|

|

- Search

| Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res > Volume 24(1); 2024 > Article |

|

Abstract

Foreign body ingestion, a common emergency encountered in clinical practice, is a potentially serious condition. Most foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract pass spontaneously. However, objects that are relatively long or large may lodge in the upper gastrointestinal tract, potentially causing perforation, bleeding, and obstruction. This literature review summarizes the natural history and clinical aspects of these types of foreign bodies in adults as well as the various methods for their removal. Endoscopic removal is a relatively safe and effective procedure for removing these types of foreign bodies. The development of endoscopic techniques and devices has resulted in their widespread use, with good results, as the primary treatment.

The types of foreign materials entering the digestive tract can vary depending on time and the patient’s culture. Small foreign objects generally pass through the gastrointestinal tract without any complications, such as retention or bleeding, in the digestive tract. However, in 10%–20% of patients, endoscopic removal of foreign bodies (FBs) may be necessary because the objects cannot pass through the normally narrow or abnormally narrowed areas of the upper gastrointestinal tract; in fewer than 1% of cases, surgical treatment may be necessary [1-3]. This review summarizes the natural history and clinical aspects of FBs in the upper gastrointestinal tracts of adults and also surveys the various methods for the removal of these objects.

FBs enter the upper gastrointestinal tract in three different ways. FBs, such as coins, metal particles, fish bones, nails, and needles, may be directly swallowed. Second, food particles and other substances, such as bezoars, may form a mass once in the stomach. Finally, fistulas may arise as a result of surgery, wounds, and congenital or acquired defects in other parts of the body that allow FBs to enter. Among these possible routes, the most common route of entry for a FB is the swallowing of an object. In adults, food-related FBs are generally observed in patients with organic or functional lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, older adults, and in otherwise healthy individuals. Food-related FBs mainly include food ingredients, such as pieces of meat, fish or other types of bones, and fruit seeds. Other types of swallowed FBs may include a diverse array of accidentally swallowed items, including medicine packaging, toothbrushes, bottle caps, and spoons. Besides accidentally swallowed objects, alcoholics, people with mental illnesses, and prisoners seeking secondary gain may intentionally swallow foreign objects. Recently, upper gastrointestinal FBs increasingly include disc batteries pressed through their packages, dental prostheses, or dentures [4]; sharp and dangerous FBs have consistently been reported as swallowed objects in the psychiatric population. In healthy individuals, food boluses pass spontaneously, whereas in the presence of upper gastrointestinal tract diseases (e.g., cancer and strictures), the risk of food bolus impaction are increased. Therefore, a diagnostic workup to determine potential underlying diseases is recommended in patients with food bolus impaction [5].

Clinical symptoms of upper gastrointestinal FBs can vary depending on the size, type, and location of the foreign object; the degree of mucosal irritation; and the presence or absence of complications, including dysphagia, mild abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, fever, tachycardia, and weight loss. In most cases, no unusual symptoms occur in the early stages, except in cases where the FB is caught in the upper esophagus or oropharynx and causes direct irritation or completely blocks the lumen [6].In cases where an FB is intentionally swallowed, it is often not discovered until specific symptoms or complications, such as vomiting or refusing to eat, occur. Areas where FBs often lodge are normally narrow, such as at the upper or lower esophageal sphincter or areas that bend at a sharp angle, such as the duodenum. The piriform sinus is the most common area in which an FB lodges following passage through the mouth and oropharynx. In such cases, the patient experiences considerable discomfort. Approximately 50%–80% of esophageal FBs are caught in the upper esophagus or at the upper esophageal sphincter; the rest lodge in the chest and distal esophagus. The parts of the esophagus that can be narrowed, even if normal, include the cricopharyngeal muscle (the area where the aortic arch passes), near the left main bronchus, and near the lower esophageal sphincter. Even if FBs pass through the esophagus, long objects, such as nails or pins, may not pass through the bulb and curve of the duodenum. Therefore, if a long object is detected in the stomach, it should be removed endoscopically before it passes through the pylorus. In addition, objects that are dangerous (e.g., batteries), sharp, >2.5 cm in diameter, long, cause complete obstruction of the esophagus, remain in the stomach for >48–72 h, and those causing difficulty breathing should be removed immediately [7,8].

For patients presenting in the hospital with a history of FB ingestion, identification and radiographic localization are the preferred initial steps [9].If an FB is suspected to be stuck in the esophagus, upper esophageal sphincter, neck (anterior/posterior and lateral), or chest, radiography should be performed. If an FB in the lower esophagus or abdomen is suspected, abdominal radiography is necessary [9-11]. In many cases, localization of the FB can be determined using imaging. However, radiolucent substances, such as some food materials, often do not appear on general radiographs. If subcutaneous air is observed during simple imaging, complications are suspected, or symptoms and fever persist over a long period, chest and abdominal computed tomography should be considered. Although routine radiological examinations may not reveal small bones, thin metals, or plastic objects, failure to radiographically detect an object does not rule out its presence. Therefore, in patients with clinical features typical of suspected FB ingestion, an endoscopic evaluation must be performed even if the radiographic findings are normal [12]. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) classifies endoscopic interventions into three groups (emergent, urgent, and nonurgent), according to the situational severity [11], and recommends emergent endoscopic intervention in cases of high-grade esophageal obstruction and ingestion of disk batteries or long-pointed objects (Table 1) [11,13]. A recent study described a scoring system for predicting the need for emergent endoscopy due to esophageal FBs. In this study, a period of less than 6 h since ingestion, absence of any meal after ingestion, dysphagia, odynophagia, and drooling were introduced as five different variables independently associated with endoscopic confirmation of FBs and food bolus impaction in the esophagus. A decisionto-scope scoring system using these variables was reported; the optimal cutoff score for identifying low-risk patients was a score of less than or equal to five (sensitivity, 85.0%; specificity, 94.7%) [14]. Loh et al. [15] suggested that the risk of developing major complications is 14 times higher for FBs impacted for more than 1 d than in FBs impacted for <24 h. Wu et al. [16] reported that patients with delayed (>24 h) endoscopic intervention may develop additional symptoms, including dysphagia and esophageal ulcers, but concluded that serious complications (e.g., esophageal perforation and bleeding) were not correlated with impaction duration. In a multivariate analysis, another retrospective study identified the risk factors for endoscopic complications and failure as pointed objects (hazard ratio [HR]=2.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07–5.72; p=0.034) and a >12 h duration of impaction (HR=2.42; 95% CI, 1.12–5.25; p=0.025) [12]. A recent retrospective study conducted in South Korea reported that early recognition and timely endoscopic removal of ingested FBs, particularly from older adults and from those who had ingested sharp FBs, may improve clinical outcomes [17]. Therefore, based on current evidence, the ASGE and the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommend therapeutic endoscopy for all cases of esophageal FBs within 24 h after ingestion, especially in cases involving pointed objects ingested within the previous 6 h [11,18].

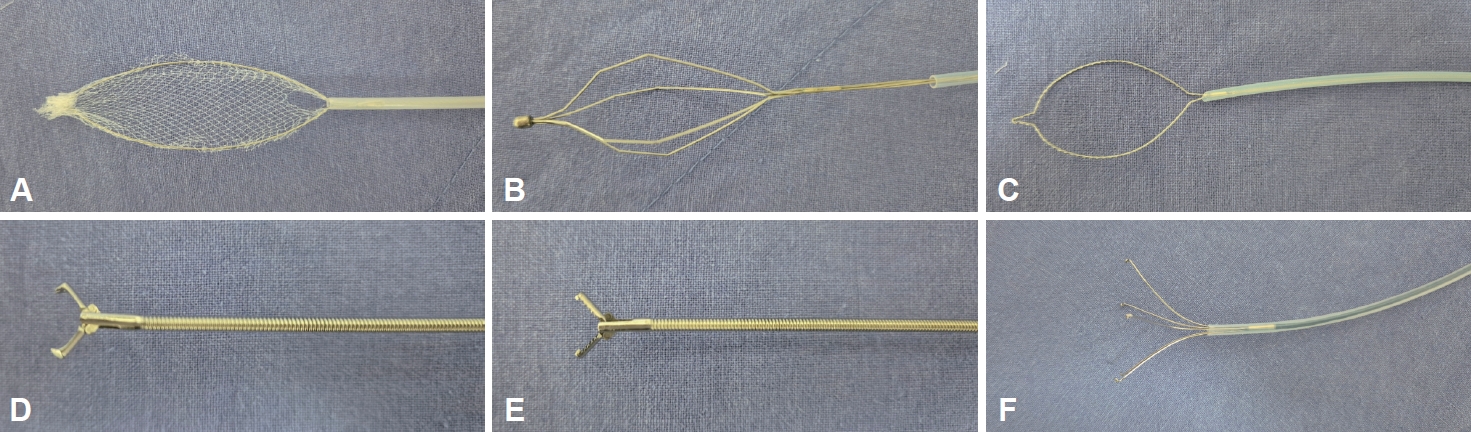

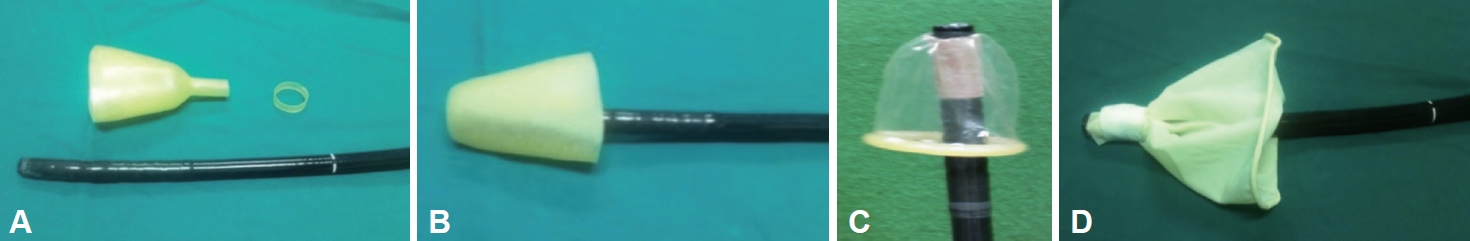

As the number of cases of sharp and dangerous objects being swallowed increases, the use of an overtube or protective hood is recommended to minimize mucosal damage during endoscopic removal. Endoscopic removal tools include net catheters, basket catheters, snares, rat tooth forceps, alligator jaw forceps, and five-pronged grabbers (Fig. 1). In animal experiments involving the endoscopic removal of FBs (metal tacks, button disc batteries, and wooden toothpicks) [19], only the net and basket successfully retrieved button disc batteries, with the net having superior success compared with the basket (100% vs. 27%; Fisher’s p<0.025). All devices were equally successful in retrieving the tack (82%–100%, p=no significance). The snare was significantly faster than the net (p<0.05). The net was in-capable of retrieving the toothpick, and the other devices were equally successful (91%–100%). However, no guidelines specify the use of specific instruments during the endoscopic removal of FBs from the digestive tract. Therefore, the choice of removal instrument should be determined based on its availability at the institution and the proficiency of the endoscopist with the available instruments. FBs that are small and easy to grasp can be removed easily using biopsy forceps. Also, biopsy forceps can be used to remove extremely thin and short fish spines. In the case of relatively large FBs, the use of biopsy forceps is not recommended because the object may be dropped. Alligator forceps have gripping surfaces shaped like crocodile jaws or saw blades. Therefore, alligator forceps are better tools for removing thin and hard FBs, such as small coins and fish bones, lodged in the esophagus. The snare catheter is optimized to remove long, hard FBs. Therefore, a snare catheter is best for removing long FBs, including ballpoint pens, wires, toothbrushes, and hairpins. Notably, long FBs, such as ballpoint pens or toothbrushes, should be held at the very end of the object to minimize damage to the mucosal membrane during removal as this allows the FB to be positioned parallel to the lumen during removal. The tripod catheter compensates for the disadvantage of the snare having to approach the lesion from the side; the tripod catheter is able to approach and grasp the FB from the front. Therefore, pieces of meat and fruit seeds, which are difficult to grasp due to their usually being round and not hard, can easily be removed using a tripod catheter. The net catheter is an FB removal device that is more suitable for removing round, rather than flat, objects. Because the net covers the entire FB, the chance of the FB being lost during removal is low. Moreover, when there are several small FBs, they can be removed simultaneously using a net; the net also acts as a protective shield to cover the entire surface of the FB, such as a flat fish bone. The net also reduces mucosal damage by covering the sharp margins of flat FBs. Sharp FBs are difficult to remove using an endoscope and serious complications, such as bleeding and perforation, may occur. Therefore, in some cases, the use of accessories, such as overtubes (Fig. 2) and protector hoods, is advisable in some instances. In the absence of a protective hood, surgical gloves and condoms can be used (Fig. 3); however, they are more difficult to operate than hoods. The endoscope cap is an essential device for therapeutic en-doscopy. In the case of a small, sharply pointed FB, endoscope caps can prevent exposure of the sharp part of an FB in the absence of an overtube. Many FBs are caught in the upper esophageal sphincter. In such cases, the use of a cap is essential because the view cannot be secured simply by injecting air (Fig. 4). In two recent meta-analyses of cap-assisted endoscopic removal of an esophageal food bolus and/or FB impaction, technical success and en bloc retrieval rates were significantly higher in the cap-assisted group than in the conventional group. Additionally, there was a trend toward lower procedure times in the cap-assisted group; the overall adverse events were comparable between the groups [20,21].

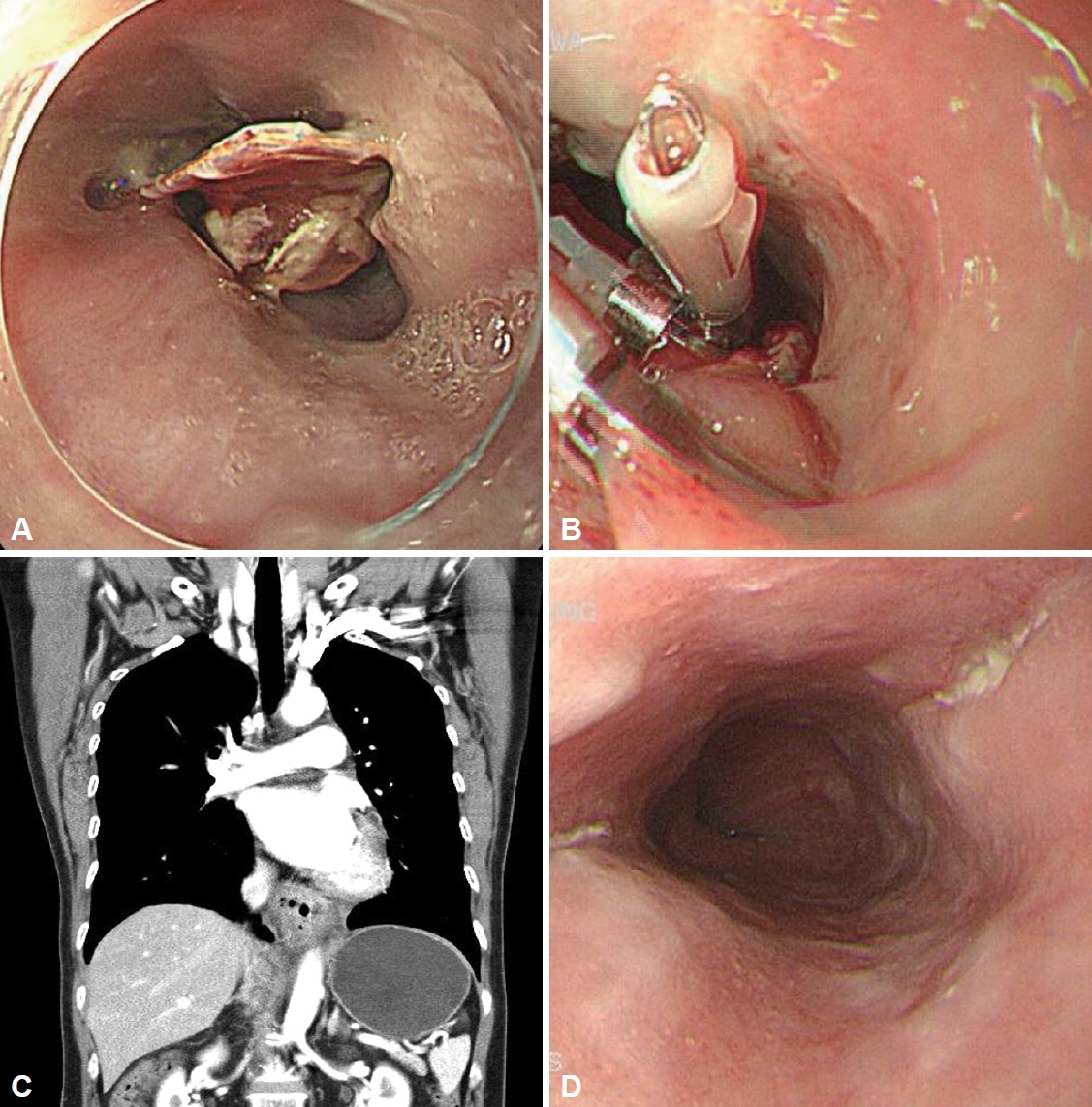

In rare cases, surgical treatment is necessary when serious complications related to FBs in the upper gastrointestinal tract occur or when endoscopic treatment fails or is not possible. The frequency of failure in the endoscopic removal of FBs varies from approximately 1.1% to 8.04% [5,12,17,22]. The surgical approach depends on the nature and location of the FB. For example, if a gastric FB is wider than 2 cm, longer than 10 cm, unlikely to pass through the pylorus without difficulty [23], or if esophageal FB impaction causes aspiration and asphyxia, emergency surgery is required. Delays of more than 12 h after FB ingestion, have been reported as factors causing failure of endoscopic removal of pointed objects and intentionally ingested objects [12,22]. The most serious complications result from esophageal perforations, including pneumomediastinum, mediastinitis, periesophageal abscess, aortoesophageal fistula (AEF), and tracheoesophageal fistula. Primary suturing can be considered for repairing perforations (Fig. 5) and drainage can be considered for abscesses around the esophagus or behind the pharynx. However, if complications are difficult to treat, surgery should be considered. AEF with a pseudoaneurysm caused by an esophageal FB is a rare but serious complication [4,24]. The most common site of an esophageal FB causing AEF is the thoracic esophagus at the level of the aortic arch. Once an AEF is diagnosed, timely open thoracic surgery is critical for successful treatment. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair is not only a bridging treatment for hemostasis but also the main treatment for AEF [4,24].

Endoscopy is the preferred method for FB removal, depending on the type, size, and shape of the FB as well as the patient’s physical condition. Endoscopic removal of FBs from the upper gastrointestinal tract is a relatively safe and effective procedure. With the development of endoscopic techniques and assistive devices, these procedures are often considered the primary treatment and have shown good results. Moreover, most FBs in the upper gastrointestinal tract can be endoscopically removed. Depending on its location and nature, an FB may cause perforation, obstruction, bleeding, or infection. Therefore, removal should be performed as soon as possible. Sharp FBs can damage the esophageal mucosa, esophageal-gastric junction, and upper esophageal sphincter mucosa during removal, leading to various complications such as bleeding and perforation. Therefore, various protective devices should be properly chosen and used during the removal of FBs.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Hee Seok Moon, a contributing editor of the Korean Journal of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article.

All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Fig. 1.

Equipment for removal of gastrointestinal tract foreign bodies. Net catheter (A), basket catheter (B), snare (C), rat tooth forceps (D), alligator jaw forceps (E), five-pronged grabber (F).

Fig. 2.

An esophageal fish bone foreign body. A: Endoscopy shows the fish bone embedded in the distal esophagus. B and C: The fish bone is being removed using alligator jaw forceps and an overtube. D: The removed foreign body is a fish bone approximately 4 cm in length.

Fig. 3.

Various accessories for reducing mucosal damage when removing sharp foreign bodies. Protector hood (A and B), condom (C), latex surgical glove (D).

Fig. 4.

Foreign body lodged in the epiglottic vallecula. A: Endoscopy shows a foreign body impacted in the right epiglottic vallecular area. B: The removed foreign body is a wooden toothpick approximately 3 cm in length.

Fig. 5.

Esophageal foreign body complications. A: Esophageal endoscopy shows a perforated esophageal ulcer caused by pressure through package. B: Endoscopic treatment of the perforation is performed using endoclips. C: Chest computed tomography reveals pneumomediastinum. D: The perforation site is improved in the follow-up endoscopy.

Table 1.

Timing of the endoscopic removal of foreign bodies

REFERENCES

1. Longstreth GF, Longstreth KJ, Yao JF. Esophageal food impaction: epidemiology and therapy. A retrospective, observational study. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:193–198.

2. Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;41:39–51.

3. Mosca S, Manes G, Martino R, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: report on a series of 414 adult patients. Endoscopy 2001;33:692–696.

4. Zhang R, Hao J, Liu H, Gao H, Liu C. Ingestion of a row of artificial dentures in an adult: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102:e35426.

5. Geng C, Li X, Luo R, Cai L, Lei X, Wang C. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a retrospective study of 1294 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol 2017;52:1286–1291.

6. Chun HR, Chun HJ, Keum B, et al. A case of esophageal foreign body induced by glue ingestion. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc 2005;30:24–27.

7. Shemesh E, Czerniak A, Hakerem D. Endoscopic removal of penetrating foreign bodies from the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc 1989;35:473–474.

8. Quinn PG, Connors PJ. The role of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in foreign body removal. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 1994;4:571–593.

9. Smith MT, Wong RK. Esophageal foreign bodies: types and techniques for removal. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2006;9:75–84.

11. Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:1085–1091.

12. Hong KH, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Chun SW, Kim HM, Cho JH. Risk factors for complications associated with upper gastrointestinal foreign bodies. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:8125–8131.

13. Bekkerman M, Sachdev AH, Andrade J, Twersky Y, Iqbal S. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract: a review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016;2016:8520767.

14. Macedo Silva V, Lima Capela T, Freitas M, et al. Decision-to-scope score: a novel tool with excellent accuracy in predicting foreign bodies in the esophagus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;38:970–975.

15. Loh KS, Tan LK, Smith JD, Yeoh KH, Dong F. Complications of foreign bodies in the esophagus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:613–616.

16. Wu WT, Chiu CT, Kuo CJ, et al. Endoscopic management of suspected esophageal foreign body in adults. Dis Esophagus 2011;24:131–137.

17. Yoo DR, Im CB, Jun BG, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic removal of foreign bodies from the upper gastrointestinal tract. BMC Gastroenterol 2021;21:385.

18. Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, et al. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy 2016;48:489–496.

19. Faigel DO, Stotland BR, Kochman ML, et al. Device choice and experience level in endoscopic foreign object retrieval: an in vivo study. Gastrointest Endosc 1997;45:490–492.

20. Ahmed Z, Arif SF, Ong SL, et al. Cap-assisted endoscopic esophageal foreign body removal is safe and efficacious compared to conventional methods. Dig Dis Sci 2023;68:1411–1425.

21. Mohan BP, Bapaye J, Hamaad Rahman S, et al. Cap-assisted endoscopic treatment of esophageal food bolus impaction and/or foreign body ingestion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol 2022;35:584–591.

22. Calini G, Ortolan N, Battistella C, Marino M, Bresadola V, Terrosu G. Endoscopic failure for foreign body ingestion and food bolus impaction in the upper gastrointestinal tract: an updated analysis in a European tertiary care hospital. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;35:962–967.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 1,263 View

- 20 Download

- Related articles in Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res

-

Non-Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding2024 March;24(1)

Gastrointestinal Tract Lymphoma2022 March;22(1)

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding with Cholecystoduodenal Fistula2022 March;22(1)

Infectious Diseases of the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract2019 March;19(1)

Neuroendocrine Tumor in Upper Gastrointestinal Tract2011 September;11(2)