Helicobacter pylori 음성 위암

Helicobacter pylori-negative Gastric Cancer

Article information

Trans Abstract

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-negative gastric cancer is diagnosed when gastric malignancies are found in patients in H. pylori-naïve stomachs. There are four types of noncardiac H. pylori-negative gastric cancers. The signet ring cell-type poorly cohesive carcinoma is most common, followed by the chief cell-predominant type gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland. Extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the corpus and well-differentiated pyloric gland cancers are rare outside Japan because of country-specific differences in diagnostic criteria. In endemic areas of H. pylori infection, strict criteria are required for diagnosing an H. pylori-naïve stomach. Both invasive and noninvasive H. pylori tests should show negative results in a subject without a history of H. pylori infection. Furthermore, the serum pepsinogen (PG) assay and endoscopic findings of the background gastric mucosa are required to discriminate subjects with past infections owing to spontaneous regression or unintended eradication of H. pylori. There should be no gastric corpus atrophy (PG I ≤70 ng/mL and PG I/II ≤3.0). Gastroscopy should reveal a regular arrangement of collecting venules without gastric xanthoma, metaplastic gastritis, or advanced atrophy over the angle. On biopsy, there should be no gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, neutrophils, or H. pylori infiltration, and only a mild degree of mononuclear cell infiltration is permitted. The types and characteristics of noncardiac H. pylori-negative gastric cancers are summarized in this review, along with current diagnostic challenges found in Korea.

서 론

헬리코박터 파일로리(Helicobacter pylori, H. pylori) 균에 감염된 적이 없는 미감염자에서 발생한 위암을 H. pylori 음성 위암이라고 한다. H. pylori 미감염 위(H. pylori-naïve stomach)는 감염력이 없는 사람이 침습적인 검사와 비침습적인 검사 모두에서 H. pylori 음성 소견을 보이면 의심할 수 있지만 H. pylori 감염이 흔한 지역에서는 보다 까다로운 기준이 필요하다[1]. 균이 저절로 소멸되거나 의도치 않게 우연히 제균된 과거 감염자를 제외하기 위해서 배경 위점막의 내시경 소견과 조직검사 소견을 확인하고 혈청 펩시노겐(pepsinogen, PG) 검사로 위체부의 위축(gastric corpus atrophy) 또는 혈청학적 위축(serologic atrophy)에 해당하는 PG I ≤70 ng/mL 및 PG I/II ≤3.0이 없는지 확인해야 한다[2]. 배경 위점막에서 균일한 혈관상이 관찰되고 과거 감염을 시사하는 황색종, 화생성 위염, 체부까지 진행된 위축성 위염이 없으면 미감염자로 진단할 수 있다[3].

한국인에서 H. pylori 미감염의 진단기준을 1) 제균 치료의 과거력이 없고, 2) 혈청 항 H. pylori IgG 음성, 3) 조직검사에서 H. pylori 음성, 4) 신속요소분해효소검사(rapid urease test) 음성, 5) 위점막조직 배양 검사에서 H. pylori 음성, 6) 혈청 PG 검사에서 혈청학적 위축 없음, 7) 조직검사에서 장상피화생이나 위축 없음을 모두 만족하는 경우로 정의하였을 때, 위암 환자 627명 중 H. pylori 음성 위암의 유병률은 5.4%였다[4]. 한편, 일본에서는 배경 위점막의 내시경 소견으로 감염 상태를 판단하는 과정이 추 가되기 때문에 H. pylori 음성 위암의 유병률이 0.67%로 낮다[5]. 본문에서는 최근에 보고된 비분문부성(noncardiac) H. pylori 음성 위암의 종류와 특징에 대해서 살펴본 뒤, 진단 시의 문제점과 해결책에 대해서 고민해보고자 한다.

본 론

1. H. pylori 음성 위암의 종류

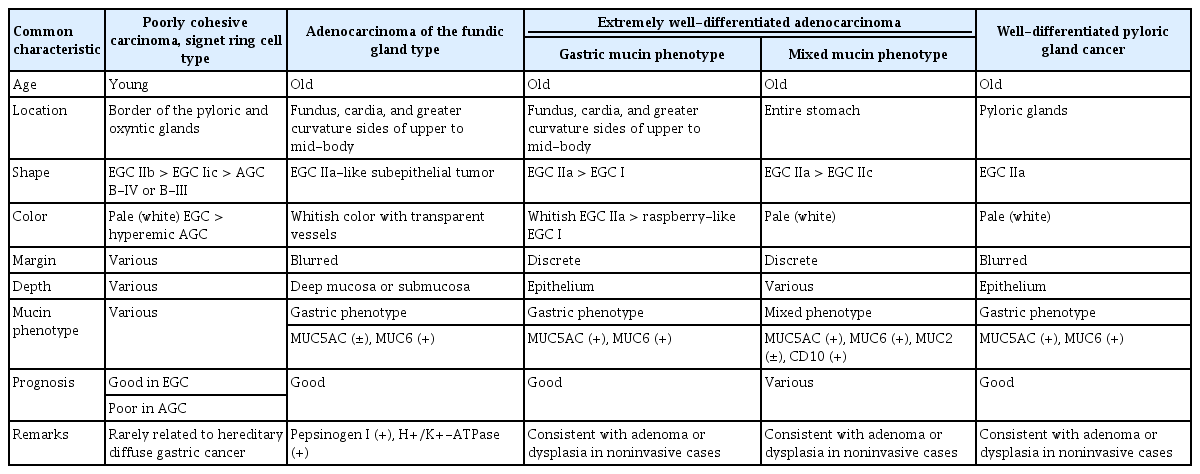

비분문부성 H. pylori 음성 위암은 발생 위치와 세포형에 따라 원위부에서 흔한 1) 인환세포암(signet ring cell carcinoma), 근위부에서 흔한 2) 위저선형 선암(fundic gland-type adenocarcinoma), 3) 초고분화도 선암(very or extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma), 4) 유문선에서 발생하는 고분화도 유문선암(well-differentiated pyloric gland cancer)으로 분류된다(Table 1). H. pylori 음성인 분문부암은 바렛 식도암과 함께 Siewert II형의 위식도 접합부암에 속하므로 제외하였다[6].

1) 인환세포암

저응집형암(poorly cohesive carcinoma)에 속하는 인환세포형의 위암으로, 비분문부성 H. pylori 음성 위암 중 가장 흔하다[7]. 주로 젊은 성인에서 진단되나 드물게 고령에서도 진단된다[8].

(1) 원인

서양에서는 인환세포암의 발생기전을 E-cadherin (Cadherin-1, CDH1) 변이로 인한 유전적 미만형 위암(hereditary diffuse-type gastric cancer)으로 설명한다[9]. 실제로 CDH1 변이가 진단된 미국인 20명에게 위내시경 검사를 한 결과, 12명에서 인환세포암이 발견되었고 5명은 미만형 위암의 가족력이 있었다고 한다[10]. 그러나 한국이나 일본에서는 동아시아형 cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA)를 지닌 H. pylori 감염에 의해 CDH1 변이가 유발되므로[11], 장형 위암에서도 CDH1 변이가 흔히 관찰된다[12]. 심지어 위암이 없는 H. pylori 감염자에서조차 CDH1 변이가 흔하며 제균 치료 시 변이가 사라진다[13]. 따라서 한국과 일본에서 진단되는 CDH1 변이를 서양인의 유전적 인환세포암과 혼동하면 안 된다. 매우 드물게 동양인 가족에서도 CDH1 변이로 인한 유전적 미만형 위암 증례가 보고되는데, 이 때는 서양에서처럼 예후가 불량하므로 전위절제술을 시행해야 한다[14].

한국이나 일본에서 진단되는 H. pylori 음성 인환세포암의 원인이 서양과 다를 것으로 추정되는 이유는 서양처럼 예후가 불량하지 않기 때문이다[15]. 특히 H. pylori 음성 인환세포암이 2 cm 미만으로 작을 때는 H. pylori 감염성 인환세포암에 비해 덜 침습적이며 천천히 자란다[16]. 동아시아 지역에서 발생하는 인환세포암의 가장 흔한 원인이 H. pylori 감염이라는 점을 고려할 때[17], 한국과 일본의 H. pylori 음성 인환세포암은 균이 사라진 후에 발생한 위암일 가능성이 있다. 본인도 모르는 사이에 앓고 지나간 경우, 위내시경과 혈청 검사 소견이 정상으로 회복되면 과거 감염을 증명할 수 없기 때문이다. 우리나라에서 진단된 H. pylori 음성 위암의 대부분은 젊은 나이에 발생한 인환세포암이었는데[18], 위축과 장상피화생 변화가 적은 어린 연령일수록 위점막이 회복되기 쉬우므로[19], 과거 감염자일 가능성을 배제할 수 없다.

(2) 내시경 소견

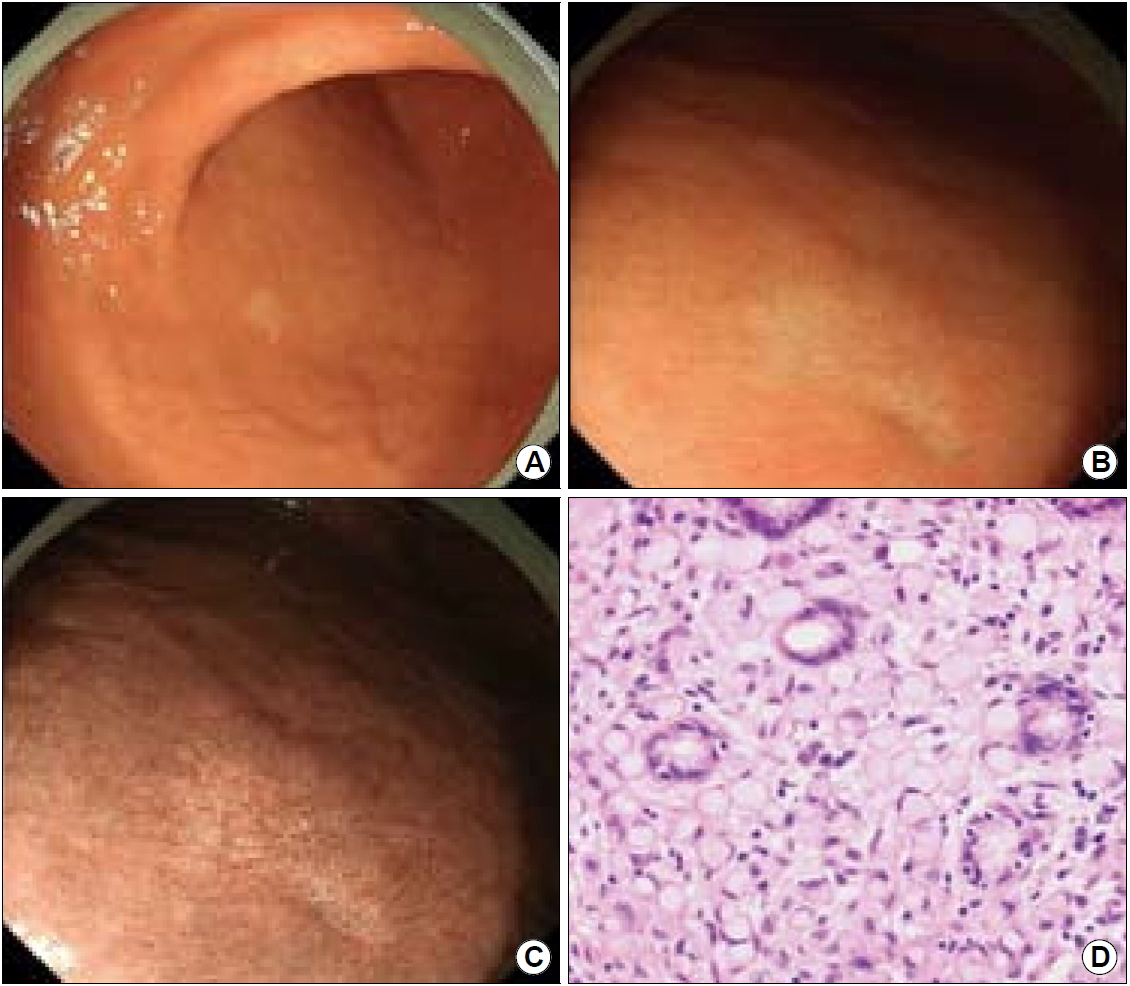

주로 원위부에서 발생하며 구체적인 위치는 유문선과 위저선의 경계선이다[20]. 조기 위암일 때는 편평한 조기 위암(early gastric cancer, EGC) IIb형(Fig. 1)이나 함몰된 EGC IIc형으로 보이다가 진행성 위암이 되면 궤양성 침윤을 보이는 보만(Borrmann) III형(B-III)이나 점막하 침윤이 심한 B-IV형으로 관찰된다[21]. 또한, 조기 위암일 때는 퇴색된 흰색으로 보이지만 암이 커지면서 붉은 진행성 위암으로 변해간다. EGC IIb인 경우, 색소를 뿌리면 병변이 가려지므로 색소내시경보다 특수광 내시경으로 관찰한다.

T1aN0M0-staged signet ring cell type, poorly cohesive carcinoma. (A) On conventional endoscopy, an 8 mm pale lesion is noticed in the greater curvature side of the lower body. (B) The lesion is slightly more depressed than the surrounding mucosa indicating early gastric cancer IIc. (C) On narrow band imaging endoscopy, discolored areas are found at the cancer margins. (D) On H&E staining, signet ring cells are noticed in the mucosa without venous or lymphatic invasion. Adapted from the article of Ueyama et al. Jpn J Helicobacter Res 2019;20:103-111, with permission from the Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research.[60]

(3) 병리 소견

H. pylori 음성인 인환세포암은 H. pylori 감염성 인환세포암에 비해서 크기가 작고 염증세포 침윤이 적다[22]. 조기 위암일 경우, 인환세포암임에도 불구하고 분화형(differentiated-type) 위암으로 진단되기 쉬운 이유는 다음과 같다. 분화형 위암과 미분화형(undifferentiated-type) 위암은 1960년대부터 사용되는 일본 특유의 병리진단명으로 분화형 위암은 선관 구조가 보존되어 있으면서 암세포가 빽빽하게 보일 때 진단한다[23]. 반면에 미분화형 위암은 선관 구조가 부실하고 암세포가 흐트러져 있을 때 진단한다. 선관의 손상도로 판단할 때, 분화형 위암은 로렌 분류(Lauren’s classification)상 장형(intestinal-type) 위암에 해당하며 미분화형 위암은 위축이나 장상피화생이 없는 고유점막에서 발생한 미만형(diffuse-type) 위암에 해당한다[24]. 하지만 형질의 발현도로 판단할 때, 일본에서 충실형 저분화도 선암(por1)이나 인환세포암(sig)으로 진단되는 조기 위암은 장형 위암이나 중간형 위암에 해당하는 경우가 많다[25]. 비충실형 저분화도 선암(por2)과 달리 por1이나 sig로 구성된 조기 위암은 미만형 위암보다 장형 위암에 가깝기 때문이다.

위와 같은 이유로 세계보건기구(World Health organization, WHO) 기준 상의 인환세포암과 저분화도(poorly differentiated) 선암을 미분화형 위암과 동일하게 취급하거나 고분화도(well differentiated)와 중분화도(moderately differentiated) 선암을 분화형 위암과 동일하게 취급하는 것은 위험하다. 이러한 혼선을 없애기 위해서는 내시경 조직검사로 위암이 진단될 경우, 병리 결과지에 로렌 분류가 추가되어야 한다. 또한, 로렌 혼합형일 경우에는 장형 우세형인지 미만형 우세형인지 기술되어야 한다. 위내시경 조직검사 결과만으로도 이분법으로 구분할 수 있어야 치료지침서도 제대로 활용할 수 있다.

(4) 치료 및 예후

한국이나 일본에서 진단되는 작은 인환세포암은 내시경 점막하 박리술만으로도 완전절제가 되며 예후가 양호하다[26]. 조기 위암일 때 절제하지 않으면 진행성 위암이 되어 예후가 불량하므로 가능한 빨리 절제해야 한다.

2) 위저선형 선암

정식 명칭은 주세포 우세형의 위저선의 선암(chief cell-predominant type, gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland)으로 2019년에 개정된 WHO 분류에 희귀한 위암으로 추가되었다[27]. 주로 기저부에 위축이 적은 고령자에서 진단되며 주세포 증식으로 인해 혈청 PG I 수치가 상승한다[28].

(1) 원인

위저선 용종의 위험인자는 장기간의 양성자펌프억제제(proton pump inhibitor, PPI) 복용으로, 세포분화이상이 발생하면 위저선형 선암으로 진행한다[29]. 위저선 용종이 진단된 196명의 환자 중 87명이 PPI를 복용하고 있었다는 보고도 있으며, PPI 복용으로 인한 위저선형 선암은 Ki 67 양성률이 높고 위저선이 확장되며 위선와(gastric foveola) 과형성과 벽세포(parietal cell) 돌출이 두드러진다[30].

PPI 복용과 무관한 위저선형 선암의 원인으로는 Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway의 활성화와 guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha stimulating complex (GNAS) 이상이 있다[31]. 우성유전 질환인 위선암과 근위부의 위용종증(gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach)에서도 위저선형 선암이 발생할 수 있다[32].

(2) 내시경 소견

위저선 용종과 감별하기 어려우므로 5 mm를 초과하는 위저선 용종이 보이면 위저선형 선암인지 조직검사로 확인한다[33]. Biopsy-on-biopsy 기법을 사용하여 상피하 조직을 채취해야 진단할 수 있다. 백색의 투명한 상피하 종양으로 관찰되며 EGC IIa나 EGC IIa+I처럼 보인다[34]. 표면이 정상 상피로 덮혀 있어서 암의 경계가 불명확한 것이 특징이다. 상피하 종양의 표면에는 혈관상과 위선 개구부가 관찰되며 초음파 내시경에서는 깊은 점막층이나 점막하층에서 저에코 병변이 관찰된다[35]. 점막하층을 침범할 수 있으나 근육층 이상을 침범하는 경우는 드물다[36]. 여러 개가 동시다발적으로 발생하는 경우도 있다[37].

(3) 병리 소견

위저선에서 발생한 분화도가 좋은 종양으로, 점액경부세포(mucous neck cell)나 유문선에서 분화된 MUC6, 주세포에서 분화된 PG I, runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3)에서 면역염색 양성 소견을 보이며 벽세포에서 분화된 H+/K+-adenosine triphosphate (ATP)ase와 platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA-α) 염색에서도 양성 소견을 보인다[38]. MUC5AC나 MUC6 중 하나라도 10% 이상에서 양성 소견을 보이면 위형 뮤신 발현형(gastric mucin phenotype)으로 진단되므로[39], MUC6 양성인 위저선형 선암은 위형 뮤신 발현형으로 분류된다. 한편, MUC2나 cluster of differentiation 10 (CD10) 중 하나라도 10% 이상에서 양성 소견을 보이면 장형 뮤신 발현형 (intestinal mucin phenotype)으로 진단된다.

드물지만 침습적인 경우, 나이나 성별과 무관하게 2 cm 이상으로 커지면서 CD10이나 caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) 면역염색에서도 양성 소견을 보여서 혼합형 뮤신 발현형으로 진단된다[40]. Kirsten rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog (KRAS)나 GNAS 유전자 변이가 있는 경우에는 1,000 μm 이상의 점막하층 침범이나 림프혈관 침윤(lymphovascular invasion)이 관찰될 정도로 침습적이다[41].

(4) 감별진단

위저선형 선암은 H. pylori 과거 감염자, 자가면역성 위염 환자, 가족성 대장선종증(familial adenomatous polyposis, FAP) 환자에서도 진단된다. 과거 감염자의 경우, 위저선의 수가 적고 선와 상피층이 얇기 때문에 확장된 나뭇가지 모양의 미세혈관들이 더욱 선명하게 투영된다[42]. FAP 환자의 경우, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) 유전자 변이로 감별한다[43].

자가면역성 위염 환자는 과형성 용종의 위암화와 선와상피세포 증식으로 인해 위암이 발생한다[44]. 자가면역성 위염에 의한 위암은 현 감염자나 과거 감염자에서도 발생하며[45], 위축이 진행된 감염자일수록 암이 호발한다[46]. H. pylori 미감염자와 감별할 수 있는 자가면역성 위염 환자들의 특징은 다음과 같다[47]. 첫째, 위내시경 검사 시 기저부와 상부 체부에서 저명한 위축을 보이지만 전정부에서는 위축이 관찰되지 않는다. 둘째, 항위벽세포항체(anti-gastric parietal cell antibody)나 항내인성인자항체(anti-intrinsic factor antibody)가 양성으로 보고된다. 셋째, 혈청 PG I 수치가 10 ng/mL 미만으로 매우 낮다. 넷째, 공복 시 혈청 가스트린 수치가 700 pg/mL를 초과한다. 다섯째, 선암보다 유암종(신경내분비세포 종양)의 발생률이 더 높으며 악성 빈혈, I형 당뇨, 갑상선염, 전신 홍반 루푸스, 피부근염, IgG4 연관성 질환, 원발 담즙성 간경변, Addison병 등 다른 자가면역 질환이 흔히 동반된다[48].

3) 초고분화도 선암

저이형성증의 분화형 위암으로도 불리며 일본 밖에서는 초고분화도 선암이 아닌 상피층에 국한된 이형성증이나 선종으로 진단된다[51]. 지금까지 보고된 증례는 대부분이 고령층의 일본인이며 국내에서는 47세 한국인 남성에서 진단된 증례보고가 있다[52].

(1) 원인

위저선의 이형성증은 통일된 진단기준이 없어서 위장관을 전공하는 병리전문의들 간에도 진단 일치도가 낮다는 사실을 고려할 때[53], WHO 진단기준으로는 이형성증이나 선종으로 진단되는 병변이 일본에서는 초고분화도 선암으로 진단되는 것으로 추정된다. 일본에서는 점막근판의 침윤 여부와 무관하게 핵의 모양으로 암을 진단하기 때문이다[54].

(2) 내시경 소견

기저부, 분문부 주변, 체부 상부나 중부의 대만측에서 진단된다[55]. 대부분 경계가 명확한 흰색의 EGC IIa형으로 관찰되지만(Fig. 2), 일부는 붉은 색의 EGC I형으로 관찰되어 산딸기처럼 보인다(Fig. 3) [56]. 여러 개의 병변이 동시에 발생할 수 있으며 선종과 감별하기가 어렵다[57]. 따라서 측방형 종양 모양의 결절형 결집, 융모상이나 유두상 모양의 융기, 표면이 울퉁불퉁한 융기, 중앙 함몰이 있는 납작한 융기 등 선종처럼 보이는 병변이 위의 근위부에서 관찰되면 의심해야 한다.

A whitish, flat-elevated, extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. (A) In the greater curvature of the mid-body, a 12 mm, whitish flat-elevated lesion is noticed. On the distal part of the cancer, small nodular changes are found with black spots. (B) On narrow band imaging (NBI) finding, clear demarcation lines are noticed at the cancer margins. There is a nodular part on the right side of the cancer. (C) Upon magnifying endoscopy with NBI, irregular microvascular pattern is noticed in the nodular part of the cancer. (D) In the non-nodular part of the cancer, regular microvascular and microsurface patterns are noticed on magnifying NBI finding. (E) On H&E staining of the nodular part of the cancer, an extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with low-grade dysplasia is noticed. (F) The non-nodular part shows less dysplasia and more mucin than those in the nodular part (H&E staining). Adapted from the article of Ueyama et al. Jpn J Helicobacter Res 2019;20:103-111, with permission from the Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research.[60]

A raspberry-like, extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. (A) An 8 mm, hyperemic, elevated lesion is noticed in the greater curvature side of the mid-body. (B) On narrow band imaging finding, thickened foveolar epithelial cells are noticed with discrete demarcation lines. (C) On H&E staining, an extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma is noticed with low-grade dysplasia. Adapted from the article of Ueyama et al. Jpn J Helicobacter Res 2019;20:103-111, with permission from the Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research.[60]

(3) 병리 소견

대부분은 위형 뮤신 발현형으로 분류되며 위선와세포에서 분화된 MUC5AC와 유문선이나 점액경부세포에서 분화된 MUC6 면역염색에 양성 소견을 보인다[58]. 일부는 술잔세포(goblet cell)에서 분화된 MUC2와 장상피화생의 솔가장자리(brush border)에서 분화된 CD10 면역염색까지 양성 소견을 보여 혼합형 뮤신 발현형으로 진단된다.

(4) 감별 진단

위저선형 선암처럼 선와상피세포의 분화를 보이지만 초고분화도 선암은 PG I과 H+/K+-ATPase 면역염색에서 음성 소견을 보이므로 감별할 수 있다[59]. 또한, PG I 양성 소견을 보이는 위식도 접합부의 분문부암과도 감별할 수 있다.

4) 고분화도 유문선암

유문선 선종(pyloric gland adenoma)이 일본과 독일의 독특한 병리진단기준에 인해 유문선암으로 진단된 것으로, 고령의 여성에서 흔하며 자가면역성 위염과 동반되기도 한다[62].

(1) 원인

유문선에서 발생한 선종의 20~30%는 adenoma-carcinoma sequence를 통해서 선암으로 진행한다[63]. 위저선의 가성 유문선 화생성 변화(pseudo-pyloric metaplasia)로 인해서 발생하므로, 전정부가 아닌 위체부(64%)와 분문부(8%)에서 발견된다는 보고도 있다[64]. 알려진 유전자 이상으로는 17pq, 20q의 증폭과 4q, 5q, 6q의 결손 등이 있다[65].

(2) 내시경 소견

주변 위점막과 같은 색을 지녀서 경계가 불명확한 EGC IIa형으로 관찰된다[66].

(3) 병리 소견

MUC6와 MUC5A 면역염색에서 강한 양성 소견을 보이며 일부는 chromogranin A에서도 양성 소견을 보인다[67].

(4) 감별진단

FAP 환자에서 관찰되는 유문선의 선종과 유사하게 보이지만, 고분화도 유문선암은 GNAS, KRAS, APC 유전자 변이가 없으므로 감별할 수 있다[68].

(5) 치료 및 예후

예후가 양호해서 선종에 준해서 치료한다[69].

2. H. pylori 음성 위암의 진단기준

H. pylori 감염력이 없는 위를 진단하는 통일된 기준은 없으나 제균 치료를 받은 적이 없고 침습적인 검사와 비침습적인 검사 모두에서 H. pylori 음성 소견을 보이면 미감염자일 가능성이 있다(Table 2). H. pylori 감염자가 많은 지역일수록 과거 감염자를 배제하기 위해 다음 항목들을 모두 확인하는 것이 바람직하다.

1) H. pylori 감염으로 진단받은 적이 없다

의도치 않게 제균되거나 자가소멸된 경우가 있기 때문에 제균 치료의 과거력 이외에 H. pylori 감염으로 진단받은 적이 있는지를 확인한다. 과거 감염자 중에는 검사 소견까지 모두 정상으로 회복되어 문진만으로 감염력을 확인할 수 있는 경우가 있기 때문이다[70].

2) 침습적인 검사와 비침습적인 검사에서 모두 H. pylori 음성 소견을 보인다

H. pylori 균은 위 안에서 균일하게 분포하지 않기에 침습적인 검사만으로는 5명 중 1명의 감염자를 놓칠 수 있다[71]. 반대로 H. pylori가 아닌 헬리코박터(non-H. pylori Helicobacter)나 캠필로박터(Campylobacter) 균이 병리 소견에서 양성으로 보고되어 H. pylori 감염으로 오진되기도 한다[72]. 따라서 비침습적인 검사와 배경 위점막의 내시경 소견을 함께 참조해야 H. pylori 감염 상태를 보다 정확하게 진단할 수 있다. 혈청 항 H. pylori 항체 검사 시에는 IgG 수치를 반드시 확인해야 하며 IgM이나 IgA는 정확도가 낮아서 사용하지 않는다[73]. 요소호기 검사나 단클론성(monoclonal) 대변항원 검사는 정확도가 높아서 제균 치료 성공 여부를 확인할 때도 유용하다[74].

3) 조직검사에서 장상피화생이나 위축이 관찰되지 않고 중등도 이상의 염증세포 침윤이 없다

한국인에서 위축성 위염이나 장상피화생이 있는 위암 환자를 과거 감염자로 분류하면 H. pylori 음성 위암의 유병률이 13.9%에서 4.0%로 감소한다[75]. 일본에서 미감염자의 조직검사 소견을 시드니 체계분류 상 호중구 침윤 0점, 단핵구 침윤 0~1점, 위축 0점, 장상피화생 0점인 경우로 국한한 결과, H. pylori 음성 위암의 유병률이 1% 미만으로 낮았다[76]. H. pylori 이외의 다른 균이 2점 이상의 염증세포 침윤이나 만성 위염을 유발하는 경우는 드물기에 호중구 침윤이나 중등도 이상의 단핵구 침윤이 보이면 H. pylori 감염을 의심해야 한다[77].

4) 위점막에서 균일한 혈관상이 관찰되며 H. pylori 감염을 시사하는 소견이 없다

과거 감염자에서 관찰되는 대표적인 소견 세 가지는 황색종, 화생성 위염, 체부까지 진행한 위축성 위염이다[78]. 하나라도 관찰되면 H. pylori 과거 감염을 진단할 수 있으며, 기저부나 체부 상부에서 다발성 혈성 반점(미만성 발적)까지 관찰된다면 현감염을 의심해야 한다. 배경 위점막의 내시경 소견으로 과거 감염자를 제외한 뒤 미감염자만을 포함시킬 경우, 일본에서 진단된 분화형 위암 중 H. pylori 음성 위암의 유병률은 0.42%[79]. 미분화형 위암은 0.66%로 낮아진다[80]. 반대로 위점막의 내시경 소견을 확인하지 않고 혈청학적 위축으로만 과거 감염자를 배제할 경우, H. pylori 음성 위암의 유병률은 10.6%까지 상승하며 인환세포암의 비율이 60~70%까지 높아진다[81].

5) 혈청 PG 검사에서 위축(PG I ≤70 ng/mL & PG I/II ≤3.0)이 없다

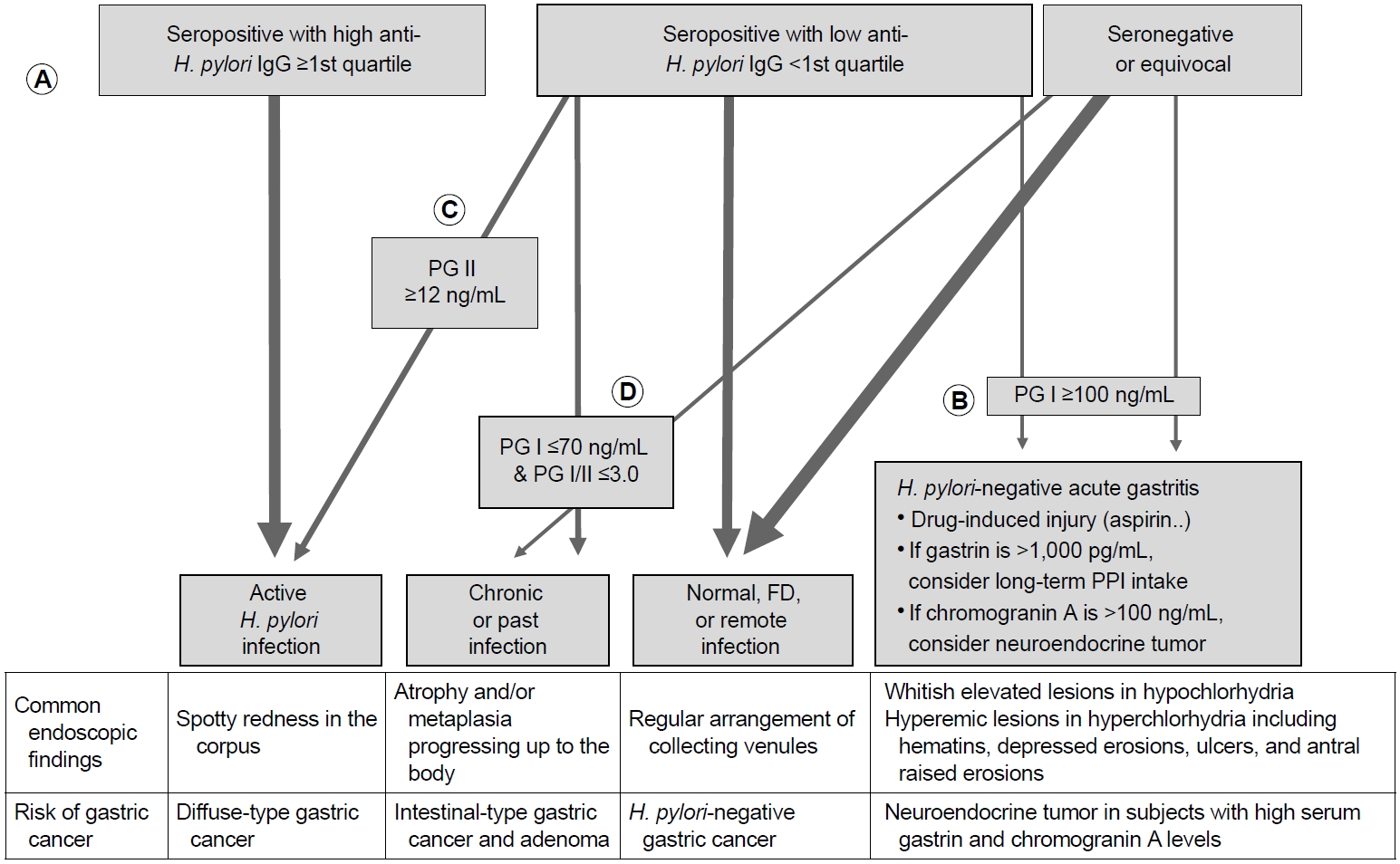

문진 및 H. pylori 검사, 위내시경 소견으로 미감염자로 분류된 사람들에게 혈청 PG 검사를 추가하면 26.7%에서 혈청학적 위축이 진단되어 과거 감염자로 분류되기도 한다[82]. 단, 최근에 제균 치료를 받았거나 신부전이 있거나 위절제술을 받은 환자에서는 PG 수치가 부정확하므로 PG 검사를 권하지 않는다. H. pylori 감염 상태를 보다 정확하게 판단하기 위해서 자체적으로 만들어서 사용하고 있는 알고리즘은 Fig. 4와 같다.

Personal recommendation on interpreting the serum assay findings. (A) After excluding patients with recent H. pylori eradication, post-gastrectomy, or renal failure, check whether the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer is equal or greater than the 1st quartile among the seropositive test findings. For example, when using the Chorus H. pylori IgG assay, which shows the titers between <5 AU/mL and >200 AU/mL, most of the subjects showing ≥60.0 AU/mL have an ongoing H. pylori infection. (B) In symptomatic patients, check whether PG I level is increased owing to H. pylori-negative gastritis. (C) In asymptomatic subjects, check PG II level first before checking PG I level. If PG II is ≥12.0 AU/mL in seropositive subjects in the 1st quartile (between ≥12.0 AU/mL and <60.0 AU/mL), most have ongoing H. pylori infection. (D) Lastly, check whether there is serologic atrophy. If PG I is ≤70 ng/mL and PG I/II is ≤3.0, subjects should be classified as having either chronic or past H. pylori infection. Remnants are non-infected subjects including some symptomatic FD patients and few with remote eradication history. H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; PG, pepsinogen; FD, functional dyspepsia; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

(1) 혈청 항 H. pylori IgG 수치의 활용

혈청 항H. pylori IgG 수치는 균의 양과 비례해서 증가하므로[83], IgG 수치가 양성 기준치의 상위 75%에 속한다면 대부분이 현감염자이지만 하위 25%에 속한다면 위양성인 경우가 있다. 예를 들면, 한국인에서 민감도와 특이도가 100%와 75.4%인 Chorus H. pylori IgG (DIESSE Diagnostica Senese, Siena, Italy)로 검사할 경우[84], 혈청 항 H. pylori IgG ≥60.0 AU/mL부터 최고치인 >200 AU/mL는 감염을 시사하지만, ≥12 AU/mL에서 <60.0 AU/mL일 경우에는 다음과 같은 확인과정이 추가로 필요하다.

(2) 혈청 PG I과 PG II 수치의 활용

혈청 항 H. pylori IgG 수치가 양성 기준치의 하위 25%에 속할 경우, 환자가 증상이 있다면 PG I 수치를 먼저 확인해서 H. pylori 감염과 무관한 급성 위염(H. pylori-negative acute gastritis)을 감별한 뒤[85], PG II 수치를 확인한다. 만약 증상이 없다면 PG II 수치로 감염자를 먼저 배제한 뒤, PG I 수치를 확인한다. 위 세 가지(혈청 항 H. pylori IgG, PG I, PG II) 수치로도 분류되지 않은 경우, PG I ≤70 ng/mL & PG I/II ≤3.0에 해당하는지 확인해서 만성과 과거 감염자로 분류한다. 지난 10년간의 경험에 의하면 혈청학적 위축이 있는 경우, 10명 중 9명은 현감염자였으며 과거 감염자는 약 10%에 불과하였다. 한국인 조기 위암 환자에서조차 제균 치료 성공 시 PG I/II 수치가 5년 안에 정상으로 회복되므로[86], 혈청학적 위축이 지속되는 과거 감염자가 적기 때문이다. 드물게 혈청학적 위축을 제외한 Table 2의 모든 진단기준에 부합하여 혈청학적 위축이 위양성 소견으로 의심되는 경우가 있는데, 대부분이 40세 미만의 젊은 연령대였다.

결 론

H. pylori 감염률이 감소할수록 H. pylori 음성 위암의 발생률은 증가할 것이다. H. pylori 음성 위암을 놓치지 않기 위해서는 유문선과 위저선의 경계부에서 발생하는 인환세포암, 위저선 용종처럼 보이는 위저선형 선암, 선종처럼 보이는 초고분화도 선암과 고분화도 유문선암의 특징을 숙지하는 것이 좋다. H. pylori 미감염자를 진단할 때는 본인도 모르는 사이에 전염되었던 과거 감염을 배제하기 위해서 엄격한 기준을 사용해야 한다. H. pylori 감염으로 진단받은 적이 없고, 침습적인 검사와 비침습적인 검사에서 모두 감염이 없어야 하며, 위점막에서 균일한 혈관상이 관찰되어야 한다. 아울러 황색종이나 화생성 위염, 위각을 넘어 체부까지 진행된 위축성 위염이 관찰되지 않고, 혈청학적 위축(PG I ≤70 ng/mL & PG I/II ≤3.0)도 없어야 한다. 조직검사 소견에서는 장상피화생이나 위축, 호중구 침윤 또는 중등도 이상의 단핵구 침윤이 없어야 한다. 안타깝게도 현재 우리나라에는 H. pylori 음성 위암을 진단하는 과정에 큰 걸림돌이 두 가지가 있다. 첫째, 혈청 검사 소견과 배경 위점막의 내시경 소견을 판독하는 방법에 대한 교육이 부족하여 위내시경 검사를 매일 시행하는 전문의들조차 H. pylori 감염 상태를 감별하지 못하는 경우가 많다. 둘째, 위내시경 조직검사에서 위암이 진단되어도 병리 결과지에 로렌 분류에 대한 언급이 없고, 로렌 분류가 혼합형일 때는 장형 우세형인지 미만형 우세형인지에 대한 기술이 없다. 이를 간과하면 안 되는 이유는 인환세포암의 병리 소견 부분에 자세히 기술하였다. 보다 정확하고 효율적인 H. pylori 음성 위암의 진단과 치료를 위해, 위암 검진을 시행하는 의사들의 적극적인 지식습득과 능력 있는 국내병리의사들의 활약을 기대해본다.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.