위점막 조직 검사에서 불명확한 신생물로 보고 시의 접근

Approach for the Management of Indefinite-for-neoplasia Lesions Detected on Gastric Mucosal Biopsy

Article information

Trans Abstract

Indefinite-for-neoplasia is an expression used to describe lesions in which carcinoma or dysplasia cannot be clearly and conclusively established via biopsy. Gastric indefinite-for-neoplasia may represent a reactive change secondary to inflammation in some patients; however, some lesions are eventually diagnosed as dysplasia or carcinoma. Follow-up endoscopic biopsy is commonly performed in patients with gastric indefinite-for-neoplasia lesions. Nonetheless, patients may undergo resection based on a high index of clinical suspicion for dysplasia or carcinoma based on endoscopic findings. Accurate target biopsies of the lesion and effective communication with pathologists are required to improve diagnostic accuracy and avoid unnecessary re-examinations. It is important to establish endoscopic findings useful in differentiating lesions that require resection. In this review, we describe the approach for the management of indefinite-for-neoplasia lesions detected on gastric mucosal biopsy and the characteristics of lesions that require resection.

서 론

위의 불명확한 신생물(gastric indefinite for neoplasia)은 병리 진단에서 종양인지 아닌지 명확하게 결론 내리기 어려운 경우에 사용하는 용어이다. 조직 검사에서 명확하게 이형성증(dysplasia)이나 암(carcinoma)으로 진단되지 않았으나 비정형 세포(atypical cell)나 재생 비정형(regenerative atypism)이 관찰되는 경우로 개정된 Vienna 분류에서 범주 2에 해당하는 병변이다[1]. 위의 불명확한 신생물은 병리 결과지에 재생 이형성(regenerative atypia), 비정형 상피(atypical epithelia), 비정형 샘(atypical gland) 혹은 비정형세포(atypical cell)로 보고된다. 이런 표현들은 정상에서 벗어나지만 신생물(neoplasia)을 완전히 진단하지는 못하는 세포 구조의 왜곡(cellular architectural distortion) 혹은 핵의 이형성(nuclear atypia)을 나타내는 경우에 사용하는 병리학 용어들이다[2,3]. 정확한 진단에 필요한 조직 표본의 질과 양이 부족하고 암의 가능성이 있기 때문에 재조직 검사를 권고하게 된다[4,5]. 불명확한 신생물의 최종 조직 결과는 정상 조직 혹은 염증부터 이형성증, 위암까지 다양하게 확인될 수 있으며 여러 연구에서 이형성증은 5~17%, 위암은 21~37%까지 보고되었다[6-10]. 위의 불명확한 신생물은 전암 병변 혹은 이미 악성일 가능성이 있는 병변이나 아직 이에 대한 진료 지침이 없고 추적 내시경의 시기나 횟수 또는 바로 절제를 하는 기준이 없는 상태이다. 본 종설에서는 위점막 조직 검사에서 불명확한 신생물이 보고되었을 때 임상적으로 가능한 접근에 대해 참고문헌들을 통해 검토해보고 이에 대한 해결책을 제시해 보고자 한다.

본 론

1. 위의 불명확한 신생물의 정의, 진단 이유

1) 위의 불명확한 신생물의 정의와 의미

위내시경 조직 생검 결과에서 불명확한 신생물이라는 것은 위장관 상피 종양(gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia)에 대한 개정된 Vienna 분류에서 범주 2에 해당하는 병변으로 암종이나 이형성증으로 명확히 판정되지 않는 경우를 지칭한다[1]. 이 진단은 염증으로 인한 조직의 반응성 변화(reactive change)에서부터 이형성이나 암종까지 명확히 구분되지 않는 경우로 비정형적인 소견이 관찰되지만 그 부위가 국소적이거나 정확한 진단을 하기에 조직의 양이 많지 않거나 조직의 질이 떨어져 진단을 내릴 수 없는 경우에 사용한다[2,3]. 특히 한국과 같은 위암 유병률이 높은 지역에서 위의 불명확한 신생물이 보고되면 의사나 환자들이 경각심을 갖게 되고 대부분 내시경 재검을 통한 재조직 검사를 시행하게 된다.

2) 내시경 조직 생검의 한계

위 상피 종양에 대한 생검 겸자를 이용한 내시경 조직 검사는 간단하면서 비교적 정확한 결과를 얻을 수 있는 첫 번째 진단 도구이나 생검 조직과 전체 병변에 대한 내시경 절제술 후 최종 조직 간의 불일치가 다양하게 보고되고 있다[11-13]. 연구들은 겸자 생검에서 저등급 이형성증이었으나 최종 절제 조직이 위암으로 진단되는 경우는 6.1~8.7%로 보고하였고 이 중 미분화형 위암도 1.4%, 점막하 침범 암도 0.1%까지 있었다고 보고하였다[11-13].

내시경 겸자 조직 검사와 최종 절제 표본 간의 불일치의 이유는 첫 번째로 병변에 대한 정확한 표적 생검이 안 되었을 가능성이 있다. 두 번째로 정확한 표적 생검이 되었다 해도 병변이 너무 작아서 혹은 핵심 병변이 초점 형태로 일부만 있을 가능성이 있고 예로 고등급 이형성증이나 조기 위암이 저등급 이형성증 배경에 일부만 존재할 수 있다[14]. 세 번째로 위 반지세포암종처럼 상피하로 퍼지는 병변의 경우 표적 생검이 어려울 수 있다[15]. 네 번째로 생검 겸자의 크기나 생검 횟수에 따라 진단율이 다를 수 있다[16,17].

2. 위의 불명확한 신생물의 최종 결과

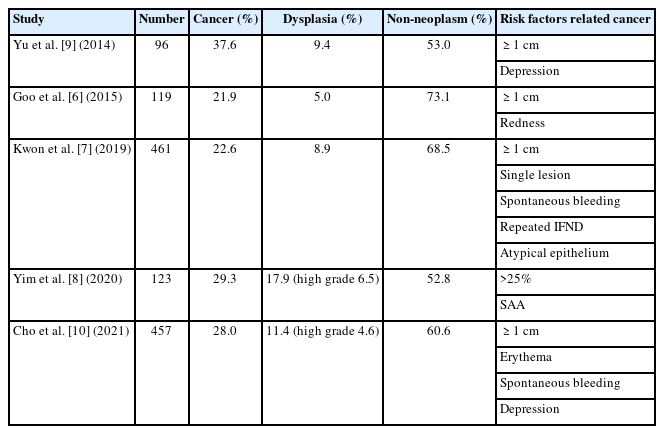

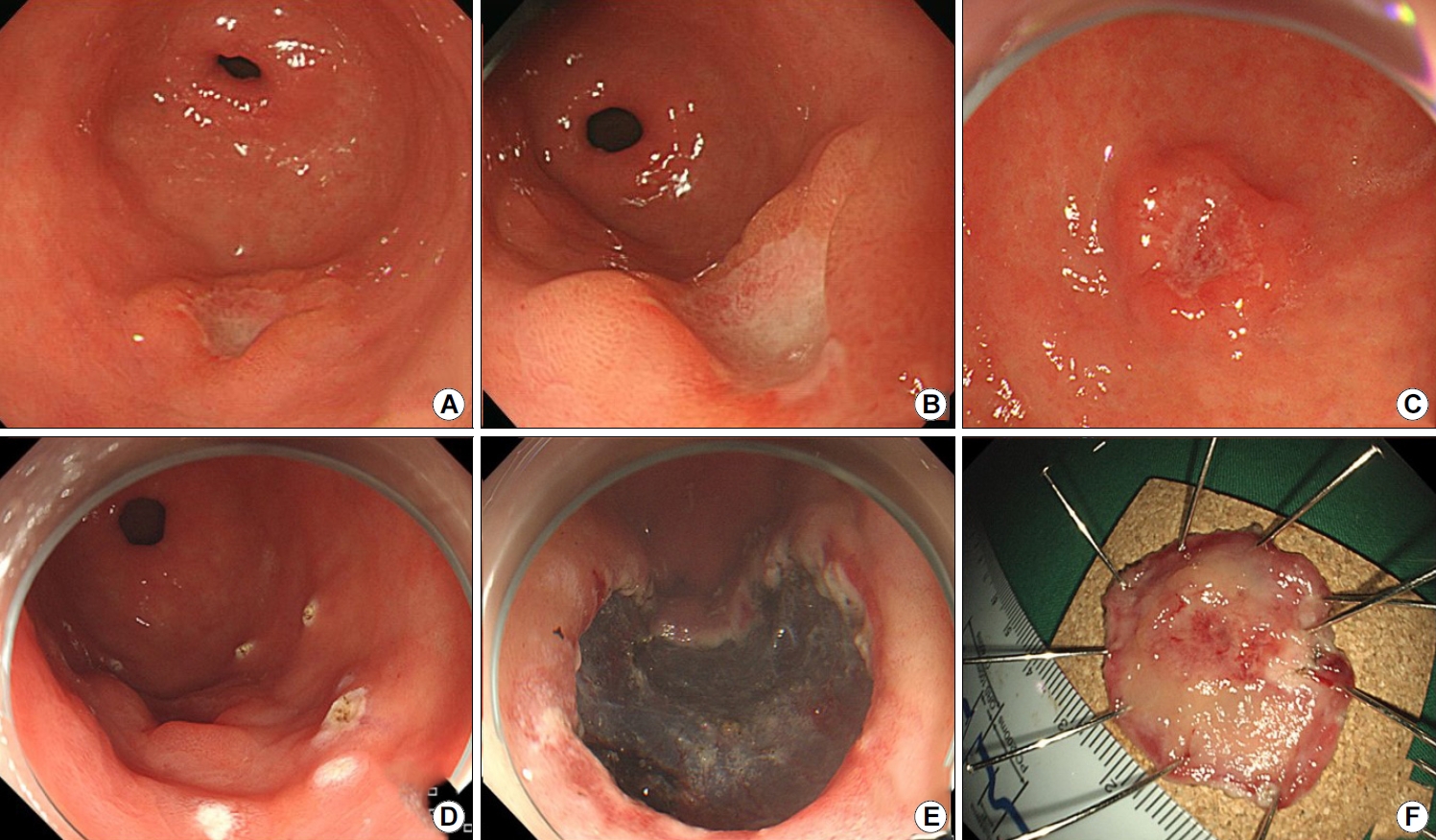

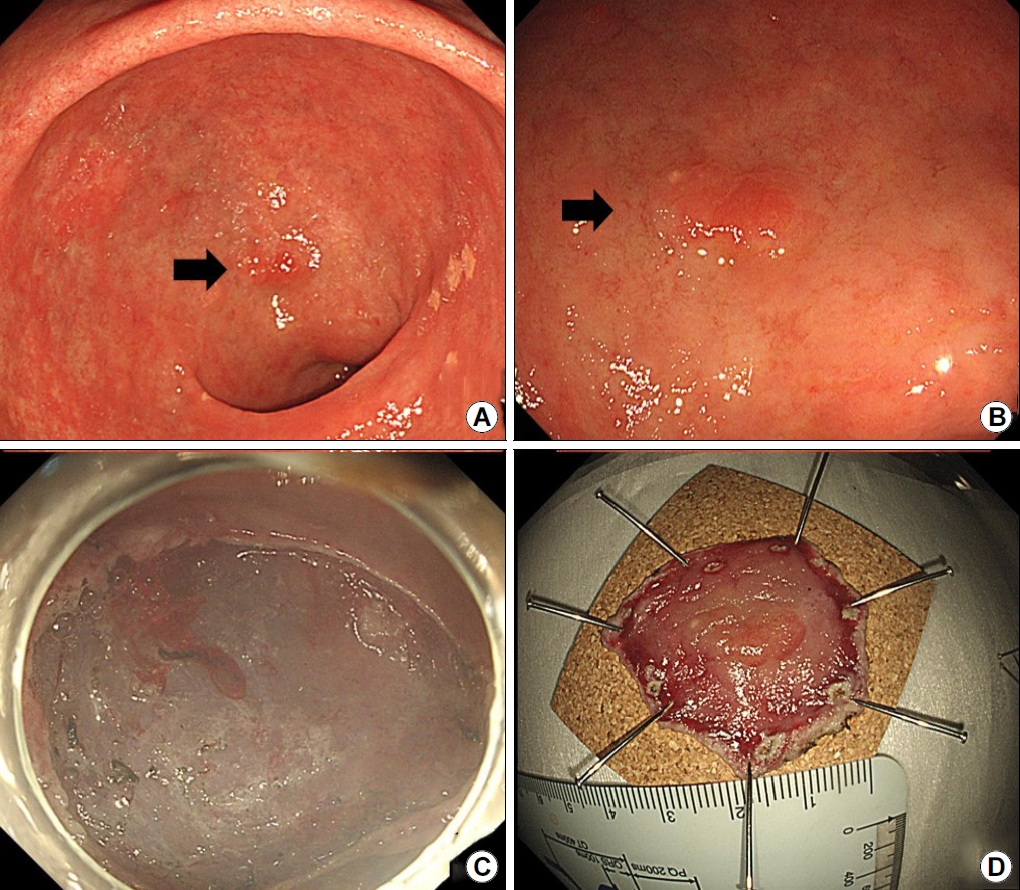

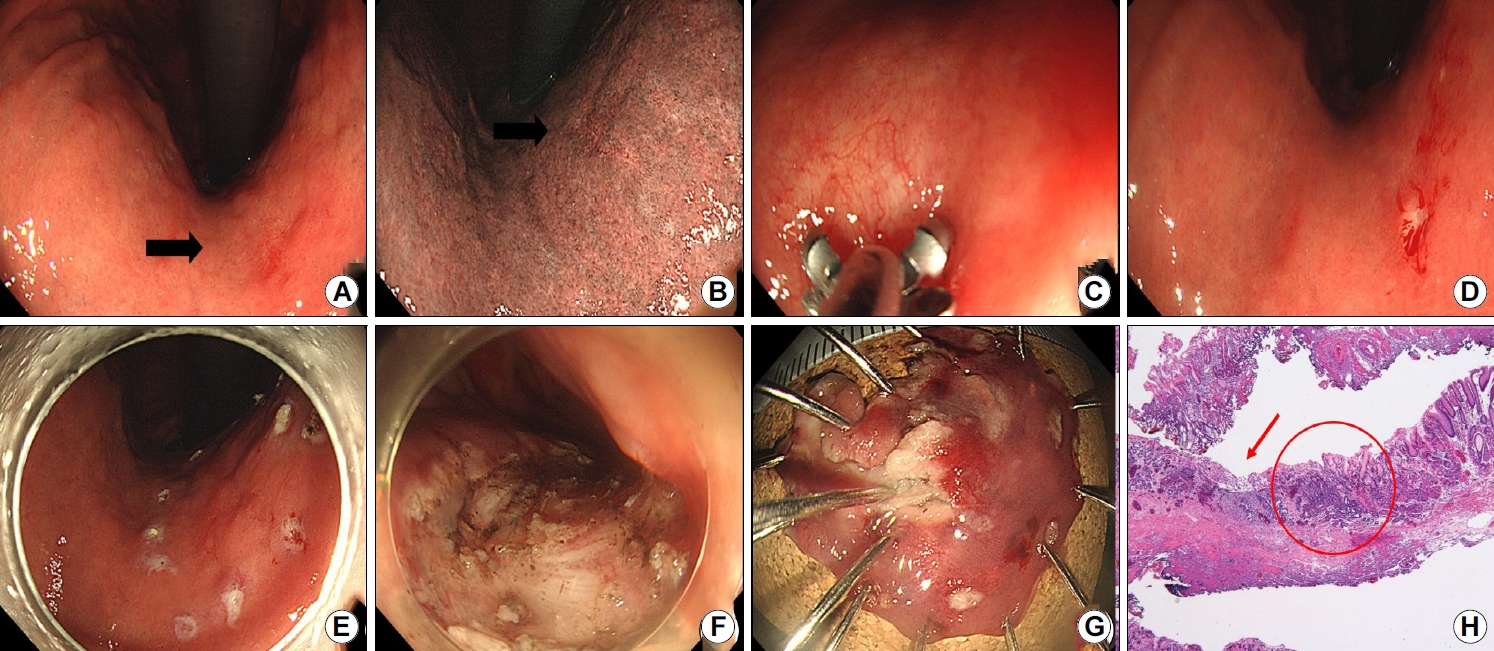

위 조직 검사에서 불명확한 신생물로 진단된 병변들은 최종적으로 특별한 이상 소견이 아니었거나(non-neoplasm) 이형성증, 조기 위암 그리고 드물게 진행성 위암까지 진단될 수 있다. 위궤양 역시 염증이 심할 때 조직 검사에서 비전형세포 형태가 관찰되어 악성으로 혼돈을 줄 수 있다. 위 조직 검사에서 불명확한 신생물로 진단된 병변들의 최종 결과를 비교한 연구들이 있었고 이들 중 내시경 절제술을 시행한 환자들만 대상으로 한 연구들은 이형성증이나 위암의 비율이 너무 높아 제외를 하면 총 5편의 연구들이 있었다. 이들 연구들은 모두 최종 진단 결과로 이형성증, 암 그리고 종양이 아닌 경우로 나누어 분석하였다(Table 1) [6-10]. 조직 검사에서 위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고되었으나 내시경 절제나 수술로 암 혹은 이형성증으로 최종 진단된 각각의 증례 사진들을 첨부하였다(Fig. 1-4).

Representative case of a 66-year-old woman with a suspected malignant ulcer, which was reported as showing atypia on endoscopic forceps biopsy. Endoscopic submucosal dissection was performed for the diagnosis and treatment of this lesion. The lesion was diagnosed as submucosal invasive cancer. Depth of invasion was 2000 μm; hence, additional surgery was done. (A-C) Images showing an ulcer (20 mm) with an irregular border and a dirty base, located at the greater curvature of the distal antrum. (D-F) Images showing endoscopic submucosal dissection and resected specimen after en-bloc resection.

Representative case of a 68-year-old man initially diagnosed with an indefinite-for-neoplasia lesion . After the resection, the lesion was diagnosed as adenoma with low-grade dysplasia. (A, B) Images showing a flat, elevated mucosal lesion (10 mm) located at the lesser curvature of the antrum (arrow). (C, D) Images showing endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced ulcer and resected specimen after en-bloc resection.

Representative case of a 61-year-old man initially diagnosed with indefinite-for-neoplasia, who was definitively diagnosed as having an early gastric cancer. (A, B) Images showing a flat mucosal lesion with unclear margins and scar-induced changes at the lesser curvature of the gastric body (arrow). (C, D) Images showing endoscopic biopsy procedure and an artificial ulcer after the biopsy. (E-G) Images showing endoscopic submucosal dissection and resected specimen after en-bloc resection. (H) Image showing carcinoma (circle) and defects (arrow) secondary to previous biopsies near the cancer (H&E staining ×40).

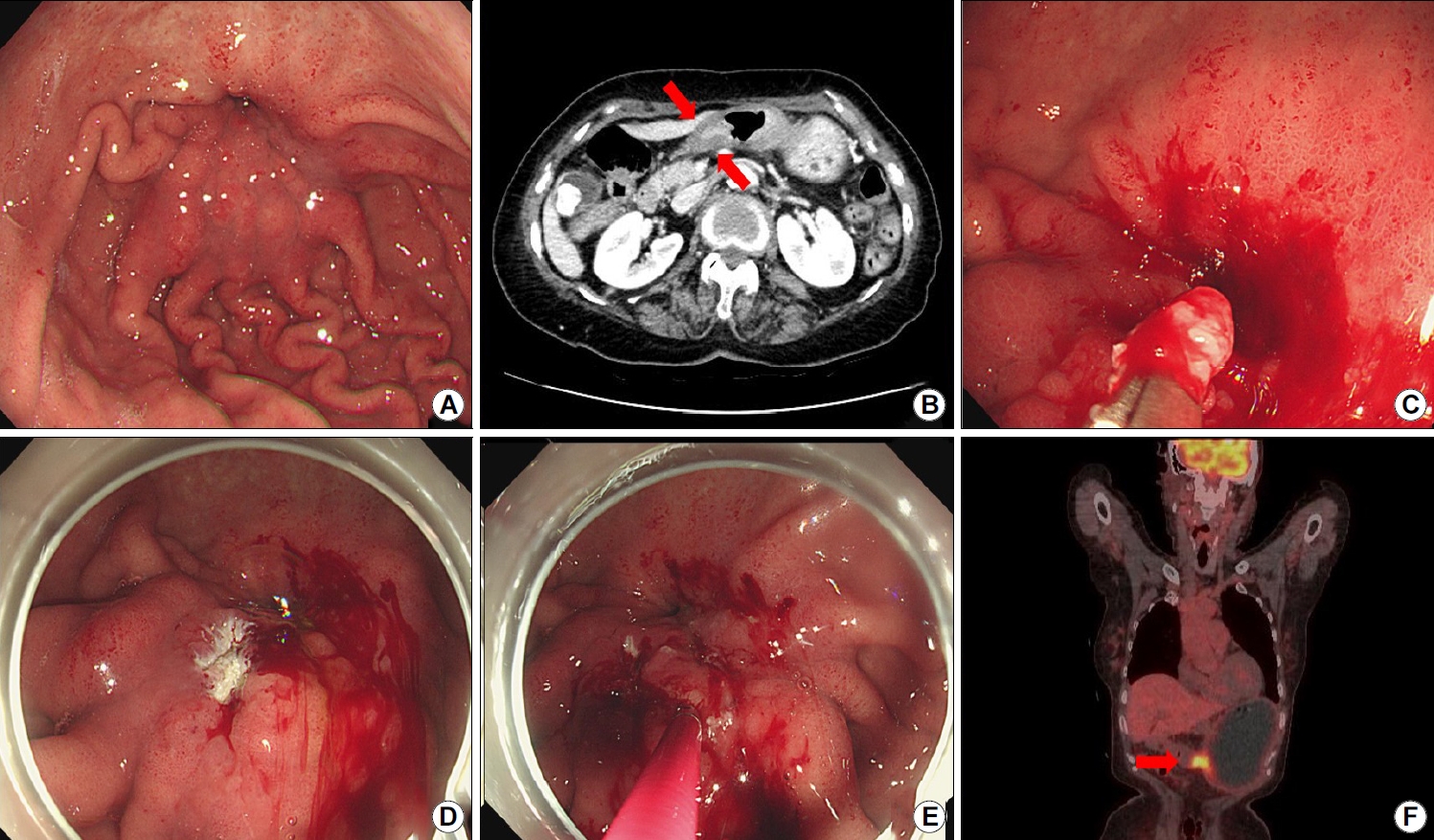

Representative case of a 72-year-old woman who initially underwent endoscopic forceps and unroofing biopsies. The lesion was diagnosed as atypia; however, final diagnosis after gastrectomy was gastric cancer. (A) Image showing convergence of gastric folds in the antrum associated with a high suspicion for gastric cancer. (B) Abdominal computed tomography scan showing diffuse wall thickening in the antrum (arrows). (C) Image showing endoscopic biopsy procedure. (D, E) Endoscopic images of an unroofing biopsy technique. (F) Positron emission tomography scan showing high uptake which is suspicious for malignancy (arrow). The patient underwent gastrectomy, and gastric cancer was confirmed.

1) 위염, 위궤양

위의 염증으로 인해 세포의 모양이 변할 수 있으며, 이런 병변들을 조직 검사하였을 때 병리학적으로 비전형세포(atypia)로 보고될 수 있고 위의 불명확한 신생물의 52~73% 정도까지 non-neoplasm으로 보고하고 있다[6-10]. 이런 병변들은 대부분 추적 내시경에서 자연 호전되거나 약제, 헬리코박터 감염 등의 원인인자를 제거하면 호전되는 경과를 보이나 내시경 절제까지 시행하여 조직학적으로 음성으로 판명되는 경우들이 드물게 있다.

위궤양의 조직 검사에서 비전형세포로 보고되는 경우 악성의 가능성이 있어 주의를 요하게 된다. 이런 경우 내시경 소견이 중요한데 전통적으로 궤양 주변 주름의 형태와 변연의 형태, 궤양 바닥의 형태로 양성 위궤양과 악성 위궤양을 감별할 수 있다. 한 연구에서 내시경 소견을 통한 악성 예측도를 융기된 변연은 94%, 불규칙한 변연은 91%, 지저분한 궤양 바닥은 79%로 보고하였다. 이 연구에서 첫 번째 내시경 소견과 조직검사 결과가 모두 양성 위궤양으로 보고되었을 때 최종적으로 암으로 진단된 경우는 없었으나 첫 번째 내시경에서 양성 위궤양의 소견을 보였던 환자들 중 2.5%는 최종적으로 암으로 진단되었다[18]. 다른 국내 연구에서는 불규칙한 변연과 융기된 변연이 악성 위궤양의 의미 있는 내시경 소견이었고 악성 위궤양의 37.5%이 최초 조직 검사에서 모호한 병리 진단으로 추적 내시경이 필요했다고 보고하였다[19].

2) 이형성증(dysplasia)

최초 조직 검사에서 불명확한 신생물로 진단된 병변들의 최종 결과를 확인한 연구들에서 이형성증으로 진단되는 비율은 5.0~17.9%로 보고하였다(Table 1) [6-10]. 이 중 두 연구에서 고등급 이형성증까지 분류하였고, 불명확한 신생물이 고등급 이형성증으로 나오는 경우는 각각 6.5%, 4.6%로 보고하였다[8,10]. 위선종 혹은 이형성증의 병리학적 정의는 위의 선 구조(glandular structure)를 유지하면서 관상(tubular) 혹은 유두상(papillary) 구조를 가지고 있는 선종성 상피세포(adenomatous epithelium)의 증식으로 정의할 수 있다[20]. 하지만 위의 이형성증 혹은 조기 위암에 대한 서구와 일본의 병리학적 분류 체계가 달라 혼선이 있으며, 고등급 이형성증의 경우 일본의 분류를 따르면 위암으로 진단될 수 있어 해석에 주의를 요한다.

3) 조기 위암

불명확한 신생물로 진단된 병변들은 최종적으로 21.8~37.6%까지 위암으로 진단되었다[6-10]. 대부분 T1a의 병기였으나 수술 혹은 내시경 절제 후 T1b 이상의 병기를 7.3% (9/123)로 보고한 연구가 있었다[8]. 한 연구에서는 미분화형 위암을 2.2% (10/461)로 보고하였다[7]. 암으로 진단 되는 위험인자를 분석하였을 때 1 cm 이상의 크기는 모든 연구들에서 암으로 진단되는 위험인자였고 그 외 점막 발적, 함몰, 자발 출혈이 두 가지 연구에서 공통되는 위험인자였다[6,7,9,10]. 병리학적으로는 병리 소견만 분석한 연구에서 구조적 비정형(structural atypia)이 핵의 비정형(nuclear atypia)보다 악성을 진단하는 데 더 도움이 되어 구조적 비정형의 범위(structural atypia area, SAA)가 25% 이상이 악성 진단에 가장 효과적인 병리 소견이라고 주장하였다[8]. 비슷하게 다른 연구에도 재생 비정형(regenerative atypia)보다는 비정형 상피(atypical epithelium)가 더 악성 위험도가 높다고 주장하였고 반복해서 불명확한 신생물로 진단되는 경우에 악성 위험도가 더 높다고 보고하였다[7]. 내시경이나 병리 소견에서 악성이 강력히 의심되면 적극적인 절제를 고려해야 하지만 추적 관찰 기간별로 분석한 연구에서 악성을 의심할 만한 소견이 없는 경우에 진단이 늦어져도 1년 이내면 예후에 차이가 없다고 주장하였다[7].

4) 진행성 위암

진행성 위암도 조직 검사에서 불명확한 신생물로 보고되는 경우들이 있고 진행성 위암의 경우 궤양을 동반한 경우가 많아 양성 궤양과 감별이 어려울 수 있고 조직 검사에서 암세포가 확인되지 않는 경우가 드물지 않게 있다. 진행성 위암은 조기 위암과 다르게 빠르게 진행하고 전이가 발생할 수 있어 주의를 요하고 재검도 최대한 빨리 시행해야 한다. 불명확한 신생물의 최종 결과를 보고한 연구들에서 위암은 대부분 조기 위암이었으나 진행성 위암으로 진단된 환자가 3.1% (3/96) 있었던 연구가 있었다[9]. 한 연구에서 주름의 변화가 미분화형 위암이나 점막하층 이상 침범의 위험인자로 제시하였다[7].

3. 위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고되었을 때 접근 방법

위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고되었을 때 접근에 대한 권고안이 없고 관련 메타분석이나 종설도 없는 상태이다. 일반적으로 재조직 검사를 시행하게 되고 최근에는 내시경 관찰 소견이 발전하여 암이 강력히 의심되는 경우에는 정확한 진단 없이도 적극적인 절제를 고려하기도 한다. 그동안의 연구들을 참고하여 접근 방법을 정리해 보았다.

1) 내시경 재검 및 재조직 검사

위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고되었을 때 가장 먼저 생각하고 간단하게 해볼 수 있는 것은 재조직 검사이겠다. 생검 겸자를 이용한 내시경 조직 검사는 간단하면서 비교적 정확한 결과를 얻을 수 있는 첫 번째 진단 도구이나 앞서 설명처럼 한계가 있다. 앞선 조직 검사에 비해 정확도를 높이기 위한 방법으로 크기가 큰 겸자를 사용하거나 같은 병변에 대해 조직 검사 횟수를 여러 번 할 수 있겠다. 하지만 큰 겸자를 사용하는 것은 정확도를 높일 수 없는 것으로 알려져 있다[17]. 반면에 여러 번 조직 검사하는 것은 진단율을 높일 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다. 위암의 진단에 있어 한 번의 조직 검사의 진단율이 70%였던 반면에 3회 더 추가로 조직 검사 시에는 진단율이 95% 이상으로 알려져 있다[16]. 하지만 여러 번 조직 검사 시에 출혈이나 조직의 변형 혹은 섬유화가 문제가 될 수 있다. 임상에서 출혈이 문제가 되는 경우는 극히 드물지만 병변에 대해 내시경 절제를 고려한다면 여러 번 조직 검사로 인한 섬유화는 문제가 될 수 있다. 따라서 정확한 첫 번째 조직 검사가 가장 중요하겠다. 정확한 조준 생검이 된다면 진단율을 92.3%까지 보고하고 있다[21]. 추후 내시경 절제까지 고려하여 첫 번째 조직 검사를 색조 변화나 함몰이 있는 부위에 최대한 정확하게 하고 1~2회 정도 추가로 조직 검사를 하는 것이 현실적으로 판단된다.

추적 내시경 검사의 시기 역시 정해진 바가 없으나 내시경 소견이나 조직 검사 결과에서 악성이 의심된다면 최대한 빨리 추적 내시경을 시행해야 하고, 그렇지 않은 경우 실제 임상에서는 3개월 혹은 6개월 뒤 시행하고 있다. 추적 관찰 기간이 명시되어 있는 연구들에서도 3개월 혹은 6개월 뒤 내시경을 시행하였다[6,7,22]. 한 연구에서는 암의 위험인자가 있는 병변은 3개월 뒤, 없는 병변은 6개월 뒤로 추적 검사할 것을 권고하였고 악성을 의심할 만한 소견이 없는 경우에 진단이 늦어져도 1년 이내면 예후에 차이가 없다고 주장하였다[7]. 요약하면 내시경 재검은 악성이 의심된다면 최대한 빨리 시행하고 그렇지 않다면 3개월 혹은 6개월 뒤에 시행하며 재조직 검사 시에는 첫 번째 생검을 최대한 정확하게 조준 생검해야겠다.

2) 병리과와의 상의

위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고되었을 때 결과를 기계적으로 받아들이기보다 병리과와의 소통이 중요하겠다. 위의 불명확한 신생물은 병리적으로 재생 비정형(regenerative atypia)과 비정형 상피(atypical epithelium)로 구분할 수 있다. 재생 비정형은 과염색성 핵(hyperchromatic nucleus), 다양한 핵의 크기와 모양, 핵의 위치 변화, 핵-세포질 비율의 증가 등 주로 핵의 이상을 표현하는 용어이며 비정형 상피는 국소화된 세포 군집 혹은 불규칙한 형태의 샘 등 구조적인 왜곡이 관찰될 때 사용하는 용어이다[23]. 핵의 이상인 재생 비정형보다 구조의 이상인 비정형 상피가 악성 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 알려져 있다[7,8]. 조직 결과에서 재생 비정형의 경우 추적 내시경 조직 검사를 6개월 뒤에, 비정형 상피의 경우 3개월 뒤에 할 것을 권고한 연구도 있었다[7]. 위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고받았을 때 병리과와 소통해서 조직 슬라이드를 다시 분석하여 더 악성 가능성이 높은 소견이 없는지 확인해보고 상의하는 것이 환자의 추적 내시경 시기 결정이나 치료 방향 결정에 도움이 될 수 있겠다.

3) 내시경 절제술

위의 불명확한 신생물은 진단이 명확하지 않으므로 정확한 진단을 위한 내시경 재검, 재조직 검사가 원칙이겠으나 상황에 따라 절제를 바로 시행하는 경우들이 종종 있다. 특히 한국처럼 내시경 절제를 많이 시행하고 있는 지역에서는 악성이 강력히 의심될 때 절제를 해 볼 수 있겠다. 하지만 정확한 진단 없이 바로 절제는 반드시 악성이 의심되는 상황에서 시행해야겠다. 위의 불명확한 신생물에서 악성이 의심되는 경우는 앞서 언급한 것처럼 1 cm 이상의 크기와 발적, 자발 출혈, 함몰 같은 특징들이 있겠다[6,7,9,10]. 실제 연구들에서 5.7~34.6%의 환자들이 암이나 이형성증의 확실한 진단 없이 내시경 절제를 시행하였고 이 중 71.4~87%가 암이나 이형성증으로 진단되었다[6,7,9,10]. 내시경 절제술 전에는 조기 위암을 시사하는 내시경 소견을 반드시 숙지하고 있어야겠다.

4) 수술

위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고된 병변들 중에 진행성 위암이나 점막하층 침범 암으로 수술적 치료가 필요한 병변들이 있을 수 있다. 수술은 위를 절제하는 침습적인 치료 방법으로 신중하게 결정해야하며 최대한 조직학적으로 암이 진단된 후에 진행하는 것이 바람직하다. 하지만 진행성 위암의 경우 빠른 진행과 전이를 일으킬 수 있고 반복되는 조직 검사가 시간을 지연시킬 수 있어 바로 수술을 시행하는 경우가 매우 드물게 있다. 위의 불명확한 신생물의 최종 결과를 보고한 연구들에서도 수술을 시행한 환자들이 3.7~20.8%까지 있었고 정확한 암 진단 없이 바로 수술을 진행했던 환자들도 각 연구별로 4~11명 정도 있었다[6-10]. 연구들 중에 수술을 시행하였으나 암세포나 이형성증이 확인되지 않은 환자도 있었다[10]. 정확한 조직 검사와 진단이 중요하겠으나 진행성 위암이 강력히 의심된다면 재검과 재조직 검사로 인해 시간을 지체하면 안되겠다.

5) 기타

위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고되었을 때 병변을 확대 내시경(magnifying endoscopy)으로 관찰해 볼 수 있겠다. 조기 위암의 진단에 확대 내시경의 유용성은 이미 잘 알려져 있다[24,25]. 이를 위의 불명확한 신생물의 진단에도 적용하여 demarcation line을 확인하고 미세혈관의 구조(microvascular architecture)와 미세표면 형태(microsurface structure)를 관찰하여 악성의 가능성을 판단하는 데 도움을 얻을 수 있겠다. 위의 불명확한 신생물에 확대 내시경을 적용한 연구는 없었으나 확대 내시경으로 조기 위암에서 비정형의 정도와 범위를 확인한 증례보고가 있었고[26] 최근에 확대 내시경을 이용하여 조기 위암과 선종을 감별하는 연구가 있었다[27]. 병변의 감별뿐만 아니라 확대 내시경은 이상 있는 부위를 정확히 조준 생검을 하는 데도 사용할 수 있겠다.

다음으로 위의 불명확한 신생물로 보고되었을 때 헬리코박터 제균 치료를 고려해 볼 수 있겠다. 위의 불명확한 신생물이 확인되었을 때 헬리코박터 제균 치료를 해야한다는 권고 사항은 없다. 하지만 이론적으로 비정형은 염증과 관련 있을 수 있고 헬리코박터 감염은 급, 만성 염증의 원인이 될 수 있으며 위암의 원인이 될 수 있다. 헬리코박터와 위의 불명확한 신생물의 관련성을 보고한 연구들이 있고[9,28] 이 중 한 연구에서는 헬리코박터 제균 치료 후에 재생 비정형이 호전됨을 확인할 수 있었다[28]. 헬리코박터 제균 치료 후에 위선종의 퇴화를 보고한 연구도 있었다[29]. 위의 불명확한 신생물의 내시경 추적 검사 사이에 헬리코박터 균 감염이 있다면 제균 치료를 하는 것도 하나의 전략이 될 수 있겠다.

결 론

위의 불명확한 신생물은 병리 진단에서 종양인지 아닌지 명확하게 결론 내리기 어려운 경우에 사용하는 용어로 실제 병변은 염증부터 진행성 위암까지 다양할 수 있고 실제 제거가 필요한 이형성증이나 위암으로 최종 진단되는 경우가 많다. 아직 특별한 가이드라인이나 권고안이 없어 내시경 재검과 재조직 검사를 하고 있으나 내시경 소견이나 병리적으로 악성이 강력히 의심되는 경우 정확한 진단 없이 바로 내시경 절제, 극히 일부에서 수술까지 바로 시행하기도 한다. 내시경 재검 시에는 가장 이형성이 심할 부위를 정확하게 조준하여 시행하는 첫 조직 검사가 가장 중요하겠다. 재검에서도 명확하게 진단이 내려지지 않으나 암이 강력히 의심되는 경우 바로 절제를 고려할 수 있겠으나 이런 경우 암을 의심하게 하는 내시경 소견들을 숙지하고 있어야 되고 다양한 병변들을 관찰하는 경험이 필요하겠다. 병리과 의사와 상의가 중요하며 병리학적으로 암의 위험이 높은 경우 빠른 재검 혹은 절제가 필요할 수 있다. 재검의 시기가 명확히 정해져 있지 않으나 주름의 변화 등 진행성 위암이 의심되는 경우 재검에 시간을 지체하면 안 되겠다.

Notes

There is no potential conflict of interest related to this work.