중심으로 기술되고 있다. 그 가운데 위축성 위염과 장상피화생은 헬리코박터 감염으로 인한 결과이고, 위암과의 연관성이 높기 때문에 많은 관심을 받으면서 아직도 진단과 분류에 대한 연구가 진행되고 있다. 새로운 내시경 진단 기법을 통하여 이를 정확히 진단하고 분류하려는 시도가 계속되고 있으나 아직 임상에 적용되고 널리 사용되기 위해서는 좀 더 간단한 방법이 나와야 하고 많은 근거가 있어야 한다. 이러한 연구들이 지속되어 조만간 임상에 적용됨으로써 진단 및 치료와 추적 관찰에 사용될 수 있을 것으로 기대한다.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.